On October 5, 1928 the Jewish Telegrahpic Agency published this short dispatch from Moscow:

“The Soviet Government of the Ukraine was criticised in the official organ of the Moscow government, “Pravda”, for permitting the publication by the government press of a Russian language dictionary where the insulting term “Zhid” is included as a noun for Jew.”

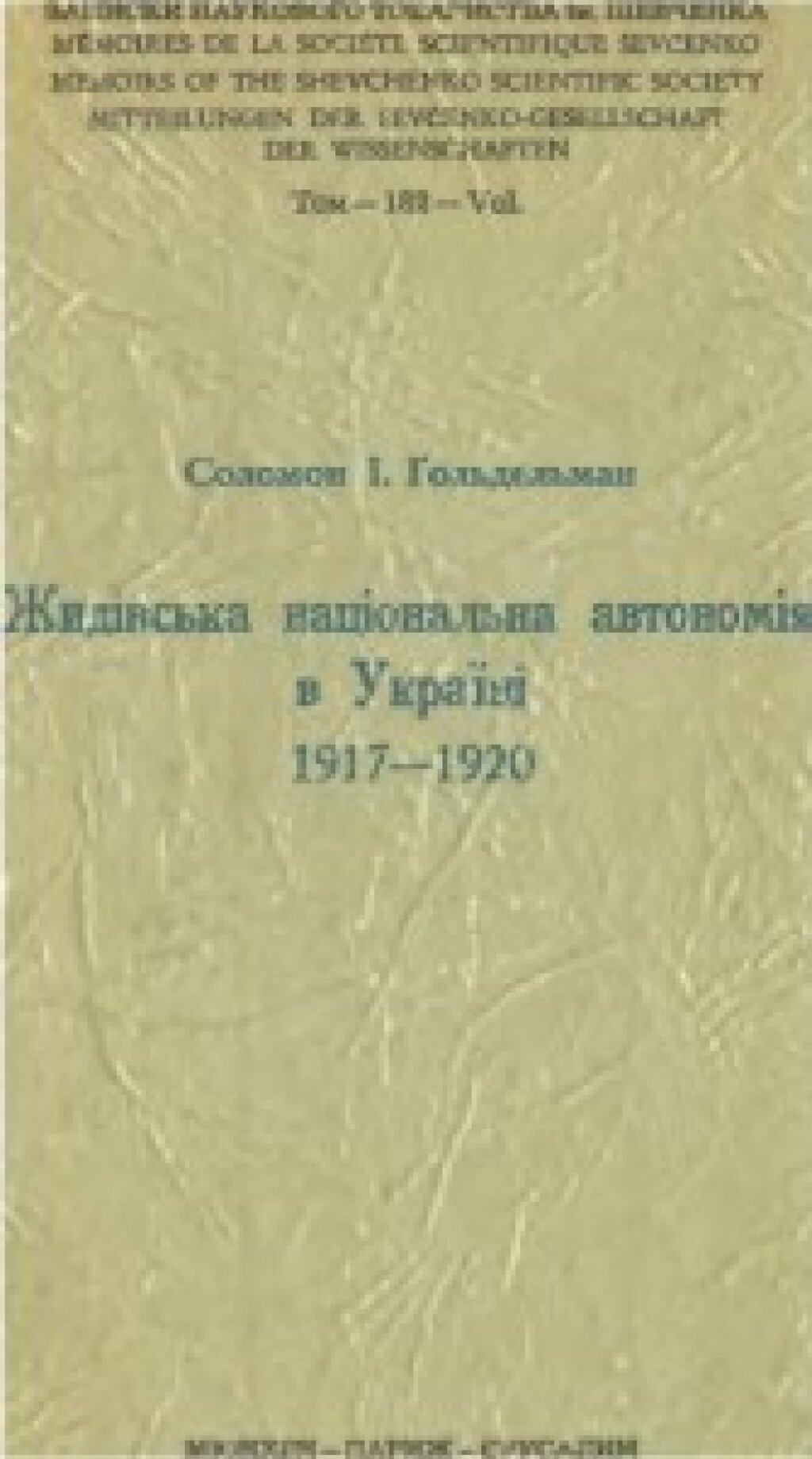

Without any knowledge of the Ukrainian language, this would seem like a run of the mill Soviet condemnation of anti-Semitism. Stalin himself once called anti-Semitism “a phenomenon deeply hostile toward the Soviet order.” However, prior to the Soviet standardization of the Ukrainian language (which many Ukrainians refer to as “Russification”- more on that later), the word zhid (жид) was the only Ukrainian word for a Jew. Unlike Russian, which includes the neutral term “yevrei” and the pejorative term “zhid” - Ukrainian only had the term zhid- and it was not considered pejorative.

