Emily Wang is an Assistant Professor of Russian at the University of Notre Dame and the author of Pushkin, the Decembrists, and Civic Sentimentalism.

This post is based on an article that appeared in 2023 in Canadian Slavonic Papers / Revue Canadienne des Slavistes. The full text is available here.

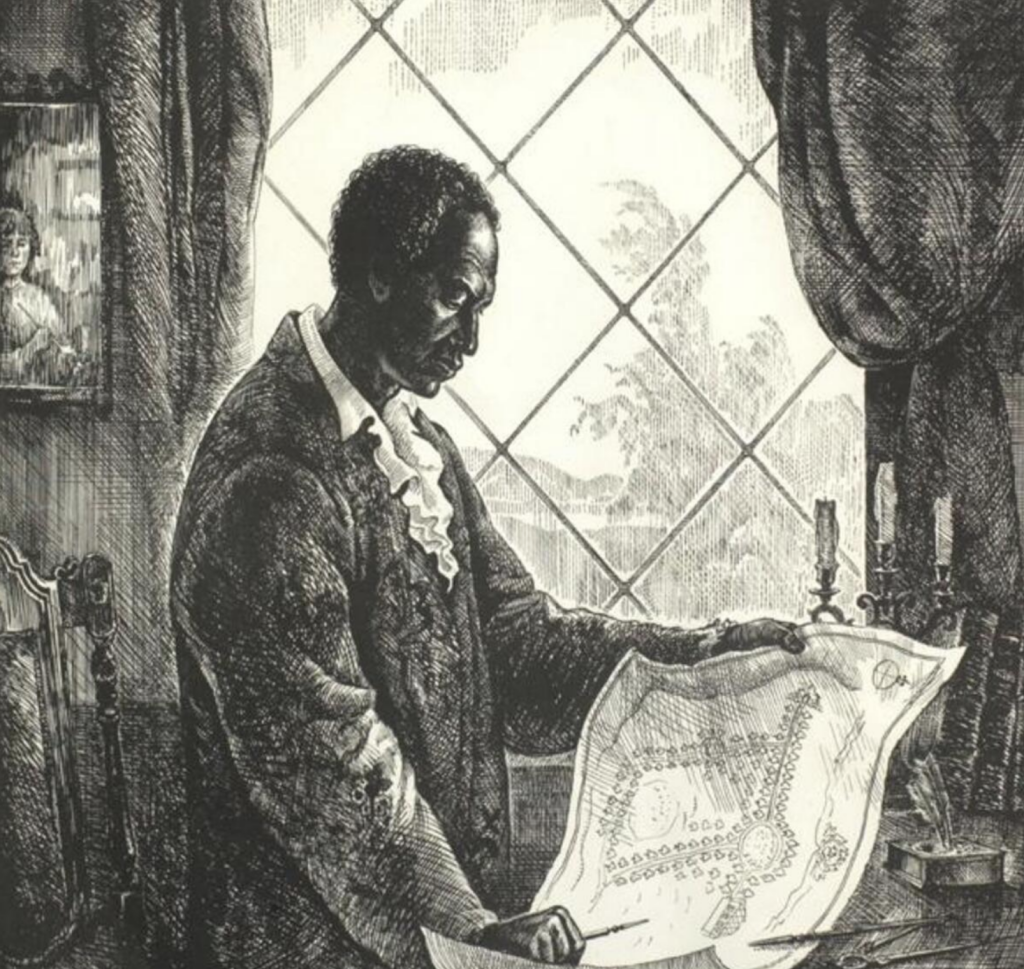

We know Alexander Pushkin as “Russia’s great national poet,” but we sometimes forget that was more than that. His great-grandfather was Abram Gannibal, a military engineer who rose to the rank of general in the Russian Empire after being kidnapped from present-day Cameroon as a child, and gave the Pushkin family Black ancestry. Moreover, this poet was more than just a poet: as tastes and audiences shifted, Pushkin began to write in prose in 1830.

Along with his talent, Pushkin’s unique ancestry was central to his youthful reputation. At school, he was nicknamed “African” or “Tiger-Monkey” (as well as “The Frenchman”). Memoirist Filipp Vigel’ compared the Pushkin who composed the famous liberal ode “Liberty” around 1817 to “Negroes and the human-like inhabitants of Africa.” Contemporaries like the Decembrist Vladimir Raevsky associated Russian serfdom and American slavery, and this association may have been part of the reason why Vigel’ associated Pushkin’s youthful liberalism with his African ancestry.

