We at the Jordan Center stand with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

This is Part I of a two-part series. Part II will appear tomorrow, 5/19.

Steven E. Harris is Professor of Russian and European history at the University of Mary Washington and author of Communism on Tomorrow Street: Mass Housing and Everyday Life after Stalin (2013). His current book project, Flying Aeroflot: A History of the Soviet Union in the Jet Age, examines the Soviet airline and aviation culture in late socialism. This blog post draws from his two recent research articles: “The World’s Largest Airline: How Aeroflot Learned to Stop Worrying and Became a Corporation” (Laboratorium, 2021) and “Dawn of the Soviet Jet Age: Aeroflot Passengers and Aviation Culture under Khrushchev,” (Kritika, Summer 2020).

On March 6, 2022, 13 Russian diplomats and their families flew home from JFK airport on the last Russian plane to leave the United States for the foreseeable future. In response to the war of aggression that Russia launched against Ukraine on February 24, many countries barred Russian airlines from their airspace. Russia retaliated in kind, even eliminating overflight routes airlines use to connect Europe with Asia. While a devastating conventional war continues on the ground in Ukraine, a cold war in the skies has divided the world anew between Russia and the West.

This blog post reflects on the historical significance of this sudden rupture in global aviation, focusing on Russia and the US in particular. I also consider what the original Cold War and the Soviet Union’s approach to civil aviation can tell us about what happens next.

The air routes that until recently connected Russia to the world were first forged in the Soviet 1950s and steadily grew across the socialist world, the West, and the Global South. Despite US attempts to limit Aeroflot’s international presence, the Soviet airline ultimately created a global route network.

Recent sanctions, in other words, have undone a largely forgotten Soviet legacy. The international air link infrastructure that has quickly unraveled was created in no small part by the Soviet Union. While radically different, Russia’s post-Soviet airline industry built upon its Soviet foundations, including Aeroflot’s global route network.

Belying the image of an impenetrable Iron Curtain, air routes connected the USSR and its Eastern European satellite states to many Western countries, bringing much-needed hard currency into socialist coffers. Bucking Cold War warriors’ paranoia about Aeroflot’s intentions, even the United States eventually welcomed socialist airlines to its airports.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, détente and air travel across the Cold War divide were mutually reinforcing in ways that suddenly feel quite distant today. The Ilyushin-96 jetliner that brought home the 13 diplomats and their families retraced a route that Aeroflot and Pan Am began flying in July 1968, connecting the metropolis of global capitalism with the capital of global socialism.

As I discovered in researching Aeroflot and Pan Am’s business relationship in Russian archives, non-state actors played a critical role in forging this route and making it work. When the two superpowers committed in the late 1950s to build an air bridge between New York and Moscow, Aeroflot received unsolicited offers from various American companies and even pilots eager to help the Soviet airline learn the ropes of the US market and earn its business.

