This is Part II in a two-part series. Part I may be found here.

Ekaterina Olson Shipyatsky and Fiona Bell worked as 2019-2020 Fulbright English Teaching Assistants in Ulyanovsk, Russia.

Ekaterina Olson Shipyatsky graduated from Bryn Mawr College in 2019 with a degree in Philosophy, Politics, Economics (PPE). In 2020, she worked as a volunteer translator and researcher for the GuLAG Museum and the Jewish Museum and Tolerance Center in Moscow. She plans to pursue graduate work in the fields of genocide studies, political theory, and interdisciplinary human rights.

Fiona Bell is a literary translator and scholar of Russian literature. Her writing has appeared in Full Stop, Asymptote Journal, The LA Review of Books, and elsewhere. She is from St. Petersburg, Florida, but currently lives in New Haven, Connecticut, where she is earning a PhD in Slavic Languages and Literatures at Yale University.

It seems that today's tech leaders and historical figures like Stalin or Hitler are worshipped for the same traits: "meritocratic" success, innovative thinking, and motivational ability. While some, like our students, may not have had the atrocity education necessary to understand the crimes their heroes committed, others, like the Stalin Center director and other public commentators, presumably know about these atrocities and consider them irrelevant. Both cases present not the simple problem of ahistoricism, but a structurally imposed amorality. This state of affairs is no accident, since capitalism is intentionally structured to divorce moral concerns from the process of innovation.

Such a configuration, however, fails to keep the moral and material consequences of “innovation” at bay. In A Brief History of Neoliberalism, the anthropologist and geographer David Harvey argues that under the current order of neoliberal capitalism, technological innovation is inextricable from “instability, dissolution of social solidarities, environmental degradation, deindustrialization… and the general tendency towards crisis formation within capitalism." The consequences of innovation are political, which means that tech leaders are also political figures. Today, in both established and burgeoning capitalist societies, technological innovators are as powerful as political invaders from past centuries. Thus, the public's obsession with tech leaders should trouble us, whether we observe it among the bros of Silicon Valley or students at a regional Russian university.

Tech leaders have given us little reason to trust them with the political and moral power they wield. Indeed, blind faith in the liberating potential of technological progress actively undermines democracy and income equality. History has proven that faith in Napoleon as a liberator was misguided; even had he successfully conquered Russia, his policies in Europe give little reason to believe he would have subjected feudal Russia to anything like a liberalization. Similarly, American tech leaders prove time and time again that they care little about social and environmental justice. Tesla, to give just one example, is regularly sued for illegal union-busting; now, in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic, Musk is neglecting the health of his plant workers, just as Napoleon abandoned his plague-ridden soldiers in Egypt and Russia.

Young Russians, including those in our classes, are coming to terms with the bleak economic prospects that have resulted from the authoritarian oligarchy cultivated over the last twenty years of Putin’s reign. Some of them turn outward: to the supposedly meritocratic United States and its heroes of upward mobility. Others, however, refuse to buy into these myths.

Unsurprisingly, clapback to the twenty-first century’s tech heroes comes from its quintessential artists: memers. “How do you like this, Elon Musk?” (“Как тебе такое, Илон Маск”) memes circulate on Runet, featuring shoddy “inventions” spotted in Russian daily life. While these memes certainly mock Musk’s penchant for outrageous ideas, they’re also mocking Russian poverty. The humor in these memes is in the comparison of a toilet-seat drink-holder to a Tesla, but it’s also in the absurdity of the idea that Elon Musk would invent something that could improve the living conditions of the man wearing the toilet seat. By invoking Elon Musk’s “eye for innovation” alongside clear emblems of poor living standards, the memers are emphasizing the irony (and futility) of entreating Elon Musk to deliver them from income inequality. These memes undermine Elon Musk’s status as a tech god by invoking him as an apathetic deity. More importantly, they undermine the myth of the meritocrat who leads others out of systematic inequality.

In 2019, a group of Krasnodar entrepreneurs created a video inviting Elon Musk to their Small Business Forum. Full of visual and musical references to Soviet-era school performances, the video sustains a tone of over-the-top reverence that ultimately marks it as parody. Yet the entrepreneurs’ invitation isn’t a joke. In this video, they evoke the tension between their sincere need for economic growth and their absurd position of having to pray to a negligent god for help.

