The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Maria Hristova is an assistant professor in the Department of World Languages and Literatures and head of the Russian Section at Lewis and Clark College. Her research is focused on two main projects: the intersection of gender, sexuality, and religion in contemporary Russian-language women’s writing, and environmental themes in (post-)Soviet literature and film.

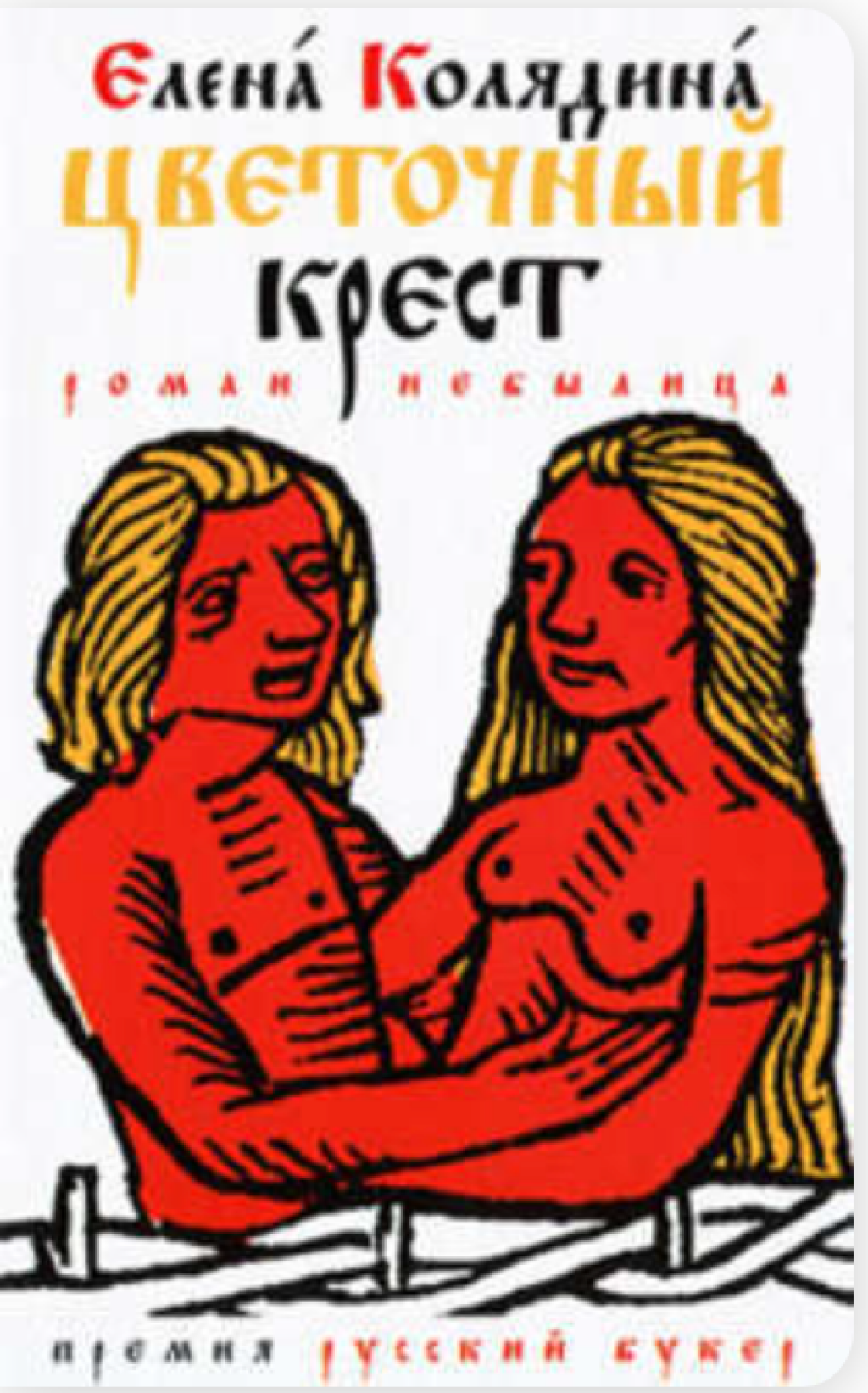

The longer version of the article from which this post is drawn examines one way in which Russian women writers turn to Christian symbols and tropes to imagine and articulate asceticism—the practice of renouncing physical pleasure and material possessions—as an alternative mode of embodiment to the representations of femininity prevalent in contemporary Russian public space. I focus on Tat’iana Mazepina’s travelogue, “Puteshestvie v storonu raia: V Egipet po zemle” (“Traveling to Paradise,” 2012), and Elena Koliadina’s novel Tzvetochnyi krest (The Flower Cross, 2011), two very dissimilar works by authors from different generations that both explicitly engage with aspects of Russian Orthodoxy. Despite the genre differences, the writers’ age gap, and their positioning vis-à-vis Orthodoxy and the Church, both works engage explicitly with asceticism and de-sexualization as empowering modes of female embodiment. In these texts, the female protagonists achieve a moment of transcendence not within the establishment, but in non-urban or marginal locations. Consequently, identity-formation and meaning-creation for these women remain within a larger Orthodox community and cosmology, but they happen outside the direct jurisdiction of religious institutions.

