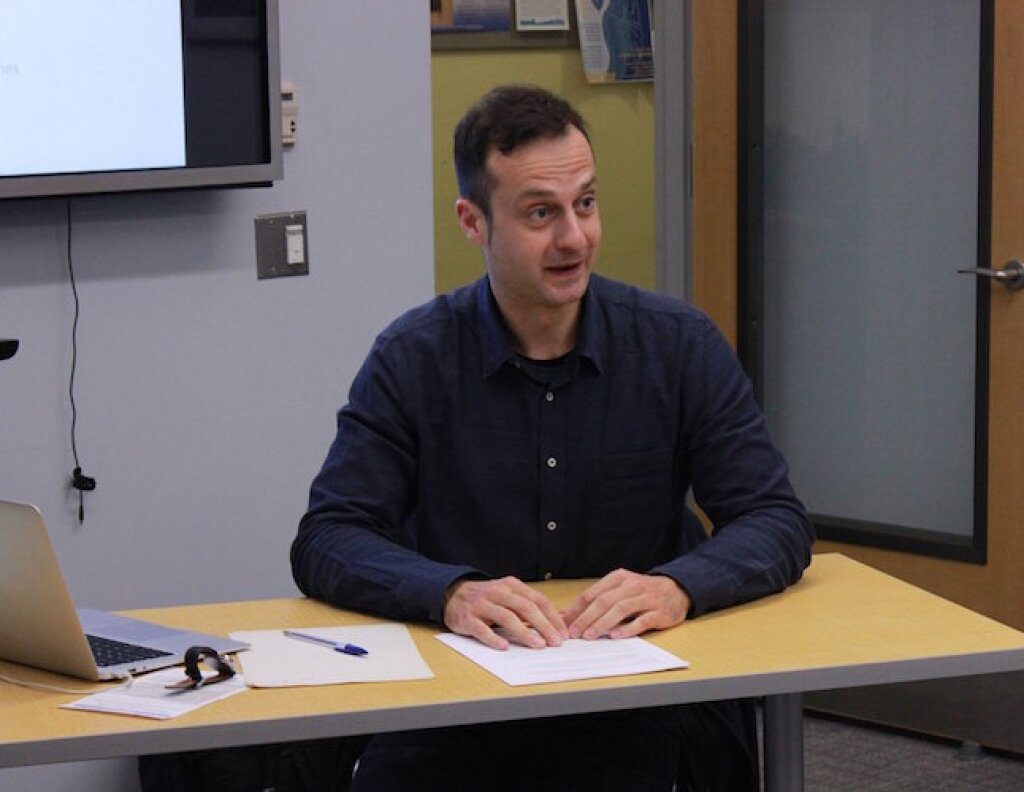

Stefan B. Kirmse is a Senior Research Fellow at the Leibniz-Zentrum Moderner Orient (ZMO) in Berlin and a specialist in the intersection of cultural anthropology, history, and “law and society” research. His most recent monograph, The Lawful Empire. Legal Change and Cultural Diversity in Late Imperial Russia appeared with Cambridge UP in 2019.

This post derives from his detailed analysis of the Kutaisi Trial in the Central Asian Survey, published in 2024.

This is Part II in a two-part series; Part I may be found here.

The Kutaisi Trial

Eleven months after Sarra Modebadze’s death, in March 1879, nine Jewish men stood trial at the Kutaisi Circuit Court. Various newspapers reported from the courtroom, including Kavkaz and the Tiflisskii vestnik, the Georgian-language Droeba, the Russian- and Hebrew-language Jewish papers Rassvet from St Petersburg and Ha-Melitz from Odessa.

In Droeba, the Georgian editor Sergei Meskhi reported with consternation that the belief that Jews kidnapped Christian children for their blood was locally entrenched even among educated people. Another conviction, he added, was that Jewish financial resources would ensure an acquittal. Clearly, antisemitism had become a powerful force.

While the formal charge was abduction resulting in death, the prosecutor explained that the body had been “dumped during the night of the Jewish Passover,” a wink and a nod at the blood accusation. Virtually all newspapers framed the trial in these or similar terms.

This framing also helped the accused to build a transregional support network. They mobilised Aaron Eligulashvili, the most influential Jewish merchant in Kutaisi, who travelled to St. Petersburg and, through local contacts, found the defense lawyer Petr Aleksandrov, who had only just successfully defended the Russian revolutionary Vera Zasulich. Eligulashvili hired Lev Kupernik as a second (Jewish-born) lawyer from Moscow and Mose Kikodze, an experienced (Christian) Georgian lawyer from Kutaisi.