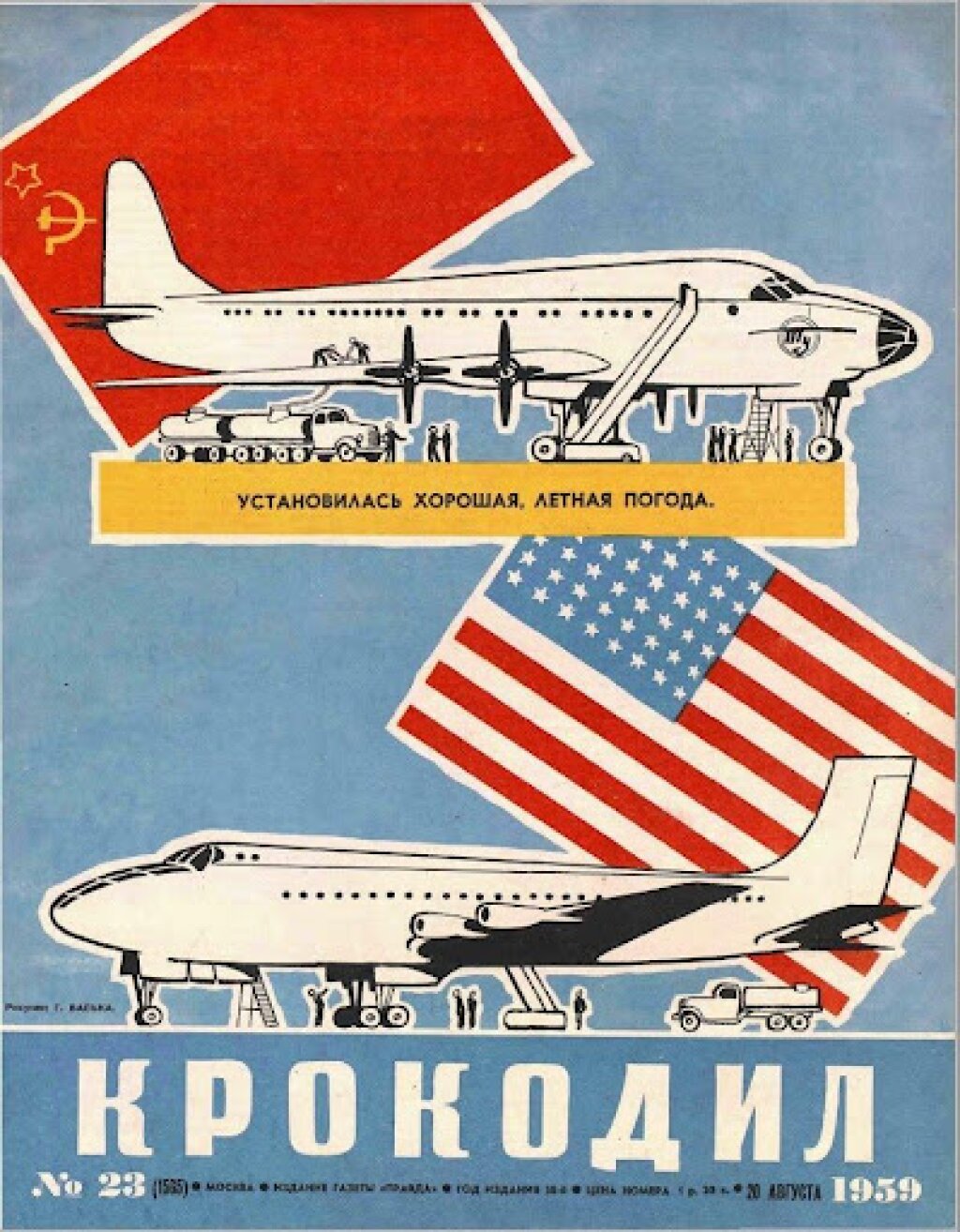

This front cover of the Soviet satirical magazine The Crocodile (Krokodil) nicely captures the era of good feeling in the late 1950s when the air bridge idea first took hold before a rash of Cold War incidents—such as the Gary Powers affair, the Berlin Wall’s construction, and the Cuban Missile Crisis—led to interminable delays in its finalization.

When flights between the two countries at last began, the Soviet carrier benefited from private businesses in New York, which Pan Am obviously lacked in Moscow. This included the help of two Jewish émigrés from the Russian empire who ran travel agencies and coached Aeroflot on navigating the American market. Neither fellow travelers nor anticommunists, Iulii Khorton of Union Tours and Gabriel Reiner of the Cosmos Travel Agency were outliers in an immigrant community with an understandably deep mistrust of the USSR.

Khorton’s and Reiner’s relationship with Aeroflot reveals the complex social, economic, and cultural relations that international air routes rely upon but also engender and sustain. And the two travel agents suggest the indispensable role that immigrants and others with ties to two hostile countries can play in smoothing over conflict.

After the USSR’s collapse, Russian commercial aviation dramatically changed with Aeroflot’s significant downsizing, the proliferation of new airlines, and the purchase or leasing of foreign aircraft. The integration of Russia’s airline industry in the global aviation economy after 1991 was successful. And overflight paths spanning Russian airspace, a rarity for foreign airlines in the Soviet era, finally became more widely available to them.

But Russia’s integration in global aviation and Aeroflot’s post-Soviet success as an international carrier have also led to the assumption that a country’s commercial aviation can only succeed in a globalized, Western-led system. Soon after Russia started its war against Ukraine, some hastily concluded that sanctions would not only bump Russia out of this system but potentially collapse its airline industry.

Yet, much like the ruble, Russia’s airlines and aviation manufacturing sector show signs of weathering the storm of sanctions and adjusting themselves to become less dependent on the West in the long run. While service, safety, and routes abroad may remain significantly stunted, Russia’s aviation industry is likely to rebound in service to the state, if not exactly the people. This means serving Putin’s regime not only economically but symbolically as a source of legitimacy and as a tool of geopolitical influence in its geopolitical space.

In this regard, Aeroflot’s Soviet past is instructive. In contrast to their Western counterparts, which constitute the default narrative in postwar aviation historiography, the Soviet Union and its sole airline successfully created an illiberal version of the Jet Age.

Aeroflot became “the world’s largest airline,” as one of its foreign ad campaigns boasted, and served the Soviet state’s political, economic, and symbolic interests first and those of its domestic passengers a distant second. The state heavily restricted its citizens’ foreign travel and even scuttled Pan Am’s earnest if somewhat naive attempts at advertising inside the USSR. And it censored news of Aeroflot’s crashes, most of its hijackings, and technological dependency on the West, lest any citizens think they didn’t live in the most advanced and caring state in the world.

Aeroflot’s Soviet incarnation is often dismissed as a failure by Western standards. I would argue that it’s more revealing, especially in the present moment, to appreciate how illiberal states successfully exploit technologies instead of assuming they inevitably lead to liberal outcomes in greater mobility, customer service, and international travel.

And so, as a consequence of sanctions, but also latent desires for greater autonomy from the West, Russia may similarly succeed as the USSR did at creating a distinctly autocratic and largely domestic version of air travel.