Alison Rowley is Professor in the Department of History at Concordia University in Montreal and President of the Canadian Association of Slavists. She is the author of Putin Kitsch in America (McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019) and Open Letters: Russian Popular Culture and the Picture Postcard, 1880-1922 (University of Toronto Press, 2013).

I squealed like a young teenager attending their first concert when I saw this picture taped to the front of the box in my hands.

I had been coveting this piece of Putin memorabilia for months — probably driving family and students alike crazy with my constant comments about it — but could never justify spending close to $100 to buy it. While I delighted in this gift on Christmas morning, my husband’s response was more muted. “You're not putting that on the nightstand, are you?” he asked wearily, having grown tired of discussing Putin objects with me and probably finding my ever-expanding collection more than a bit worrisome.

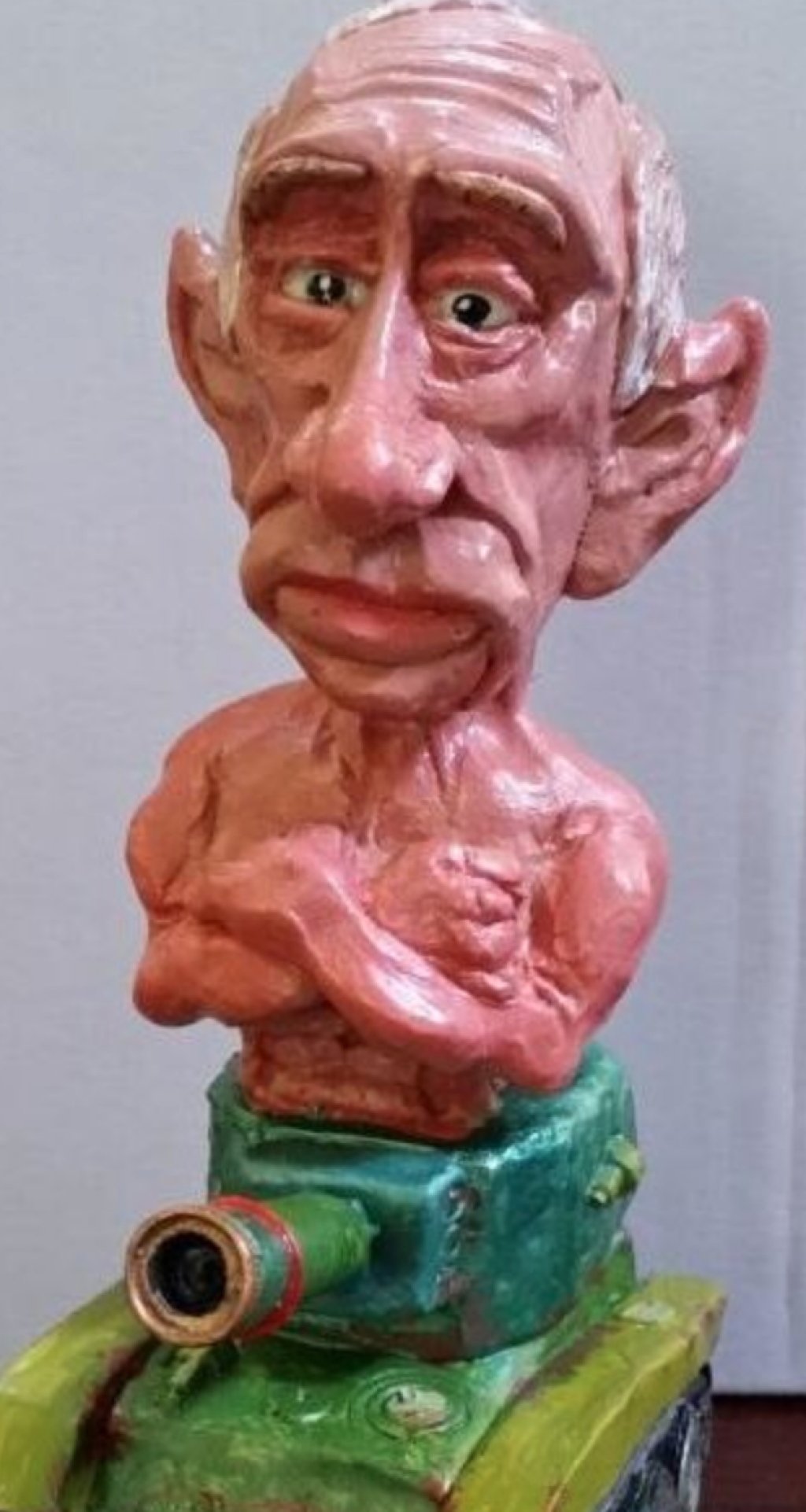

I first noticed the 7” hand-cast polymer Putin statue on Etsy.com in November 2017. For those who may not know, the website, which launched in 2005, sells an array of handcrafted and vintage merchandise. It went public with a $100 million IPO in 2015 and, on the day that I write this post, has a very respectable Alexa internet traffic ranking of 108. That means Etsy gets quite a lot of people — think millions — looking at its website every day and it is one of the places where I regularly search for new items of Putin kitsch for my research. As the below photograph demonstrates, the garden gnome was a simply spectacular piece.

The seller, who calls himself Sniglart, markets his politicalized gnomes through an Etsy storefront called Kretacean. The listing for the Putin gnome was delightfully playful in nature but also showed a solid engagement with contemporary politics. It read, “He’s coming to invade your neighbors’ gardens and he might even decide to turn up to the G8 summit in his armored car…yes, by popular request, and with no fear of poisoned umbrellas, I present….Vladimir Putin, the garden gnome.” Of course, in tongue-in-cheek fashion, Sniglart went on to warn potential buyers that they “risk him herding…other gnomes into a gulag!!!” (exclamation points in the original)

The Putin gnome calls out to me for several reasons. First, like many pieces of Putin memorabilia, it plays with the public image that has been constructed for the Russian President. Here, the gnome arguably mocks Putin’s credentials as a masculine military leader by (of course) presenting him without a shirt, but also by giving him with a rather puny, unimpressive physique. The overtly sexualized nature of much Putin propaganda — a phenomenon discussed at length in works by Valerie Sperling, Helena Goscilo, Julie Cassiday and Emily Johnson — is suggested by the position of the tank turret, which looks like an erect penis pointing at the viewer. But that is not all. It is worth remembering where this item could be found — online, made in Britain, and for sale on a US website. Hence, the gnome speaks to the international nature of Putin’s public persona and its material manifestations. In other words, it is not just Russians who live with Putin kitsch; we all do.

