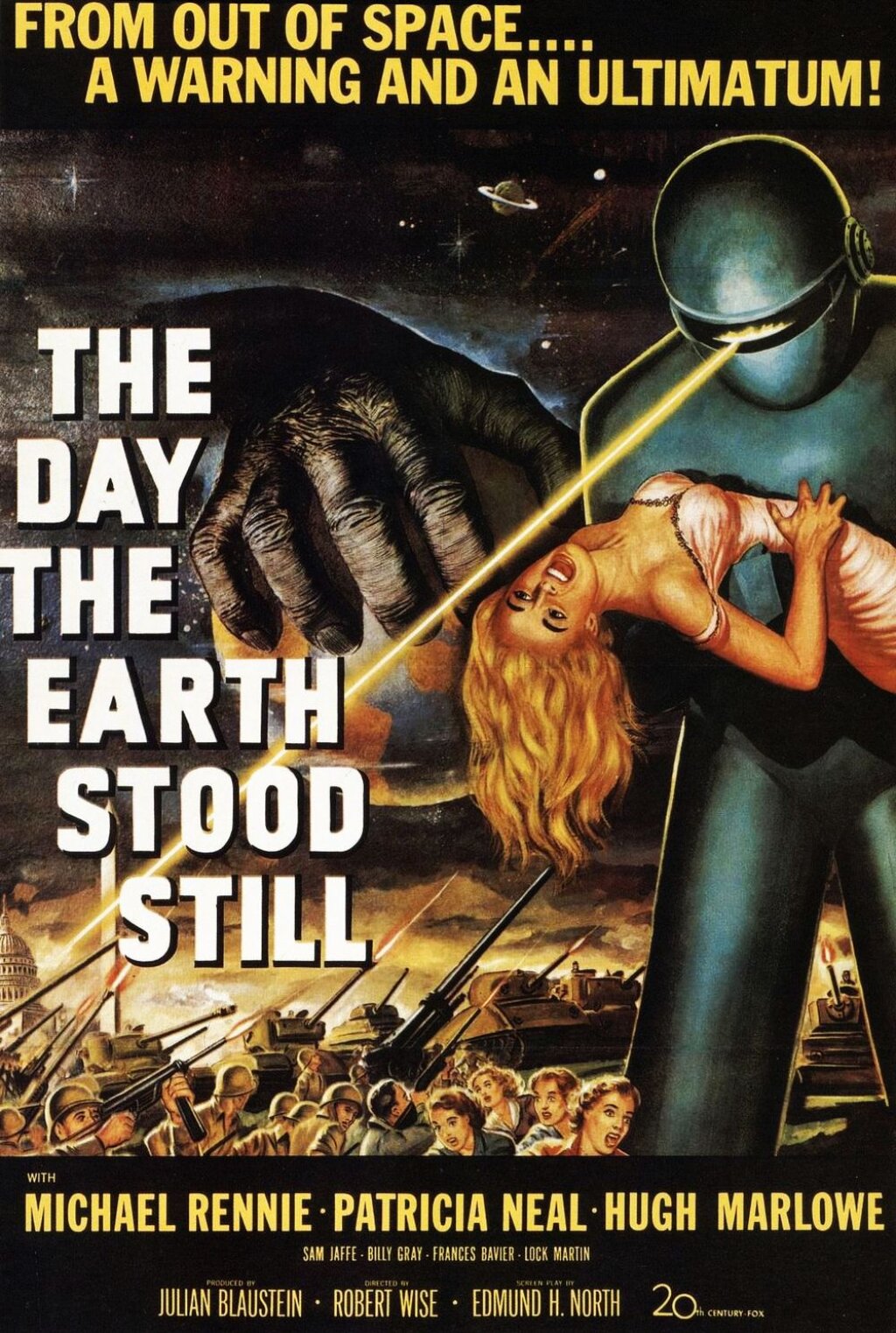

Above: The author with Eduard Limonov in August 2013. Photo by Dondanillo.

Fabrizio Fenghi is an assistant professor of Slavic Studies at Brown. His book It Will Be Fun and Terrifying: Nationalism and Protest in Post-Soviet Russia (University of Wisconsin Press, 2020) focuses on the culture and history of Eduard Limonov’s National Bolshevik Party.

