We at the Jordan Center stand with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Matthew Handelman is an associate professor of German at Michigan State University and the author of The Mathematical Imagination: On the Origins and Promise of Critical Theory.

Old habits die hard. One especially pernicious “habit” that has resurfaced during the Russian invasion of Ukraine is the claim that Adolf Hitler, the man who led the attempted annihilation of European Jewry, was himself part Jewish. At a May 1 press conference, Russian Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov stated that Ukraine could still harbor Nazi elements even though its president, Voldymyr Zelensky, is Jewish. “I could be wrong, but Hitler, too, had Jewish blood. That [Zelensky is Jewish] doesn’t mean anything at all,” Lavrov claimed. “The wise Jewish people says that the most intense anti-Semites are, as a rule, Jews. ‘Every family has its black sheep,’ as we say in Russian.” These sentiments racialize the issue of Jewishness (as a matter of “Jewish blood”) in the same ways the Nazis did and patronize Jewish people as “wise.” Moreover, even as Lavrov hedged his claims with the phrase “I could be wrong,” his statement participates in the cruel unlogic of antisemitism deployed by the Nazis themselves.

Lavrov’s comment is true and untrue at the same time. It is true in a trivial sense, in that any large group of people is bound to have some members who hate other members of the group or even the whole group itself; there are certainly anti-US citizens of the United States (depending on one’s definition of “anti-US,” of course). The history of the German Jews also contains instances of self-hatred: consider the antisemitic sentiment animating Karl Marx’s “On the Jewish Question” (1844) or the disdain with which many assimilated German Jews looked upon their Eastern European counterparts, the so-called Ostjuden, after the First World War.

At the same time, there is no historical evidence indicating that Hitler’s paternal grandfather, whose name was not included on Hitler’s father’s birth certificate and hence aroused suspicion, was Jewish. Rumors about Hitler’s “Jewish” background began in the 1920s, well before the seizure of power in 1933, and were rekindled in the 1970s by the memoir of Hitler’s personal lawyer, Hans Frank. As historian Ian Kershaw shows, the historical evidence from nineteenth-century Austria demonstrates such claims to be baseless. In Lavrov’s statement, the trivial truth (that Jews can hate Jews) serves to validate the untruth (that “Hitler, too, had Jewish blood”)— with two implications.

At a minimum, Hitler’s “Jewishness” lends credence to claims that Jews were complicit in the Holocaust at the highest levels. It is well-known that the Nazis often forced leaders of Jewish communities to help manage ghettos and organize deportations (the so-called Judenräte)—a fact the Russian Foreign Ministry invoked following the initial backlash to Lavrov’s comments. Artists like Claude Lanzmann and thinkers like Hannah Arendt have wrestled with the moral implications of such forced collaboration in moving and provocative ways.

And yet the claim of Jewish collaboration is an antisemitic strategy used to shift blame from the perpetrators and those who willingly collaborated with the Nazis onto their victims. This type of “thinking” rebrands victims as complicit in the crime perpetrated against them in order to distract observers from the real object at hand: the systematic murder of 6 million people or, as is the case here, Russia’s unprovoked invasion of a sovereign state. Lavrov’s statement creates the false impression that Zelenksy’s Jewishness neither disqualifies him as a Nazi nor exculpates him from abetting Nazis in Ukraine, instead justifying the Russian project of alleged Ukrainian “denazification.”

At a maximum, Hitler’s “Jewishness” would imply that European Jewry brought their own attempted annihilation upon themselves. Another antisemitic tactic of blame-shifting, this line of “thought” underpins what historians like Deborah Lipstadt have called Holocaust or genocide inversion, which turns victims into perpetrators and perpetrators into victims. While Holocaust inversion is a frequent tactic among those who equate Israel with the Nazis, the inversion of victim and perpetrator was a pillar of the Nazis’ own propaganda and mythmaking from the 1920s onward. According to Hitler and his propaganda minister Joseph Goebbels, an international Jewish conspiracy was persecuting an otherwise robust and healthy German people (Volk), having first brought about Germany’s defeat in the First World War and the global economic turmoil of the 1930s.