Images of Putin now permeate political and popular culture across the globe. Rather than decry his influence, I see how many people have used references to the Russian leader, particularly in the United States, as a lodestone. Such a stereotypical figure makes a convenient reference in critiques of one’s own political leaders. The first vein of Putin kitsch to act in this manner appeared in the 2008 election cycle, after Putin had undergone an image makeover (those first shirtless photographs appeared in August 2007) and as Sarah Palin made her unfortunate comments about Alaska’s proximity to Russia giving her foreign policy expertise.

Barack Obama’s victory shifted the discourse, with Putin memorabilia of all kinds now being used by people with more conservative viewpoints as they commented on what they viewed as the new US President’s lack of experience and inadequate masculinity for the job. Unsurprisingly, given that tropes of masculinity are still so prevalent in contemporary US politics, Putin was the standard by which many Americans measured the candidates as they ventured to the polls in 2016. Only now, Putin’s image was being weaponized by people with left-leaning sympathies who were keen to see Donald Trump defeated. The attacks took politicized kitsch well beyond such familiar items as bumper stickers, campaign buttons and T-shirts. Soon the internet was awash with everything from erotic fiction, memes, and parodies that could be printed onto every conceivable object — and even handicrafts like our garden gnome.

In the three years that have followed Trump’s election, none of what I have been describing has disappeared. Instead, the creativity, especially of young people who are tired of traditional ways of doing politics and who live in a more digital way than previous generations, has exploded. Recent news stories about TikTok users disrupting the Trump re-election campaign through the manipulation of ticket reservations for political rallies or through shopping cart abandonment (which affects the volume of merchandise that can be sold and hence the funds coming into a campaign’s coffers) should make any pundit pause before expressing an opinion about political engagement.

Nor has Putin been forgotten. The face mask I ordered a couple of weeks ago in response to the Covid-19 pandemic is covered with mini-Putin heads. More seriously, the Russian referendum that finished on June 30 enables him to run for another two terms, meaning Putin will likely occupy the presidency until 2036. Given that American culture’s fascination with his image has yet to be exhausted, it makes one wonder what kinds of objects I might be writing about in years to come.