The prosecutors’ case was weak, as numerous witnesses contradicted one another. In a speech that lasted several hours, the defense team focused on exposing the unlawfulness of statements for which people had clearly perjured themselves. Aleksandrov scolded the prosecutors for their poor work:

This case will show Russian court investigators that they should not […] succumb to perjury and slander but be critical of the facts and review them.

To prove the unlawfulness of testimony, the defense relied on various forms of expertise: they used a topographical map of the location in question, showing distances and elevation, combined with testimony on where and when the girl had last been seen alive. As a result, they were able to show that Sarra Modebadze could never have been found by the Jewish men, but instead had taken a different route to go home—where she got lost in the heavy fog, took a wrong turn, and tragically died from cold and exhaustion. They also had a doctor confirm that the body could never have been as unscathed as it was if the girl had really been stuffed into a saddle bag and taken on the two-hour journey to Sachkhere, as the prosecution insisted.

The defense’s approach was rhetorically refined and patronizing towards the state prosecutors—and it worked. The court acquitted all defendants, a decision met with sustained applause in the courtroom.

While the Kutaisi prosecutor would not acknowledge the weakness of his argument and lodged an appeal with the Tiflis Judicial Chamber, the central prosecutor would not play along. The Chamber made the link to the blood accusation explicit by disqualifying those who believed in it as witnesses: “You cannot rely on the words of people who testify […] under the impression of the prejudice that Jews make use of Christian blood.” Thus, with no evidence other than that tainted by antisemitic prejudice, the case had no lawful basis, and the Chamber refused to press charges.

But why was the blood accusation so entrenched to begin with? What led the local Christians to give false testimony? I would suggest three main reasons.

The first is the Surami precedent, tied into Russian colonialism, which resulted in a false conviction and made the religious accusation seem real, causing numerous anti-Jewish riots. These domino effects were closely tied into the second reason, the centrality of hearsay. Rumors were the “fake news” of old, and bad rumours in particular traveled fast. The third reason is socioeconomic: before the Emancipation Reform (1861), most Georgian Jews had been manorial serfs; and even after the reform, they remained dependent on their former landlords. Without access to land, their only choice for a living was trade, which made them vulnerable to accusations of “exploiting’” the Christians. Blood libel was thus facilitated, even made possible, by a more general antisemitism related to the social transformations of nineteenth-century imperial society.

The Kutaisi Trial as a Milestone

For the first time in the history of blood libel in Russia, the accused were acquitted for good, in open court.

While most research on blood libel in Russia has stressed the authorities’ influence over the judiciary and their role in stirring up intercultural hatred, the Kutaisi case paints a more complex picture. Tragic accidents could indeed be manipulated by state actors in the 1870s, when antisemitism was becoming ever more virulent across the empire. Yet the accused took up the fight in the recently reformed court system and came to be aided by liberal jurists.

What about Russian colonialism? Russia had exported antisemitism, one is tempted to conclude, not least because we do not know of any comparable cases of blood libel in Georgia prior to Russian colonization. But this explanation is too simple. In Russia proper, blood libel was also mostly unknown before the nineteenth century, when it turned into a broad, transregional phenomenon.

Further, the Kutaisi case shows Russian actors in various roles. A Russian governor and regional court officials happily jumped on the antisemitic bandwagon. But they also met with formidable Russian opposition: from the defense lawyers and the prosecutors of the Judicial Chamber, and from the viceroy and his administration. Kutaisi was a far cry from Surami. By the late 1870s, colonialism had not only strengthened antisemitism but also delivered some of the tools to fight it, notably an independent judiciary and a diverse press and public sphere. It had also created ever more connections for the Georgian Jews to Ashkenazi Jews elsewhere in the empire, whose help proved crucial to winning the case.

The acquittal did not put an end to local antagonism. Seen as illegitimate, it was soon followed by more antisemitic assaults. And yet, in the six years after the trial, the Jewish population would still double in Kutaisi Province, from around 3,500 in 1880 to 7,000 in 1886.

To some, the acquittal was evidence that Kutaisi was a safe place for Jews—and may have helped this influx. Either way, the growth underlined that, however difficult and traumatic the experience of blood libel might have been, the Georgian Jewish population had no intention of leaving. That their numbers are very small now is a product of the Soviet and especially post-Soviet eras: many local Jews left for Israel in the early 1990s.