Featured

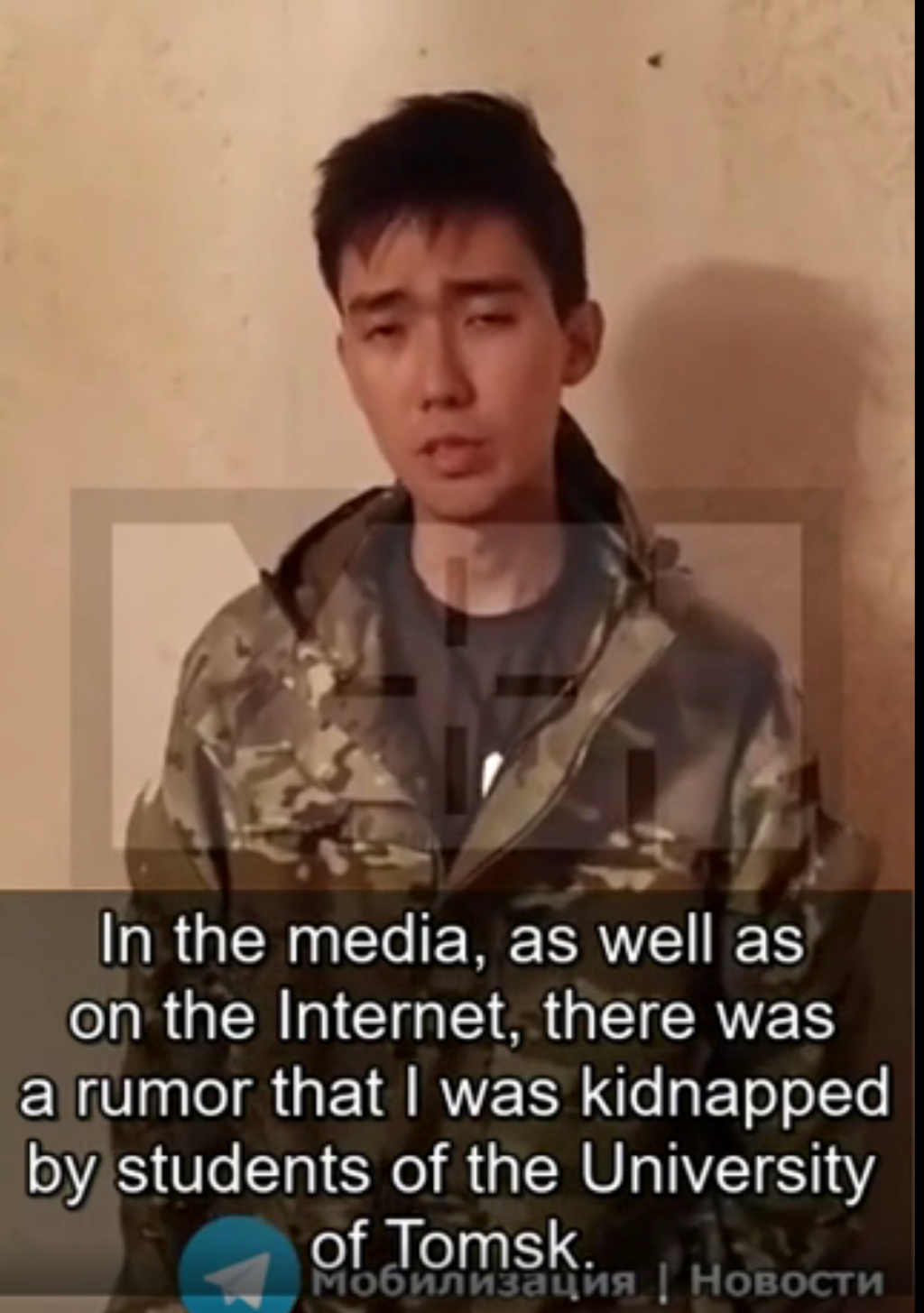

Wagnerites Turn International Students into Cannon Fodder

The Russian government and state-affiliated private mercenary companies are forcing international students to fight in Ukraine.