For example, Hitler justified the boycott of Jewish businesses in April 1933 as “a defensive measure against Jewish atrocity propaganda abroad.” By “propaganda,” Hitler here meant the international outcry to the Enabling Act, which gave him, as Chancellor, the power to rule by decree. “Jewry,” he claimed, “must recognize that a Jewish war against Germany will lead to sharp measures against Jewry in Germany.” Here we see the (un)logic of antisemitism in full force: the victim (“Jewry,” of which the German Jews are a part) compels the perpetrator (the Nazis, now in full control of Germany) to commit the crime (an anti-Jewish boycott). “Those impelled by blind murderous lust,” Max Horkheimer and Theodor W. Adorno wrote in their “Theses on Anti-Semitism” (1944), “have always seen in the victim the pursuer who has driven them to desperate self-defense.” The “reasoning” that turns perpetrator into victim and cold-blooded murder into self-defense belongs to the same ideological complex that, then as now, “justifies” anything from invading other countries to mass murder.

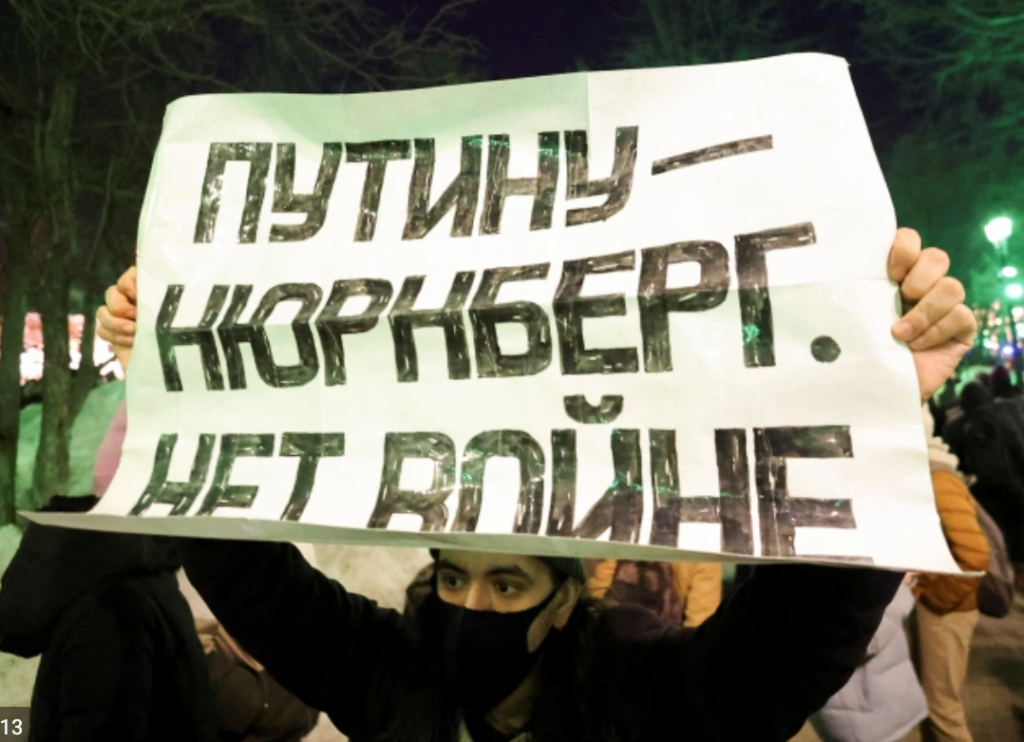

Commentators, including those writing for this blog, have noted that Russia’s invasion of Ukraine under the banner of “denazification” demonstrates the continued relevance of many post-Second-World-War mindsets and vocabularies nearly 80 years later. Lavrov’s comments show that the cruel yet pervasive unlogic of antisemitism, too, remains in effect.