Other memoirists consistently remark on Pushkin’s African roots, though some note that these roots are less visible than they expected, making the poet what I call “racially ambiguous.” Mikhail Iuzefovich remarks that Pushkin “wasn’t dark at all,” and the poet’s great friend Prince Pyotr Viazemsky calls him “a bit like a dark-skinned Arab […] a white Negro.” Others, like salon hostess Daria Fikel’mon, declare that Pushkin’s Blackness was evident and made him ugly and wild. Many who knew Pushkin associate his hot-headedness—as an aspect of his personality that was sometimes visible and sometimes not—with his “seething” African blood.

Therefore, Pushkin may have been drawing on his own experiences when he created Liza Muromskaya, the heroine of “The Lady Peasant” (literally, “The Noblewoman-Peasant,” “Baryshnia-Krest’ianka”), the last story in his first cycle of prose stories, The Tales of the Late Ivan Petrovich Belkin, written in 1830 and published in 1831. This story, firmly embedded in the Russian literary canon, has been adapted numerous times, to films, operettas, and ballets. Its name was even used for a store selling Orthodox women’s apparel.

This iconic heroine is a crafty Russian noblewoman with relatively dark skin. (Pushkin calls her smuglaia, or “swarthy,” four times over the course of the story’s twenty pages.) She disguises herself as a peasant girl to meet Aleksei Berestov, the handsome son of her father’s enemy. Later, she uses English powder to whiten her skin and disguise herself as a French-speaking Westernized woman to avoid being recognized when he visits her house. Like Pushkin himself, Liza is associated with both dark skin and her fluent command of a Western idiom. (Notably, the best known film adaptation, by Aleksei Sakharov in 1995, deemphasizes Liza’s color.)

The story ends happily when young Berestov encounters her true self and they marry. The story depicts a woman who plays with the class divisions that many of Pushkin’s liberal friends associated with race, drawing parallels between American slavery and Russian serfdom. It also explicitly thematizes skin color: Liza uses her dark skin to pretend to be a sun-tanned peasant and then disguises it with makeup to seem Western.