Russia’s Paramilitarization and Its Consequences

As much as a quarter of Russian forces in Ukraine are estimated to come from paramilitary organizations. Should elite infighting break out into the open, or Russia palpably lose the...

Exodus: Russian Repression and Social “Movement”

In past research, we identified several broad trends in Russian civil society prior to the war, which we labeled enduring, evaporating, and adapting forms of activism. These terms captured, respectively,...

Employee of the State, Enemy of the State: Teaching English in Moscow

I taught English as a Foreign Language in Moscow between 2019 and 2022, through mass student protests, increasing restrictions on freedom of speech, and, finally, a total break with Western...

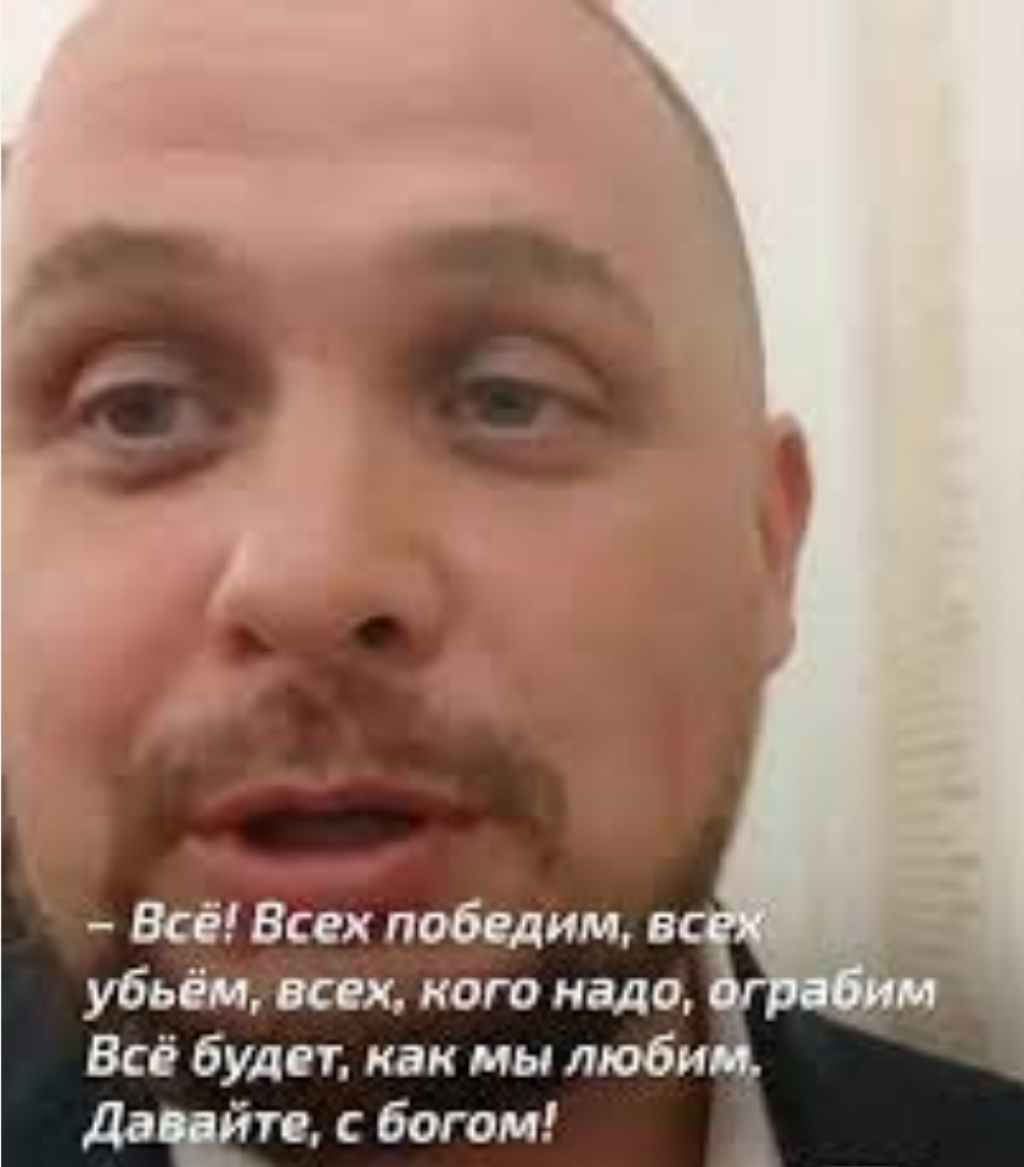

Unexpected Telegram: The Assassination of a Pro-Kremlin Blogger

Tatarsky's assassination signals that the internet and social networks are now far more than either a haven for anti-Putin oppositional voices or a dark space for Kremlin trolls.

Prosperity or War? "Peace" as a Political Tool in Today's Hungary

Since the outbreak of the war, the Hungarian government has consistently objected to providing military aid to Ukraine to help the country defend itself from its Eastern aggressor. Hungary has...

Vladimir Putin: War Criminal

In charging the Russian leader, the ICC becomes the latest international institution to go public with well-documented evidence of his culpability for the war against Ukraine.

When Russia’s Window on the World Slammed Shut: Reminiscences of an American Researcher, Part II

As I walked by the Ploshchad’ Vosstaniia metro stop, across from the Moscow Railway Station, a pop-up protest streamed past me, chanting: “Ukraine is not our enemy” and “No to...

When Russia’s Window on the World Slammed Shut: Reminiscences of an American Researcher, Part I

Cannons rang out and explosions shook the building, interrupting the singing onstage. What was going on? Was the war really here? No. It was just the salute to commemorate February...

On the First Anniversary of Russia's Invasion of Ukraine

Today marks one year since Russia began its illegal and immoral military invasion of Ukraine. We continue to be horrified at the wanton destruction and loss of life brought about...

One Year Ago: Helen Chervits' Eyewitness Report from Kyiv

It makes sense that politicians around the world are afraid of Putin. But Ukrainians are living in immediate fear for their lives right now. And we understand firsthand that Putin...

