David Brandenberger teaches courses on eastern Europe and Eurasia, nationalism, socialism, propaganda and historiography at the University of Richmond. He’s published on Stalin-era propaganda, ideology and nationality policy in journals like Russian Review, Slavic Review, and Kritika and written or edited nearly a dozen books including National Bolshevism (Harvard, 2002), Propaganda State in Crisis (Yale, 2011) and Stalin’s Master Narrative (Yale 2019). Brandenberger is presently finishing a monograph on the purge of Stalin’s would-be successors, the 1949 Leningrad Affair.

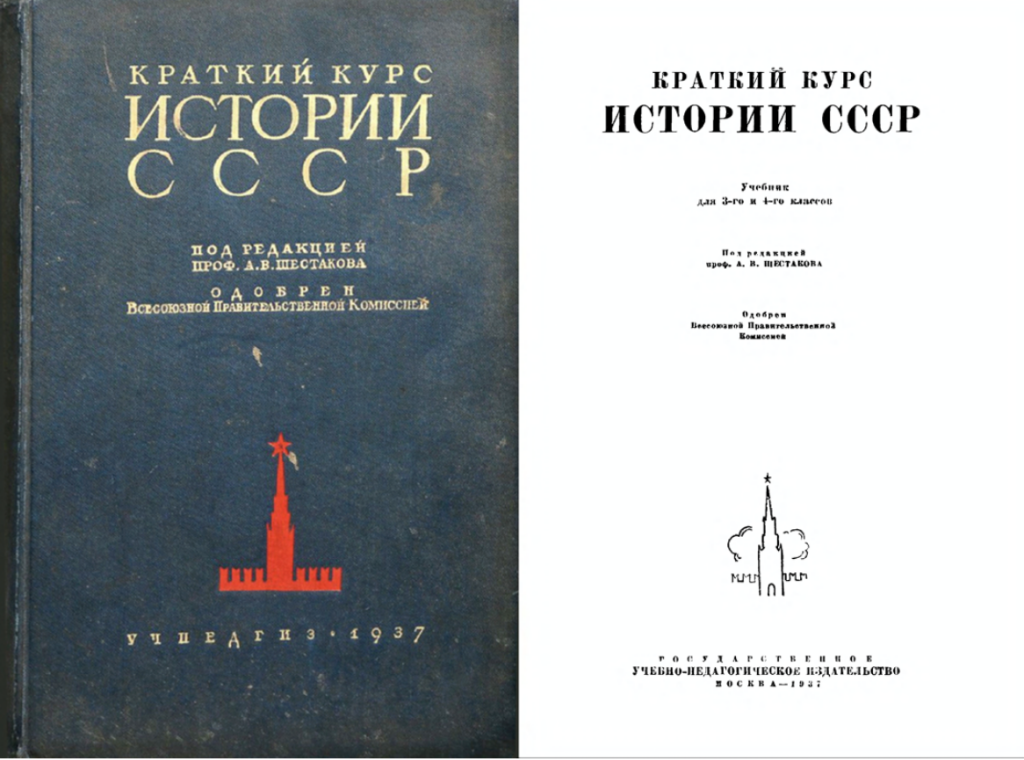

In the fall of 1937, Soviet publishers released Andrei Shestakov’s Short History of the USSR—a textbook that Joseph Stalin had taken a personal role in editing. Designed for use in the public schools, the Short History boasted an official endorsement—something that quickly led it to be adopted for use elsewhere in adult political education courses and Red Army study circles. This endorsement also transformed the textbook into a reference work for other historians writing about the past, as well as authors, playwrights, cinematographers, and even museum curators. And while it is true that the Short History was withdrawn from the public schools in 1956 in connection with destalinization, elements of the narrative continued to influence the USSR’s official views on the past through 1991.

Amid ongoing discussions about decolonizing the field of eastern European and Eurasian studies, it would seem timely to assess the degree to which Stalin’s Short History endorsed an imperial vision of the region’s past. As Terry Martin demonstrated two decades ago, most scholars agree that empires should be thought of as political systems within which one group dominates another and where this inequality between rulers and the ruled is reinforced over time. So to what extent is a defense of domination, inequality and elite rule present in Shestakov’s Short History?

As is apparent from a new critical edition of this textbook that I published in 2024, the narrative defies easy categorization. Although the Short History begins in antiquity with a brief discussion of specific regional peoples and their autochthonic territorial claims (Georgians and Armenians in the Caucasus, Uzbeks and Turkmen in Central Asia, etc.), it really only gets underway in Chapter Two with a state-building storyline focusing on the Varangians’ founding of medieval Kyiv Rus’.

Although the text stresses the ethnographic diversity of the region, neither the growth of Kyiv nor Muscovy is described as an imperial process. This omission is due at least in part to the fact that Vladimir Lenin’s understanding of imperialism was tied to the maturation of a capitalist economy. Instead, the growth of Muscovy is initially discussed in terms of the rise of a “Russian national state”—a concept that stemmed from Stalin’s understanding of premodern eastern Europe, where large states formed before nations did. Only with the beginning of Muscovite expansion into Siberia under Ivan IV did Shestakov direct readers’ attention to the conquest of non-Russian peoples and the rise of a multiethnic polity.