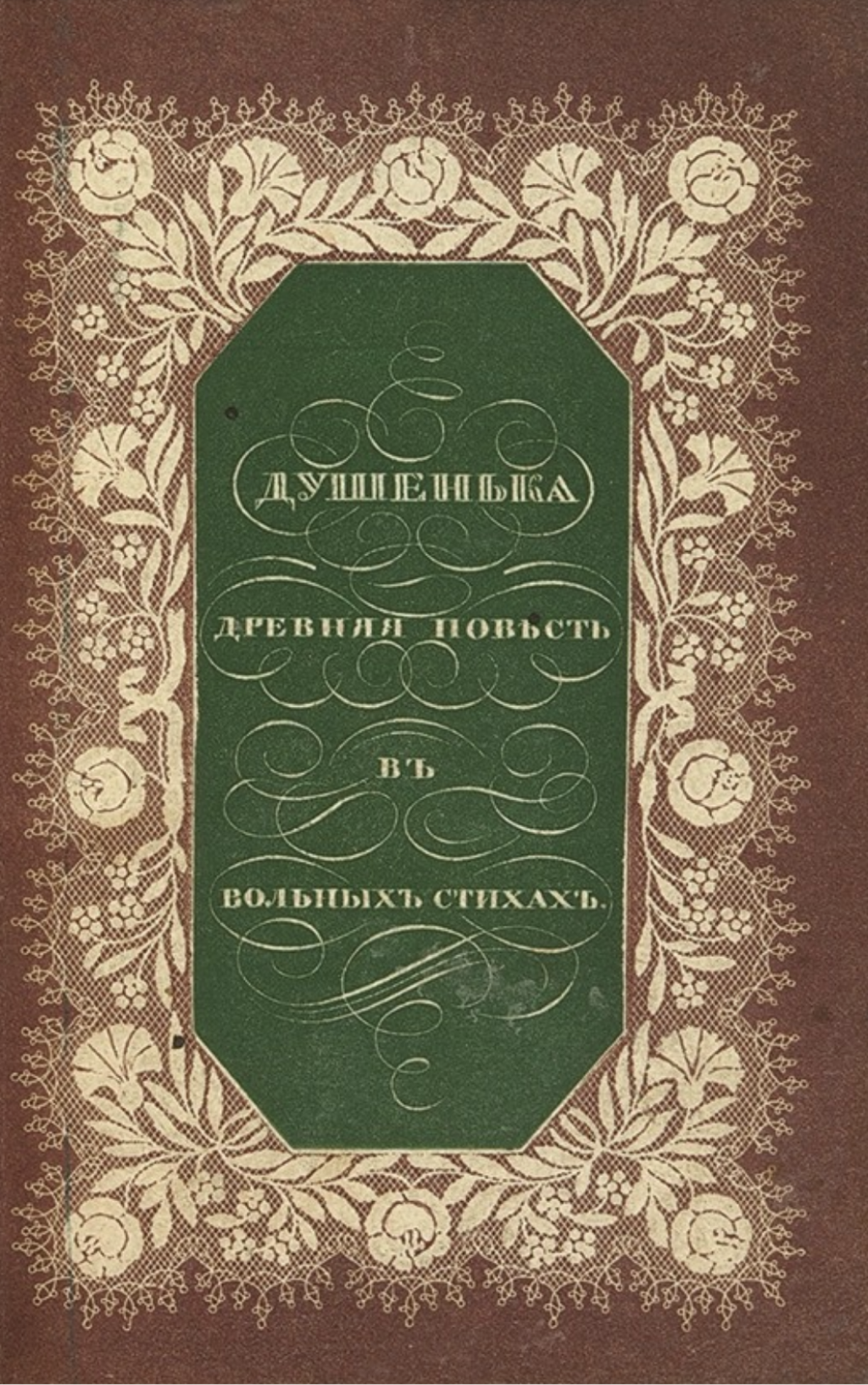

Indeed, several of the source texts that inspired Pushkin thematized racial transformations, although they went in the opposite direction. Ippolit Bogdanovich’s 1778 Dushenka, a retelling of the story of Psyche and Cupid from which Pushkin took his story’s epigraph, depicts an angry Aphrodite cursing the heroine with dark features. Pytor Makarov’s 1805 story “The Imaginary African Woman” tells the story of a nobleman who abandons his wife for a beautiful “Creole” woman, only to be effectively seduced again by his wife in Blackface. Notably, in his depiction of Liza, Pushkin omits the negative associations with Blackness that plague these source texts.

When thinking about race and “The Lady Peasant,” we should not forget that Pushkin’s first serious efforts at prose was a novel about Abram Gannibal (slightly fictionalized as Ibrahim), a novel that we now know as Peter the Great’s African. Pushkin never gave the work a title, though he did produce seven chapters in 1827. Like “The Lady Peasant,” the extant chapters of this work thematize race and Russia’s relationship to Western culture. Unlike the later story, the unfinished novel was not slated to end happily. Scholars like Catherine Theimer Nepomnyashchy have connected Pushkin’s reluctance to complete the text to his fear that his own impending marriage with Natalia Goncharova might end in infidelity, like Ibrahim’s. It is likely that Pushkin was thinking about his first efforts at prose literature when he wrote The Tales of Belkin. Indeed, the introduction to the text refers to the pages of Belkin’s unfinished novel being used to seal the house’s windows.

Pushkin was consistently preoccupied by his own ancestry, both its racial origins and its illustrious links to powerful figures like Peter I. Yet just as his contemporaries struggled to define him (recall Viazemsky’s “white Negro”), the poet also struggled to define himself. As Pushkin wrote in an 1818 love poem to the serf actress (a person who straddled the cultural divide between the classes, like Liza):

| Не владетель я Сераля, | I’m not the proprietor of a seraglio, |

| Не арап, не турок я. | Not an African, not a Turk. |

| За учтивого китайца, | You couldn’t take me for a polite Chinese man |

| Грубого американца, | Or a rude American, |

| Почитать меня нельзя, | |

| Не представь и немчурою, | And don’t imagine a Kraut |

| С колпаком на волосах, | With a cap over his hair, |

| С кружкой, пивом налитою, | A mug full of beer |

| И с цигаркою в зубах. | And a little cigar in his teeth. |

In the poem—his first extant poem in Russian—the teenaged Pushkin finally decides that he is a monk (in reference to the Lyceum’s strict curfew rules). Yet readers today might conclude, on the basis of texts like this one, that Alexander Pushkin was racially ambiguous.

We see in “To Natalia” how he takes advantage of his identity for the purposes of humor and art. Like his heroine Liza Muromskaia, an unusually dark-skinned, upper-class girl who pretends to be both a tanned peasant and a light-skinned lady, Pushkin used his ambiguous features to his advantage. Here, in these literary depictions of role-playing, we can glimpse the roots of his own multifaceted artistic personality.