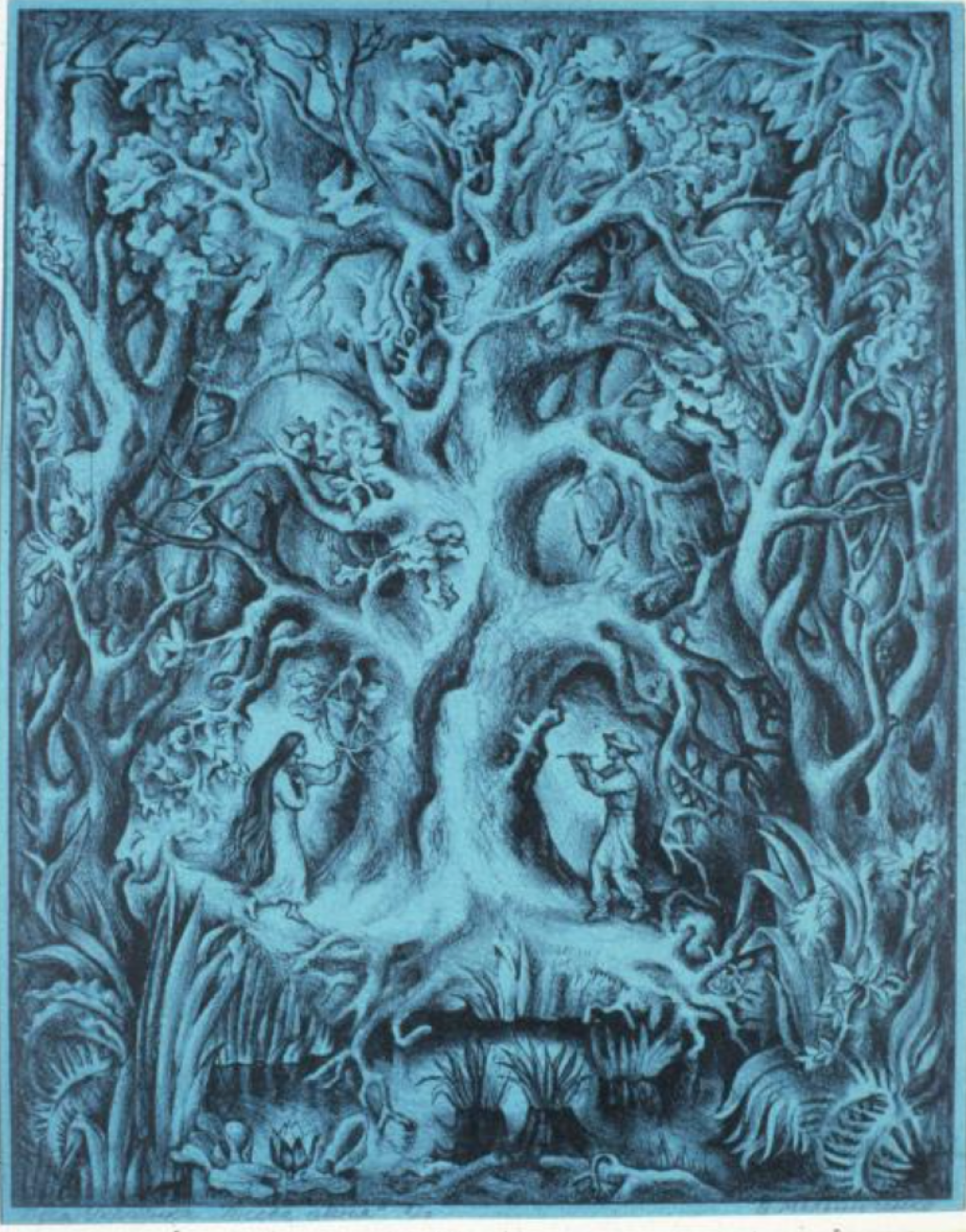

One Year Ago: Russia's War on the Nonhuman

In April 2022, I reflected on the environmental impact of the war in Ukraine by reimagining it through Lesia Ukraïnka’s fairy-drama "Forest Song." On the verge of the invasion’s one-year...

One Year Ago: Historian Victoria Smolkin Assesses Putin’s Claim that Modern-Day Ukraine is a "Gift" from the Bolsheviks

As a historian, what struck me most about the historical narrative of Vladimir Putin’s speech was not only what “historical facts”—to borrow his terminology—Putin used, but also what he left...

One Year Ago: Professor Natalia Levina Speaks on Ukraine at NYU

I grew up in Kharkiv. Countless memories are tied to the main city square, which has now been bombed. Almost a year ago, I learned that my own childhood home...

Always Alone? Russian Economic Isolation in Historical Perspective

Self-sufficiency now is the Putin's regime’s watchword. Nonetheless, as in Soviet times, today’s isolation is tempered in ways that belie the trope of a walled "Fortress Russia."