Despite the colonial dimensions of this later Siberian expansion, the Short History did not actually invoke the term “empire” until Peter the Great was formally crowned emperor in 1721. That said, the narrative from the mid-seventeenth century forward includes circumstances that many modern observers would recognize as imperial: the acquisition of non-Russian territory through war and/or co-optation of local elites, the maintenance of peripheral regions as separate, subordinate entities, etc.

Although Shestakov’s various predecessors frequently described this period of imperial growth as wholly exploitative in both economic and colonial terms (resulting in the formation of what Mikhail Pokrovskii called a “prison of peoples”), Stalin and his ideological advisor Andrei Zhdanov insisted that this schema be nuanced in order to explain the logic of this empire building. Their approach, dubbed the “lesser evil” thesis, called for events such as the mid-seventeenth century co-optation of Ukraine to be evaluated as historically progressive, insofar as Soviet leaders believed that the Cossack Hetmanate was incapable of defending itself against regional superpowers such as Muscovy, the Polish Lithuanian Commonwealth and the Ottoman Empire.

In such a context, they averred, the “lesser evil” for the Cossack elites was to subordinate themselves to their Muscovite co-religionists. Similar scenarios were subsequently devised to explain the conquest of other territories in the Caucasus and Central Asia. The same logic likely explains Stalin’s decision to delete discussion of the cruelty of some of these campaigns and the degree to which many of these non-Russian peoples resisted the new imperial order.

In places where the “lesser evil” thesis proved unable to nuance this expansionism—in the west, for instance, in Polish, Baltic and Finnish lands—territorial acquisitions were cast as elements of pre-revolutionary Russian state-building rather than empire building. This framing continued into the nineteenth century, when even explicit imperialism was understood first and foremost as an economic process rather than as the imposition of a regime of imperial dominance. The imperial nature of the tsarist system was also balanced with constant reminders in the text that it was the Russian peasantry and nascent working class in the metropole who were the greatest victims of this exploitative system, rather than the non-Russians on the periphery.

After the revolutions of 1917, the imperial subplot in Shestakov’s narrative effectively disappears from the text, except when explaining foreign capitalists’ eagerness to overthrow the new Soviet republic. This is because the textbook characterizes the October 1917 revolution as liberationist in both class and ethnic terms. Thereafter, the Short History stresses the equality of Russians and non-Russians alike and describes differences in cultural and economic development on the periphery as something that the altruistic metropole would correct in short order.

In sum, while a red thread of imperial relationships is present throughout Shestakov’s Short History, the theme is regularly subordinated to more statist ones. The narrative, for example, is organized around a unitary, russocentric storyline that stretches in linear fashion from medieval Kyiv through Muscovy to the Soviet Union. Insofar as non-Russian people appear in this emplotment only in passing, it would appear at first glance to be a story of empire and colonial conquest when they come into contact with the expanding Russian juggernaut. That said, it is also simultaneously a story of state-building and top-down governance, since much more attention is cast toward the growth of administrative power at the center than exploitation on the periphery.

Indeed, even when the text focuses on explicitly imperialistic moments, such as the incorporation of left-bank Ukraine or Georgia into the empire, it describes these events with enough nuance to prevent the polity from being labeled a “prison of peoples.” Moreover, if the theme of empire is visible at the climax of the narrative in the leadup to 1917, it vanishes entirely thereafter. In the final chapters of the textbook, all attention toward empire is replaced by a new anti-imperial focus on equity and broad-based economic development that combine to advance Soviet claims of prosperity through the building of socialism in one country and the abolition of all forms of inequality.

Amid all of this caution and nuance, a case could still be made for classifying the Short History’s stress on Russian arts, letters, and scientific accomplishments before 1917 as a sort of cultural imperialism. That is because this russocentric approach to cultural development implies that non-Russian forms of self-expression were inferior in terms of creativity and sophistication. But it would be wrong to extend this judgement to the political aspects of the narrative, insofar as the Short History called upon the Russian people to share the benefits of their economic and cultural development altruistically, without any promise of special political rights or entitlements in return.

It is also possible that the selectivity of this russocentric narrative’s thousand-year arc should be seen as a form of historical imperialism. After all, as Alexey Golubev pointed out to me recently, it is the epistemic erasure of competing non-Russian narratives that allows the textbook to present the growth of the Russian empire as a “lesser evil,” if not a completely natural and inevitable process. And while Stalin, Zhdanov, and Shestakov may not have been aware of the implications of this aspect of their storytelling, others clearly were. Volodymyr Zatonskyi, for instance, the Commissar of Education of the Ukrainian Republic, denounced an early draft of this textbook precisely because it failed to offer a broader history of all the peoples of the USSR.

So while it is important to concede that this officially anti-imperialist textbook demonstrates some of the trappings of an imperial narrative, it is also important to see the Short History as subordinating both its critique and endorsement of empire to a much more dominant theme: the celebration of state-building on either side of the revolutionary divide.