Eduard Limonov (né Savenko) died in a Moscow hospital on the evening of March 17, at the age of 77. According to the website of the “non-registered” radical organization The Other Russia, today’s incarnation of the National Bolshevik Party, which he led, the official cause of death was cancer. Limonov, as he often claimed, would have rather died a violent death, preferably “blown up” by one of his political opponents. And he tried as hard as he could to die young, like a romantic hero. Limonov was an absolute rebel and an absolute contrarian. At times he called himself a hero, at times a loser. And at times he looked like a fool. As many of those who knew him wrote in the past few days, Limonov had never grown old. Or to put it differently, like in the lyrics of a famous song by his beloved Ramones, Limonov didn’t really want to grow up.

(Russian-)American readers mostly remember him as the protagonist at the beginning of his most famous semi-autobiographical novel, Eto ia – Edichka (It’s Me, Eddie, 1979), standing naked on the balcony of the Hotel Winslow at the corner of Madison Avenue and Fifty-fifth Street, eating cabbage soup from a giant pot and shocking “the clerks, secretaries, and managers” looking at him from behind the windows of the surrounding office buildings. The novel portrayed all the misery and humiliation of émigré life, Edichka’s compulsive loneliness and masturbation, his love for the outcasts, and his sexual escapades with both women and strong African American men. Edichka lived on welfare, criticized dissidents for ignoring the fate of millions of Russian immigrants for whom life in the West had turned out to be even more miserable than in the Soviet Union, befriended Americant Trotskyites, and dreamt of a violent world revolution.

In the 1990s, Limonov came back to Russia and co-founded (with the guru of Russian imperialism Aleksand Dugin) the National Bolshevik Party (NBP), with the goal of gathering into a single organization all of Russia’s new outcasts and those whom the market reforms had left behind—communists and fascists, as well as punks, anarchists, metalheads, war veterans, and nonconformist artists. The party and its newspaper Limonka combined the aesthetics of the Russian avant-gardes, Italian Futurism, neo-Nazism, and punk. Limonov and his followers wrote about Jean Genet, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Guy Debord, Herbert Marcuse, and about idols of the far right like Julius Evola, Miguel Serrano, and the general of the White Army Roman Ungern von Sternberg, the “Mad Baron.” For a good part of the 1990s, the NBP remained a sort of political art project that attracted pretty much everyone who had a taste for the radical and the extreme. To use the expression of Alexey Tsvetkov, one of the minds behind it, the National Bolsheviks or natsboly were mostly “thugs who aspired to be poets” and “poets who aspired to be thugs,” who scared the Russian public with terrifying slogans like Zavershim reformy tak—Stalin, Beria, Gulag (“This is how we’ll implement reforms—Stalin, Beria, Gulag!”). In the late 1990s, the natsboly tried to turn some of these scary slogans into reality by organizing an armed revolt in the Altai Mountains. But things did not turn out too well and Limonov ended up spending three years in prison on illegal arms trade charges. When Putin came to power, the natsboly became pioneers of the resistance against his authoritarian rule, in part redeeming themselves in the eyes of the liberal media. With the coalition The Other Russia, the Dissenters’ March, and Strategy 31, the focus of the NBP became advocating for freedom of speech and assembly and protesting human rights abuses, social inequality, and corruption. The natsboly became famous for their peaceful and carefully staged “direct actions” against the government. They also indirectly exerted a certain influence on mainstream politics: the infamous state-sponsored youth movement Nashi, for instance, was thought of as a direct response to the NBP in the wake of the Orange Revolution in Ukraine. Things changed again quite drastically in 2014, when the natsboly, who had historically supported the idea that Russia should take back all the territories formerly belonging to the Soviet Union, supported Putin’s annexation of Crimea and the separatist conflict in Eastern Ukraine. Since then, Limonov became a somewhat more acceptable figure for the Russian establishment and mainstream media. Many in Russia saw this as a betrayal and a sign that he had sold out to the regime.