Post-secularism and gender

The use of Christian tropes and narratives by contemporary writers marks their texts as part of the post-secular moment. In the post-Soviet context, this term denotes the ability to discuss, (re)define, and critique religion and to incorporate religious elements in artistic works without fear of official state reprisals. Despite the constantly shifting landscape of women’s involvement and engagement with Orthodoxy and the Church, those seeking to reconcile female religious subjectivity and current Church dogmas—particularly as articulated by reactionary clerics—continue to face difficulties.

Since the late 1990s, a growing number of narratives, including those by Mazepina and Koliadina, explicitly incorporate Orthodox tropes that allow their female protagonists to achieve a meaningful religious experience. The religious turn in Russian women’s writing, with its emphasis on asexual and ascetic embodiment, seems in line with what has come to be termed third-wave feminism, a loose theoretical framework emerging in the 1990s in the West European and North American contexts.

Especially in relation to religious beliefs and practices in non-liberal societies, a number of scholars whose work is informed by this more nuanced understanding of femininity and feminism, such as Saba Mahmood, explore women’s subjectivity and self-expressions that do not align with secular Western ideas of agency and gender equality. Mahmood, for example, demonstrates that women’s choice to inhabit religious norms, such as wearing the veil and abstaining from sexual intercourse, can be a valid expression of free will, even if it does not actively seek to change patriarchal and institutional structures.

Tat’iana Mazepina: asceticism through pilgrimage

Tat’iana Mazepina presents “Traveling to Paradise” as an autobiographical travelogue about her hitchhiking trip through the Middle East. The narrator’s choice to traverse the distance on her own in order to reach the Monastery of St. Catherine, relying on God’s will, places the text within a wider tradition of Christian women recording their pilgrimages. The theme of pilgrimage creates distance between the traveler and the stereotype of the young, mercenary Russian woman who is reduced to her ultrasexualized body, either by choice or by force.

Several episodes throughout the story emphasize that the author is self-conscious about the stereotype of Russian women as “easy,” particularly because the workers at bars and night clubs in the Middle East are often either Russian or East European. The main idea of Mazepina’s travelogue—achieving wisdom and spiritual enrichment in the middle of the desert while remaining part of a religious community—is summarized by the protagonist’s comment on the social condition in contemporary Russia: “the moral and religious foundations in our country were completely destroyed and only now are being restored.” This pronouncement reveals a perceived need to redefine and rebuild the foundations of Russian society, implying that the narrator is part of the process, attempting to articulate an alternative way of being for a young religious woman in contemporary Russia.

Elena Koliadina: asceticism, self-harm, and exile

A very different take on female embodiment and religious experience is presented in Elena Koliadina’s novel The Flower Cross, which was awarded the Russian Booker prize in 2010. The plot is based on the highly fictionalized story of Feodosiia, a young woman burned as a witch in the late seventeenth century in Totma. In the novel, women other than the protagonist are generally depicted negatively, and female bodies and sexuality are described as the cause of all human suffering. Moreover, a Church representative, Father Loggin, believes he can control the protagonist through her body, convincing her to abstain from sex with her husband. Ultimately, though, his behavior misfires and his words inspire Feodosiia to self-circumcise, placing her beyond anyone's sexual control.

The circumcision scene, arguably the most controversial moment in the novel, signifies Feodosiia’s simultaneous personal liberation and portends her religious condemnation. Her actions lead to her exile from her household and town, since permanent self-harm is forbidden by the Church. In other words, subversion of the status quo in the novel occurs through the conflicting acts of total repudiation of the feminine through a deed condemned by the religious authority. The character’s exclusion from the heteronormative group leads her to the woods, where she explores her faith away from Church supervision. However, the manner of this exploration is shown to be an alternative to, rather than a substitute for, the hegemonic system, and does not counteract the misogyny that seems to permeate the novel’s world.

Conclusion

The texts my article examines provide two different views of asceticism as female empowerment. In Mazepina’s travelogue, the protagonist counteracts prevalent images of women as either sexual commodities or housewives by entirely removing herself from her routine. Her adoption of the female pilgrim role allows her to feel connected to a larger, universal community of believers while simultaneously offering her freedom of movement. In Koliadina’s novel, by contrast, self-circumcision— an extreme form of de-sexualization and asceticism—is depicted as subversive and liberating partly because it leads to exile from the home, where sexually active women are contained. However, this "alternative" mode of female embodiment leads, eventually, to death, suggesting there is no space for women as fully realized, God-bearing subjects.

While asceticism can be interpreted as either affirming or subverting established Christian tropes and institutions, both works present female faith and religious practices as conditional on the rejection of female sexuality in favor of ascetic and asexual embodiment.