This event will be hosted fully online. Register for the Zoom meeting.

One of the outcomes of Catherine the Great’s Russo-Turkish War (1768-1774) was the return of the bubonic plague to the Russian Empire. It was the third outbreak during the eighteenth century, but was by far the deadliest that century, reaching as far north as Moscow. The European medical community framed the Russian Empire as a laboratory for neo-Hippocratic “cold” diseases, including tuberculosis, scurvy, and influenza. The arrival of a “hot” disease such as the plague confounded medical expectations and delayed an effective response beyond the imposition of a quarantine along the Ottoman border. In fact, physicians working in Russia even argued that the outbreak was not a “true” plague but rather an unknown disease arriving from North America via the ongoing explorations of the North Pacific. Therefore, it was a cold disease with no connection to the danger on Russia's southern border. By considering the plague of 1771-1772 in light of contemporary medical knowledge, this talk will connect the views of Russia’s climate and its effect on the bodies of imperial subjects to the broader European medical and scientific discussions of the late eighteenth century.

Matthew P. Romaniello is Chair and Professor of History at Weber State University in Utah. He is the author of three books: the forthcoming Europe’s Laboratory: Climate and Health in Eighteenth-Century Russia (Cornell University Press, 2025), and the earlier Enterprising Empires: Russia and Britain in Eighteenth-Century Eurasia (Cambridge University Press, 2019) and The Elusive Empire: Kazan and the Creation of Russia, 1552-1671 (University of Wisconsin Press, 2012). He is the former editor of both Journal of World History and Sibirica: Interdisciplinary Journal of Siberian Studies.

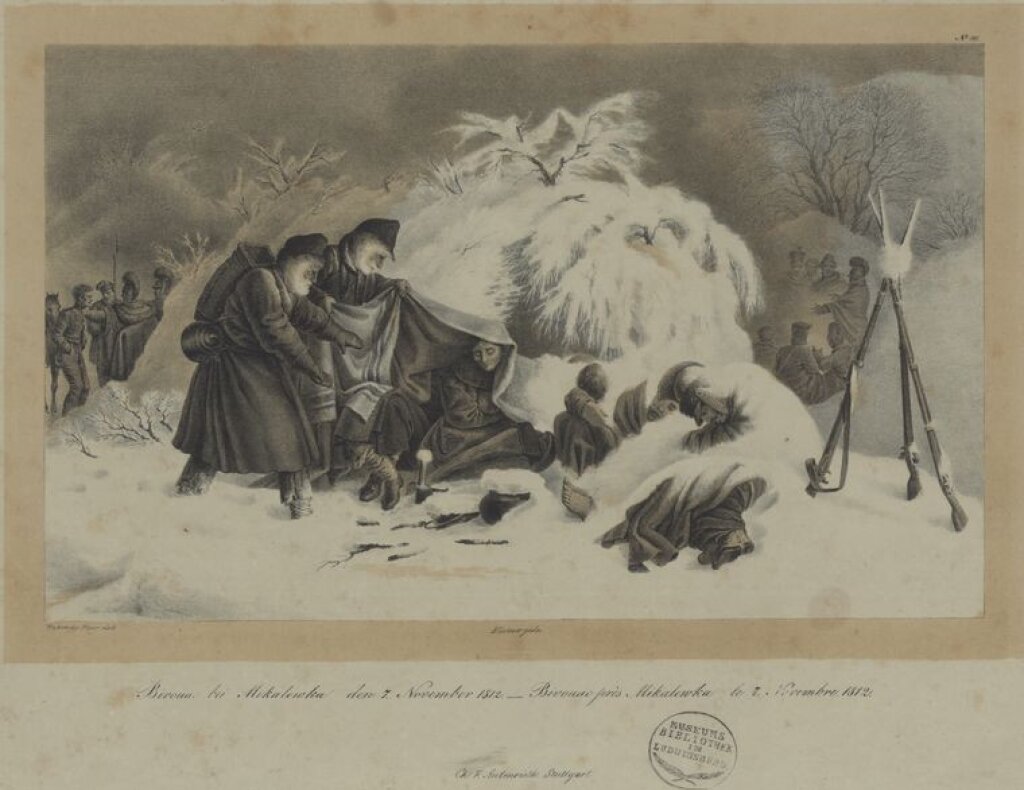

Image: https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/afda0010-c6ce-012f-6722-58d385a7bc34?canvasIndex=0