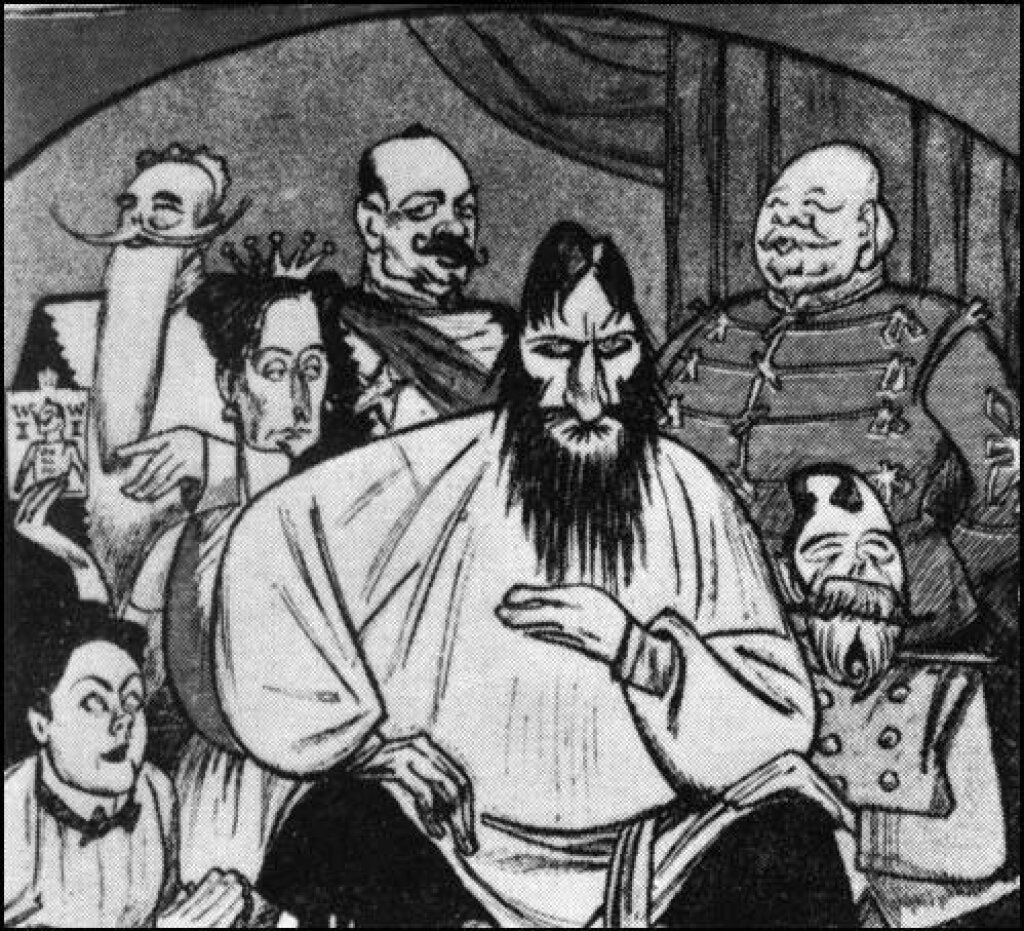

Both the memers and the Krasnodar entrepreneurs are engaged in the project of undermining Elon Musk’s hero status, of making him pedestrian (пошлый). It’s tempting to dismiss these memes as displays of powerlessness in the face of Russian income inequality or global capitalism. However, these pieces are part of a long history of works undermining the myths of “great” but insidious men.

In War and Peace, for example, Tolstoy endows Andrei and Pierre with a common ailment of their time: Napoleon fever in order to critique societal worship of Napoleon. When Andrei encounters his hero while dying on the battlefield, his reverence suddenly dissolves: “He knew it was Napoleon — his hero — but at that moment Napoleon seemed to him such a small insignificant creature compared with what was passing now between himself and that lofty infinite sky with the clouds flying over it” (“Он знал, что это был Наполеон — его герой, но в эту минуту Наполеон казался ему столь маленьким, ничтожным человеком в сравнении с тем, что происходило теперь между его душой и этим высоким, бесконечным небом с бегущими по нем облаками”). In addition to tracing Pierre’s arc from worship of Napoleon to disdain, Tolstoy invites Napoleon himself into the novel’s cast of characters. In chapters where the leader appears, the author uses third-person omniscient narration to emphasize his narcissism and banality (пошлость).

Tolstoy's magnum opus provided a template for future takedowns of popular heroes in later Russian novels. Vasily Grossman’s Life and Fate and Anatolii Rybakov’s Children of the Arbat trilogy, both set during the Great Patriotic War, imagined the similarly pathetic inner monologues of Hitler and Stalin. In Life and Fate, Hitler laments the loss of his “genius” as Germany’s armed forces begin to wane: “But if the power of the armed forces and the Reich wavered for even a moment, then his wisdom began to seem tarnished, his genius vanished” (“Но едва начинала колебаться мощь Новой Германий и ее вооруженных сил, меркла его мудрость, он терял свою Гениальность”). Rybakov’s Stalin, meanwhile, is frustrated by the tension between his genius and a world that cannot comprehend it: “But, as always, when HE demonstrated his exceptionalism, he was overwhelmed by a sharp feeling of loneliness. They stand and clap, but they don’t love him, they are afraid of him, that’s why they stand and clap” (“Но, как всегда, когда ОН демонстрировал свою исключительность, им овладевало острое чувство одиночества. Они встают и рукоплещут, но они не любят его, они его боятся, потому встают и рукоплещут”). As the protagonists lose control, they begin relating themselves to Napoleon, a “great man” toppled by external events. Their desperate comparisons seem absurd and even petty to the reader.

In their historical fiction, Tolstoy, Grossman, and Rybakov undermine the “great man” myth of history. Their descendants — those exposing the banality of today’s “great men” — are arguably the memelords of Runet. However, since meme creators are, by definition, at least somewhat anonymous, it’s more difficult to understand their motives as compared to those of the novelists. Moreover, memes can host a variety of meanings. The Krasnodar entrepreneurs’ music video, the Stalin-Google poster, and the Elon Musk icon memes all acknowledge the power and influence of American tech giants, while also providing tongue-in-cheek commentary on their danger, their banality, and the danger of their banality. These indeterminate, Janus-faced memes powerfully unmask the insidious nature of Silicon Valley tech hero worship, but only if the viewer is already clued in to the dark side of their power.

By invoking the “great man” myth, the meme-creator forces viewers to reckon with their own fundamentally emotional relationships to these heroes. Hero-worship is, after all, a type of romance: a yearning for greatness, a hope in the individual’s ability — one’s own ability! — to rise above circumstance. What’s born from emotion can only be destroyed by emotion. Art, in its ability to inspire pity and bemusement, is the best tool for the job. Beyond their critical messages, memes formally challenge the concept of art as the work of a lone genius. Anonymously created and community sourced, these Russian memes work on two levels — formally and thematically — to undercut myths of individual greatness. As near-daily news articles expose American tech leaders’ unethical business practices and shifts into neoconservativism, we are more in need than ever of creative means for limiting their power. Maybe Russian memers can show us the way.