For those of you not already consumed by fire in the molten pits or, worse, living without wi-fi, there are no more shopping days left before the Mayan Apocalypse. For the long-dead Mayans themselves, this particular doomsday is rather moot, yet it is precisely this overlooked apocalyptic jetlag that brings me to Russia.

One of the many charms about end-of-the-world panic is that it perfectly exemplifies the old leftist slogan, "Think global, act local." Only in movies and comics can the destruction of a planet be shown in a single frame (think Krypton, nuke Alderaan). Otherwise, it's the ultimate world news with a local angle. The Mayan Apocalypse is an excellent vehicle for glocal eschatology; while it's had the mixed blessings of Hollywood's publicity machine, it doesn't really belong to anyone anymore. Why shouldn't Russia be part of the story?

Anyone following the Russian media or Internet knows that this is a big story, even if "man-on-the-street" interviews on Russian television rarely turn up anyone who really believes the world is ending on December 21. Both the government and the Orthodox Church have reassured the country that the Mayan Apocalypse has no basis in reality (although clergy are still quick to remind the faithful that the end is going to come someday). Mostly, it's an excuse for amusing Internet memes and Mayan Apocalypse parties. After all, it's a Friday, and what better way to inaugurate the endless Russian holiday season? It could become a tradition: Doomsday, Western Christmas, New Years, Orthodox Christmas, Old New Years.

As I watch the "news-of-the-weird" Western reporting on Russian apocalypticism, I have the same reaction as when I find out that my friends are reading eBooks on a Kindle or a Nook: where were all of you ten years ago? Russia after the dismantling of the Soviet Union has the dubious honor of being perhaps the only country in the world that is both pre- and post-apocalyptic at the same time. It's not that the world doesn't end, but it never stops ending.

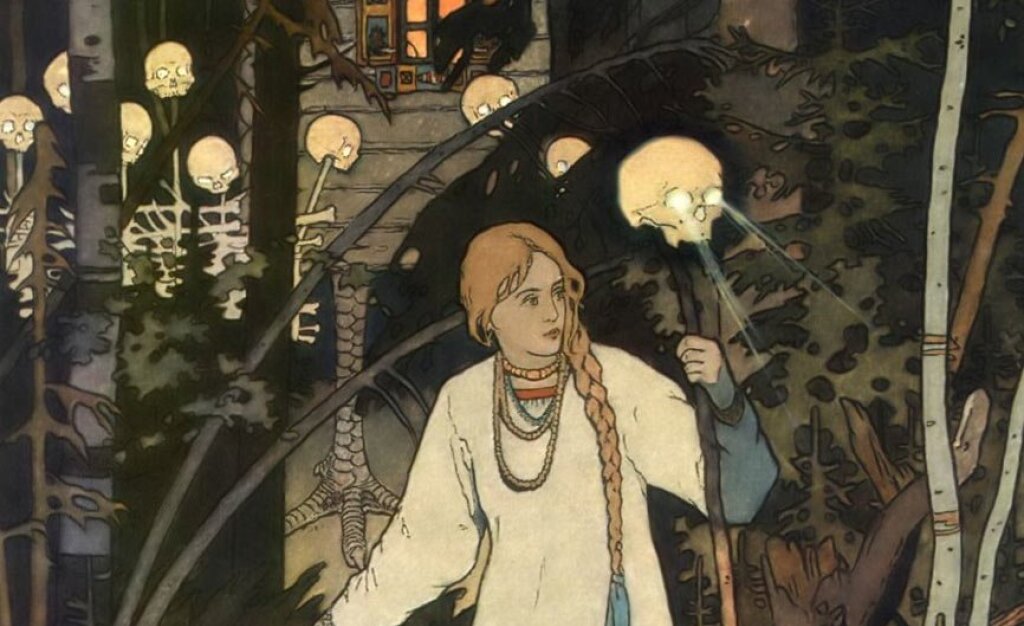

In my own never-ending work (a book manuscript called Catastrophe of the Week: Entertaining the Apocalypse in Today's Russia), I've been paying attention primarily to post-Soviet apocalyptic moments (doomsday sects, financial crises, war and rumors of war). Yet this is a phenomenon that goes way back. When the Mongols invaded Russia in the early thirteenth century, it looked to many like the end of the world. With the benefit of hindsight, it becomes obvious to even the most eschatologically-minded Russians that the Mongol Invasion and the Tatar Yoke were not the Apocalypse, since both good and bad people lived to tell the tale, and the Second Coming did not follow. At best, it was a dress rehearsal for the Apocalypse (dress was casual, dismembering was optional).

These dress rehearsals have repeated themselves with reliable frequency, and became a significant feature of Russian culture in the 1990s. But the contrast between today's Mayan Apocalypse and the media preoccupation with catastrophe just over ten years ago is stunning. The Mayans have done Russia a great service: they have provided an apocalyptic narrative that is so clearly arbitrary, and so thoroughly divorced from Russian cultural traditions, that the entire country can join the Russian-speaking diaspora in turning the apocalypse into carnival. So when we make out traditional toasts (first to our hosts, second to the ladies), we should borrow from the traditions of Russian veterans, and raise a third glass to the dearly departed Mayans, who've shown us today how to stop worrying and learn to love to the end of the world.