This is the thirty-fourth entry of Russia’s Alien Nations: The Secret Identities of Post-Socialism, an ongoing feature on All the Russias, as well as the final entry of Chapter 1. It can also be found at russiasaliennations.org. You can also find all the previous entries here.

As a creature of the Internet, Vatnik does not exactly inspire hope. Social media and the blogosphere are an ideal cauldron for brewing a stew of negativity and bile. Look at poor Pepe the Frog, created by Matt Furie as an icon of whimsy and irony only to be hijacked by the alt-right and transformed into a kid-friendly, anthropomorphic analog to the swastika. But we should not forget the Internet’s numerous advantages: the rate of change and demand for novelty give most memes a limited shelf life (as long as those who take offense do not foolishly fall victim to the notorious Streisand Effect) . Moreover, the example of Pepe also reminds us that memes can evolve into unexpected forms. Not all of them have to be toxic.

I close out this chapter with one more meme that has come to serve as an icon of the post-Soviet Russian experience, a meme whose mild political undercurrents are no obstacle to its broad circulation and acceptance. The fact that this meme’s origins are not even Russian, and that it enjoys just as much popularity in Belarus and Ukraine, is not simply ironic, but thoroughly appropriate. Here we have a cultural model of particularity (underscoring something specific to the local environment) without isolationism, and the meme’s success in all three Slavic post-Soviet nations is a reminder of a shared cultural core that is free from any kind of Russian (post-) imperial hegemony. Known in Belarus as “Pochakun” and in Ukraine as “Pochekun”, it is most famous on the internet under its Russian name: Zhdun.

As a post-Soviet phenomenon, Zhdun’s origins could not be more unlikely. It began as a sculpture by the Dutch artist Margriet van Brevoort, who installed a work entitled “Homunculus loxodontus” at the Leiden University Medical Center in 2016. In an interview, she explained its origins to a Russian reporter:

I wanted to give it a scientific name, like a new species. Homunculus means 'little guy' in Latin, or 'artificially created human.' And Loxodontus is the scientific name for African elephant, referring to the snout. I was commissioned by 'Beelden in Leiden' to make something inspired by the LUMC, the medical center in Leiden, and I didn't want to create something about medicine or illness, but rather about the patients themselves. The way they just have to await their fate in the waiting rooms. About hoping for the best. […] I wanted it to be a kind of lovable companion, something or someone that gives comfort, but also makes you laugh. In this building, there is also a lot of medical and genetic research going on. So the way the sculpture looks is a bit of a joke towards this research. It's like a failed experiment or product of this research that is hoping and waiting to get better. Like a big, cute, partly human and huggable lump of flesh.

The story would have ended there, with a charming statue in front of a Dutch medical facility visited by a limited number of people. But in January 2017, a photograph of Homunculus Loxodontus found its way to the Russian Reddit clone Pikabu, Quickly acquiring its Russian, Belarusian, and Ukrainian nicknames, the meme spread so rapidly that in the following month, a member of the Ukrainian Verkhovna Rada (the parliament) brought a stuffed “Pochekun” figure with him to the parliamentary meeting hall and parked him in front of a microphone.