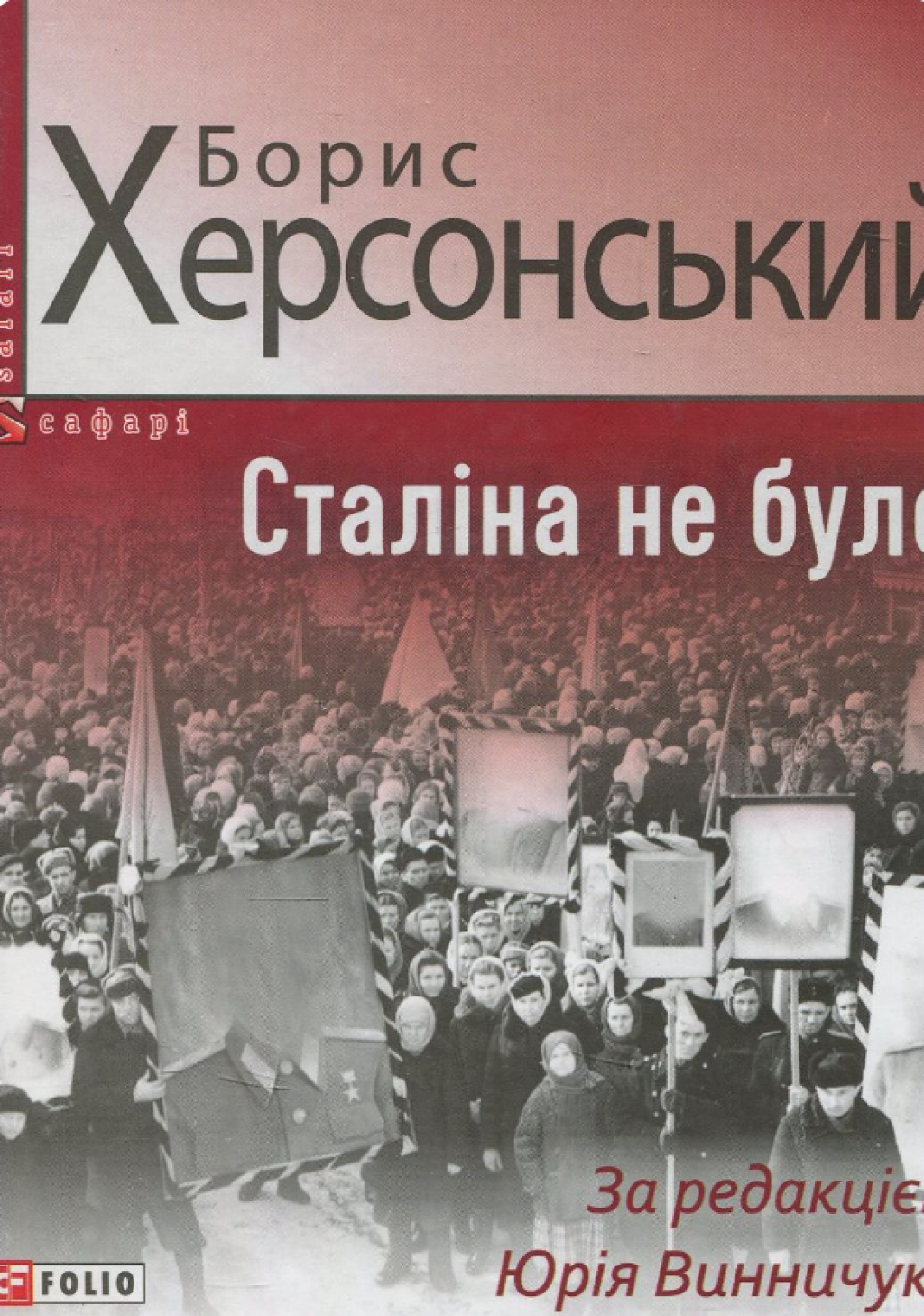

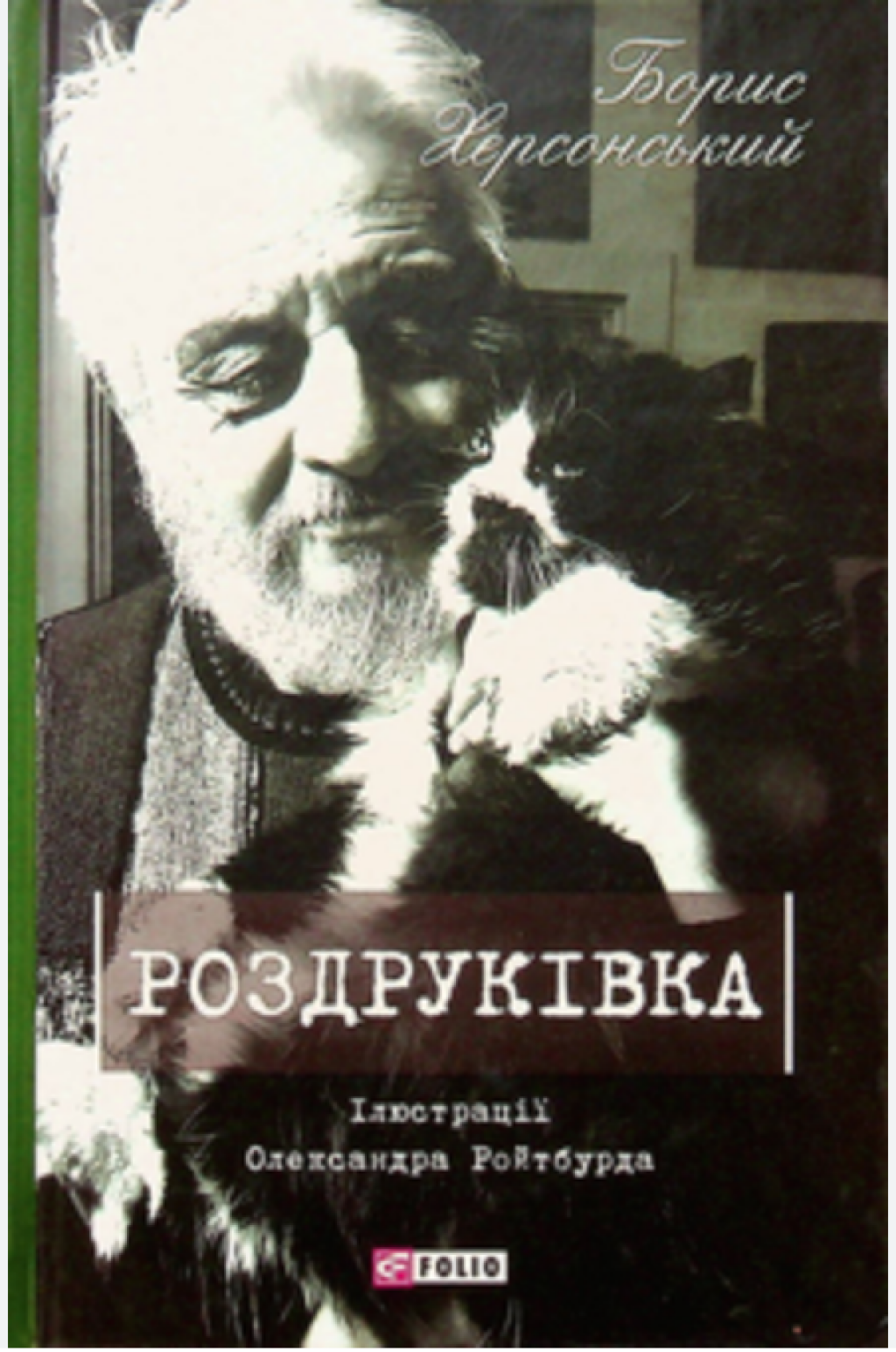

Anti-Hegemonic Code-Switching: The Case of Odesa Poet Boris Khersonskii, Part III

Taken together, Khersonskii’s posts imagine a future multilingual society that recognizes the civic obligation of understanding and speaking Ukrainian. His own bilingualism, meanwhile, helps mitigate language conflict by modeling flexibility...

Anti-Hegemonic Code-Switching: The Case of Odesa Poet Boris Khersonskii, Part II

Immediately after Euromaidan, Khersonskii began to reflect on his own precarious position as a Russophone patriot of Ukraine who had published his poetry primarily in Moscow and St. Petersburg.

Anti-Hegemonic Code-Switching: The Case of Odesa Poet Boris Khersonskii, Part I

In 2018, Boris Khersonskii, Ukraine’s most famous Russian-language poet, wrote on Facebook—in Ukrainian: “My credo is: in Odesa, obstruct the Russian language gently, but oppose boorishness on the part of...

Ukrainian Russophonia: Beyond the "Russian World" Paradigm

As the famous Ukrainian writer Andrey Kurkov pointed out in a June article for "The New Statesman," the atrocities of recent months have made it quite likely that Russian will...

Russia’s War on Ukrainian Farms

The Russian military is deliberately targeting key farming-related assets and facilities with the aim of inflicting short- and long-term harm. Moreover, by blockading the Black and Azov seas, Russia controls...