As Eliot Borenstein points out, Limonov’s legacy is indeed complicated. Perhaps it is not by chance that the NYT whitewashed his memory, given that Limonov’s life and personality cannot be easily boxed into a unidimensional narrative (as the ones that unfortunately the NYT has recently produced when covering Russia). Faced with a similar issue, scholars of Russia have historically tried to compartmentalize his life and work, trying to fit him into one or the other canon: “he was a great writer, but a horrible politician,” or vice versa, “he was not a writer but a media personality and a provocateur, but as a writer he will soon be forgotten,” or again, “his early poetry was great, but everything he did afterwards was despicable.” Paradoxically, Limonov himself did everything he could to be recognized as a writer and at the same time he made sure that his work could not become part of any kind of canon. His novels are intimate, sexual, and violent to the point of being disturbing. His poems are direct, funny, and often very powerful. He violated taboos and challenged the puritanism and conservatism of the Russian literary establishment by portraying homosexual love and desire, as well as the anger of the Russian and Soviet peripheries. And he was a pioneer of Russian counterculture. In this sense, the NBP was Limonov’s main and most accomplished masterpiece, like The Sex Pistols were Malcolm McLaren and Vivienne Westwood’s. Indeed, style and fashion played an important role for Limonov, who back in the 1970s made his way into the Moscow underground by tailoring pants for prominent Russian artists and writers. But, like many punks and rockstars, and perhaps even more so, in his quest for radicalism and destruction Limonov also embraced various forms of hate and bad taste. He befriended and admired war criminals in the former Yugoslavia in the early 1990s and he tried to join forces with true neo-Nazis like the infamous leader of Russian National Unity Aleksandr Barkashov. And both his writing and his politics were not devoid of misogyny, machismo, and prejudice.

For someone who based so much of his work and life on self-fashioning, Limonov’s public persona was not very likable. He was not at all accommodating and he often played the part of the tough guy—but with thick glasses (which he hated) and a slightly high-pitched, almost nagging voice. Sometimes he could be unpleasant. I experienced this intentionally hostile attitude first-hand when I interviewed him in his apartment in Moscow back in 2013 when I started researching the NBP. On that occasion, Limonov played a role that (as I later discovered) he had rehearsed many times in the past. He welcomed me in adidas sweatpants and a sort of souvenir t-shirt with the writing “Cuba, Pearl of the Carribbean.” At the time I was a graduate student at Yale, which he obviously saw as a symbol of academic prestige and Western colonialism, but of course I was also much younger and more inexperienced than he was and I found the idea of talking to him, a famous Russian writer, about my project potentially intimidating. However, during the interview Limonov refused to answer several of my questions and repeated several times—scoffing—that he had no idea of what I was talking about because he “did not go to Yale” and he was a politician and a “man of action” and not an intellectual. As I later discovered, this was a rhetorical device that he often used during interviews with academics—of course by changing the name of the prestigious institution in question (La Sorbonne, Yale, Berkeley, etc.). Even if at the time I thought that this response was quite superficial and almost a bit cliché, what I found redeeming later on in my research was Limonov’s loyalty, support, and sympathy for those who are most vulnerable and disenfranchised. I could appreciate these qualities not just in his writing but through the eyes of the numerous natsboly I talked to while working on my book, all of whom respected him deeply and saw him as a source of inspiration. Limonov had been hostile toward me because he thought I came from a position of privilege (like most of the journalists and academics he interacted with), while he reserved his humanity and support for his young radical followers, who for better or worse were fighting or had been fighting, in certain cases sacrificing pretty much everything they had, for what they believed in. Overall, I could respect that.

Limonov often proclaimed his love for the outcasts and the losers of the world and his hatred for the “masters of life.” In one of his best novels, Podrostok Savenko (The Adolescent Savenko, translated into English as Memoir of a Russian Punk), Limonov’s alter ego is Eddy-baby, a romantic, desperate, and somewhat naïve sixteen-year-old from the working class periphery of Kharkov (or Kharkiv) in Soviet Ukraine in the 1950s with a passion for poetry and organized crime—a sort of Young Werther carrying a straight razor in his pocket. While walking through a sketchy neighborhood in New York City, Edichka declares: “If I were making a revolution I would lean first of all on the people among whom we were walking, people like me — the classless, the criminal, and the vicious. I would locate my headquarters in the toughest neighborhood, associate only with the have-nots.” Throughout his life, the eternal adolescent Limonov remained faithful to his young, angry, and somewhat naïve self, that of Eddy-baby, and to the losers of the world, and brought this energy into his writing and politics. It is ironic that Limonov died at a time of fear of contagion and “social distancing.” What Edichka hated the most about America and neoliberalism was the distance and indifference that he experienced as a poor, marginalized immigrant, which he identified with the words “that’s not my problem.” Edichka’s work and politics were too personal, physical, and almost visceral to be appreciated from afar—they needed to be experienced up-close.