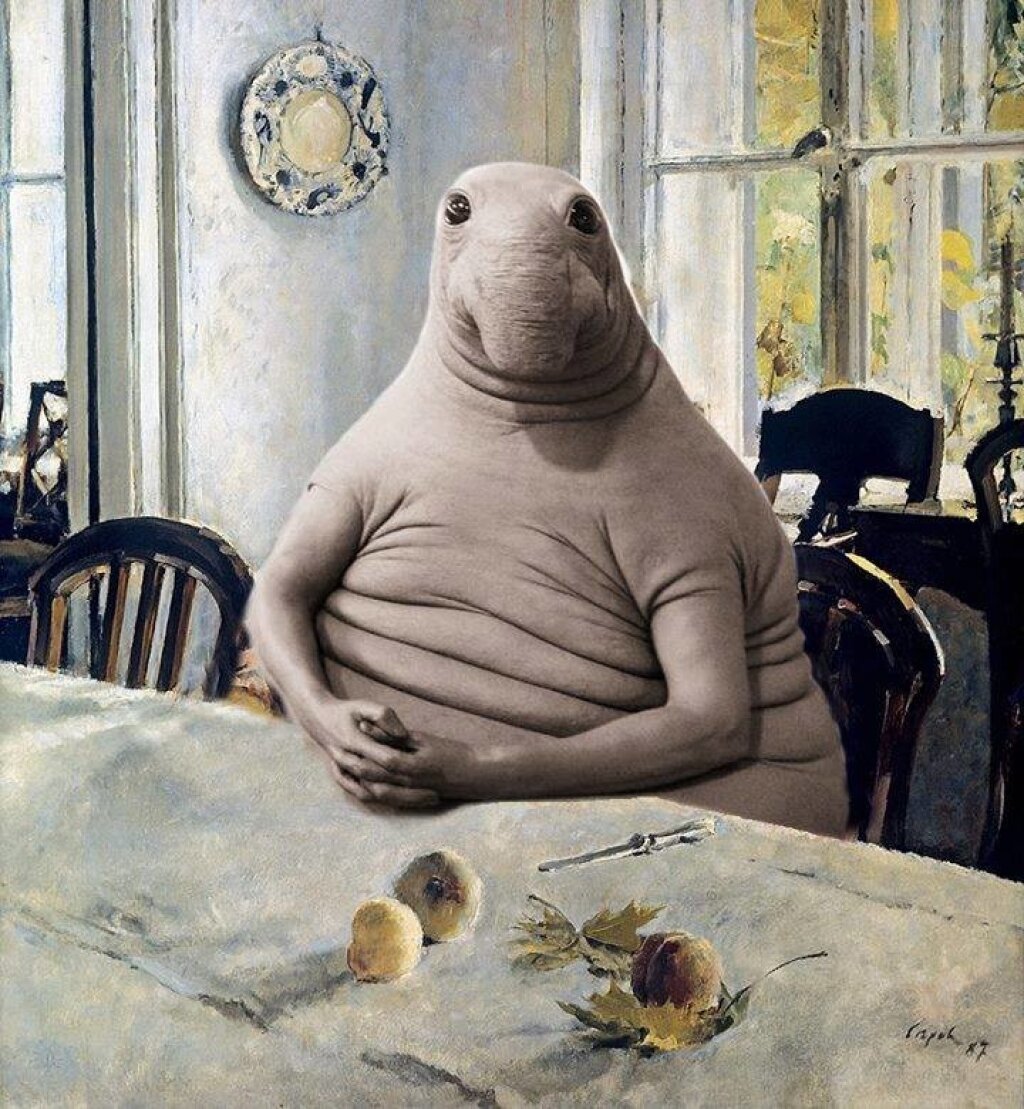

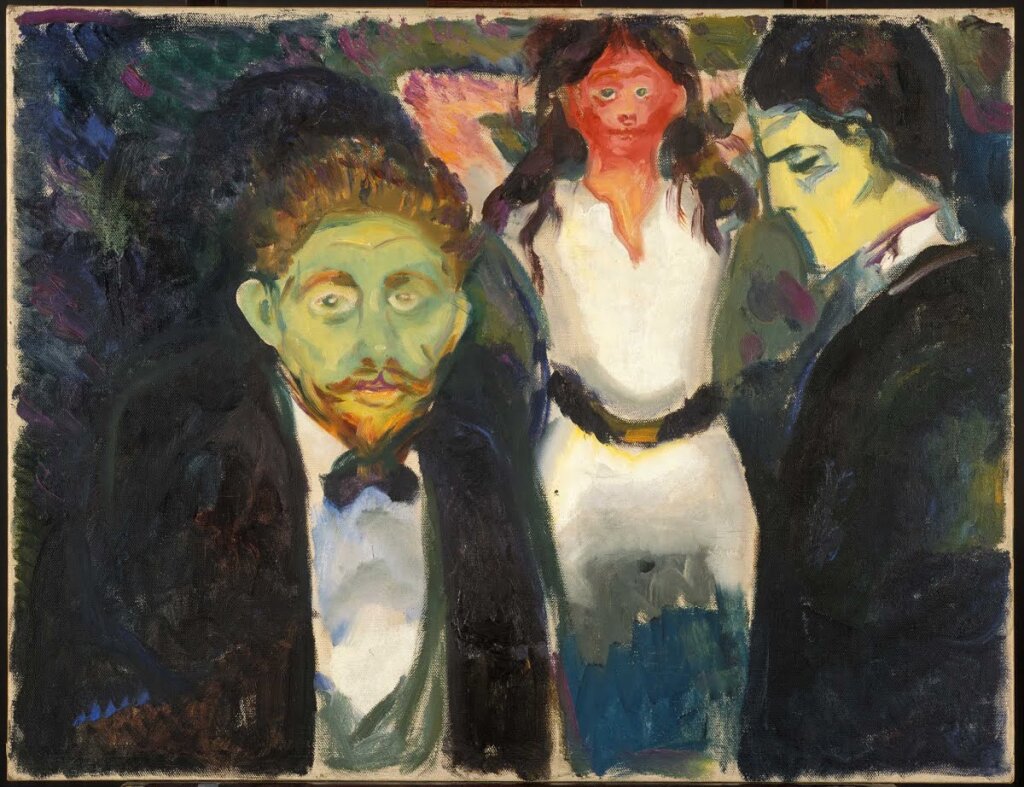

Why did Zhdun go viral? Why is his image photoshopped into an ever-widening array of classic paintings, photos, and random situations? The common denominator in every explanation I have seen is the phenomenon of waiting. From stereotypes about the Russian people’s legendary patience to the Soviet experience of standing in endless lines, waiting appears to be a point of true commonality. Zhdun is claimed by Russia, Ukraine and Belarus, despite the obvious political issues that can divide them. Zhdun seems to require no particular political affiliation (the interview I quoted above was from Sputnik, a notorious Russian propaganda outlet).

But it is also possible to see Zhdun as very much a creature of the present moment. Dmitry Travin writes:

The conservative Zhdun thinks that the country’s president had long been duped by government liberals, but now he has finally shaken them off and will accept an economic development program in the national interest. The liberal Zhdun thinks that the president had long been cooped by the siloviki, and didn’t understand how bad things had gotten in our economy.

[…]

The young Zhdun is waiting for a change of elites and hopes to get a place in Gazprom […] The old Zhdun is waiting for order to be restored, for the enemies to be destroyed, for the USSR to be revived […]

All of this may be true, but, in the context of the various post-Soviet identities examined so far, Zhdun is both an identity and a meta-identity. He is a rare national image with which everyone can identify, but that is because he also represents the very problem that stands in the way of a stable post-Soviet identity. He embodies the patient expectation of something else. Zhdun is placeholder for an identity, well aware that his function as a placeholder is in itself representative of a state of suspension that has been, for better or for worse, rather stable.

In this, he only makes sense as the herald of whatever comes next. His patience suggests a refreshing optimism about whatever that may be. After all, Zhdun would make a terrible forerunner of the apocalypse. No rough beast, slouching toward Bethlehem, he is placid, cozy couch potato, content to sit wherever he has been left, staring straight ahead until something new starts to unfold before his wide-open eyes.

Next: Chapter 2:

Whatever Happened to the New Russian?

Late to the Party