In his memoirs Khrushchev describes the strangeness of hearing the term “zhid” used in polite conversation during a visit to a Communist Party meeting in newly acquired Western Ukraine:

“Jews spoke at the meeting… and it was strange for us to hear what they said: ‘We zhidy proclaim in the name of the Zhidy and so on… They called themselves that in everyday speech without intending any offensive meaning. But we soviet citizens perceived it as an insult to the Jewish people. Later… I asked them… They answered: “But for us it’s considered insulting when we are called ‘yevrei’”

This seems like a textbook example of what Ukrainian speakers lament. When something in the Ukrainian language sounded strange to native Russian speakers it was changed-regardless of historical context. Thus, for many Ukrainians it is impossible to view the Soviet standardization of their language as anything but Russification. In this narrative, Soviet standardization and Russification become interchangeable- a phenomena that would be harder to parse out when looking at Sovietized non-Slavic languages like Mongolian or Tajik.

The Russification or Soviet standardization of the Ukrainian language came up in the first week of my introduction to the Ukrainian language this summer. Every language includes regional variations and every language includes terms whose definitions bring up painful moments in the national memory. Yet, the conversations my Ukrainian 101 class has had about Ukrainian history in response to basic grammar lessons do not resemble anything I’ve encountered in studying Russian, French, or Hebrew. The majority of these conversations center on so-called “diaspora” Ukrainian versus the Ukrainian spoken in today’s Ukraine. Simply put, “diaspora” Ukrainian reflects the Ukrainian spoken in former Galicia and other parts of Western Ukraine where most of the Ukrainian-speakers in Canada and the United States hail from. This Ukrainian is characterized by English language influences (from living in North America) as well as influences from the German of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and Polish- and fewer influences from Russian. Ukraine’s Ukrainian reflects Soviet standardization as well as fewer influences from Polish (given the vast amount of ethnic cleansing on the Polish-Ukrainian border). The differences can be so stark that a friend of mine who grew up in the Ukrainian diaspora in Ohio and spent a year in Kyiv created a “Diaspora Ukrainian” to “Modern Ukrainian” dictionary for himself. Thus, in class my Ukrainian instructor often points out to us the terms in our Ukrainian textbook that would sound out of place asking for directions in Kyiv, but perfectly normal in Chicago’s Ukrainian Village. Our textbook leans toward diaspora Ukrainian perhaps because it was funded in large part by members of the Ukrainian diaspora in the U.S and Canada. Yet, even as this textbook rejects so-called “Russified” grammar structures and vocabulary, it does not offer the word “zhid” as a proper term. I think you would be hard pressed to find someone who uses the term “zhid” as their go-to example of Ukrainian linguistic oppression. Ukrainians who lament the Russification of their language still use the term “yevrei.”

In thinking through this particular example I am reminded of how much Russian propaganda against Ukrainians in this current conflict hinges on Ukrainian treatment of Jews. The Donetsk People’s Republic recently put up a portrait of Stalin outside their Opera House- and despite Stalin’s earlier quotation about the dangers of anti-Semitism- he’s the man responsible for show trials across the Soviet Union and Eastern Europe that executed countless prominent Jews. While Putin’s Russia seems to forgive Stalin for his crimes (against Jews and millions of others), Russian media outlets continue to focus on the atrocities committed against Jews by the Ukrainian heroes whose monuments increasingly replace old Lenin statues.

This debate about whether Ukrainian’s WWII era nationalist partisans were worse to the Jews than Stalin’s Soviet Union is a strange one and I’m not sure what it means to win. What I do know is that Russia has set the terms- and Ukraine’s response of jingoistic memory laws is not helping their case.

Neither side has adequately dealt with its history concerning Jews, Poles, and countless other episodes of ethnic cleansing - but in the current conflict it’s only Ukraine that’s on trial. As an American who grew up taking my dogs to Robert E. Lee Park, it would be silly of me to say this is a problem unique to the region. Yet, as long as the Russian propaganda that portrays Ukrainians as “fascists” (a characterization dating back to the Soviet era) dictates the terms of this reckoning with history we are stuck with censored texts instead of meaningful debate. Just as the erasure of the term “zhid” is an example of the Russification of the Ukranian language, the framework for Ukraine to deal with its history has also been Russified. The Soviets literally took the words away from Ukrainians in how they understood their relationship to their Jewish countrymen and the same may be happening again. The solution is not for memory laws to create a new iron-clad framework but for an entirely new conversation- but not on the terms set by Putin. If Khruschev could learn to see Ukraine’s relationship with the “zhidy” as separate from Russia’s, than we should too.