Stefan B. Kirmse is a Senior Research Fellow at the Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) in Berlin and a specialist in the intersection of cultural anthropology, history, and “law and society” research. His most recent monograph, The Lawful Empire. Legal Change and Cultural Diversity in Late Imperial Russia appeared with Cambridge UP in 2019.

This post derives from his detailed analysis of the Kutaisi Trial in the Central Asian Survey, published in 2024.

This is Part I in a two-part series; Part II will appear on Thursday, 4/17.

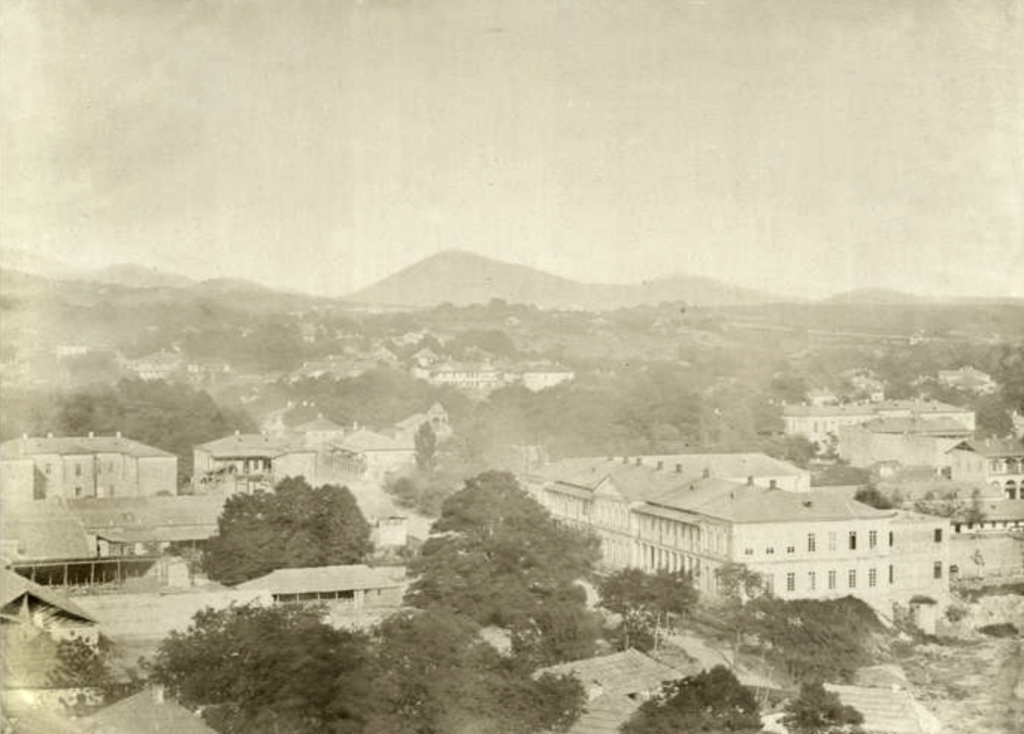

In March 1879, in the Georgian city of Kutaisi, then part of the Russian Empire, nine Jewish men stood trial for allegedly killing a Christian child. As in other cases of blood libel in world history, the men were falsely accused of using the victim’s blood for religious rituals. But unlike in most other cases, the court acquitted all defendants.

How did this accusation come about in a part of the Caucasus where Jews, Christians, and Muslims had lived together for centuries? And why were the accused acquitted?

Some will read the case as a familiar story about antisemitism. For others, it will be about Russian colonialism in the Caucasus, and its legal and cultural repercussions. A third group might argue that the case is not about cultural difference at all and that it tells us more about social and economic injustice.

Further, the Kutaisi trial could be explored in terms of transregional connectivity: the effect of similar cases nearby and international mobilization. All of these perspectives are valid. As a historian of the Russian Empire with a focus on law and cultural diversity, however, I find that the case highlights that, even under autocracy, religious minorities and their liberal defenders had room to maneuver.

The History of Blood Libel

By the mid-nineteenth century, blood libel was only beginning to make a mark on Russian public discourse. Earlier cases had all taken place before the emergence of an independent judiciary, created by the Judicial Reform (1864). There had been no public trials or adversarial court procedure. Thus there existed neither the institutions nor the public discourse that would accompany the Kutaisi blood libel, or later cases such as the famous Beilis Affair in Kiev (1911-1913).

Kutaisi was not the first instance of blood libel in Georgia. In the Surami case (1850-54), only 40 miles from the scene of the crime in 1878, seven Georgian Jewish men were falsely accused of the ritual murder of a Georgian Christian boy. Although there was no evidence against them, local law enforcement and the Imperial Senate still decided to exile them for life. This Surami accusation and conviction left an indelible mark on the public, with anti-Jewish attacks persisting over the decades that followed. Riots against Jews continued to shake Kutaisi, Tiflis, and Surami in the 1860s and 1870s.

There is very little literature on the Kutaisi case, which is striking because the transcript of the trial was published in Russian as early as 1879. A hundred years later, the organization of Georgian Jews in Israel produced Hebrew and German translations. This material is framed in a way that differs from the classic narrative on blood libel, namely its use and manipulation by the authorities, with the editor Gershon Megrelishvili stressing the importance of the reformed courts and the ultimate acquittal.

Some historians have argued that framing Russia’s role in terms of a mediator or even defender of Georgian Jews is little more than a hypocritical justification of colonialism. The Kutaisi case, however, shows all actor groups, including ‘the Russians’, playing multiple roles in this complex story.

A Mysterious Death

In April 1878, 7-year-old Sarra Modebadze was found dead by a stone wall. The body lay about 1.5 miles from the village of Perevisa, where she had disappeared two days earlier.

The girl’s father, Iosif Modebadze, quickly expressed the suspicion that Jews from the small town of Sachkhere, which had a large Jewish population, had kidnapped his daughter. In court, he later testified:

I’d heard that Yids [uriebi] needed Christian blood and remembered that something similar had happened in Surami.

There were no obvious signs of violence on the girl’s body. Yet the family did not believe her death had been an accident, especially since two groups of Jewish men had been seen in the village around the time of her disappearance. The men had made a lot of noise, carrying chickens, geese, and a little goat on their horses. At least two witnesses also claimed to have heard a child’s voice among them. And thus, to the villagers, the case seemed clear: the Jewish men had abducted the girl and later dumped the body.

Antisemitic attacks started shortly after the body’s discovery, leading the Jewish community to turn to the viceroy (and tsar’s brother) in Tiflis for help. They explained that the girl’s family had mobilized false witnesses. And indeed, relying on dubious testimony, the prosecutor of Kutaisi Circuit Court decided to arrest nine suspects and press charges, asserting that the Sachkhere Jews had “in all likelihood” killed Sarra Modebadze. Meanwhile, the Russian governor of Kutaisi Province explained to the viceroy’s administration that the Christian Georgians’ fury toward the Jews was “completely justified” since the latter had surely murdered the girl.

Yet the head of the viceroy’s administration remained skeptical. He found the evidence used by the Kutaisi court investigator used as grounds for the arrests “completely unconvincing.” His concern, however, was political rather than judicial. A release of the prisoners could lead to accusations against the authorities and, from there, further attacks on the Jews. Only a public trial could dispel antisemitic prejudice, and the viceroy, who took a personal interest in the matter, agreed.