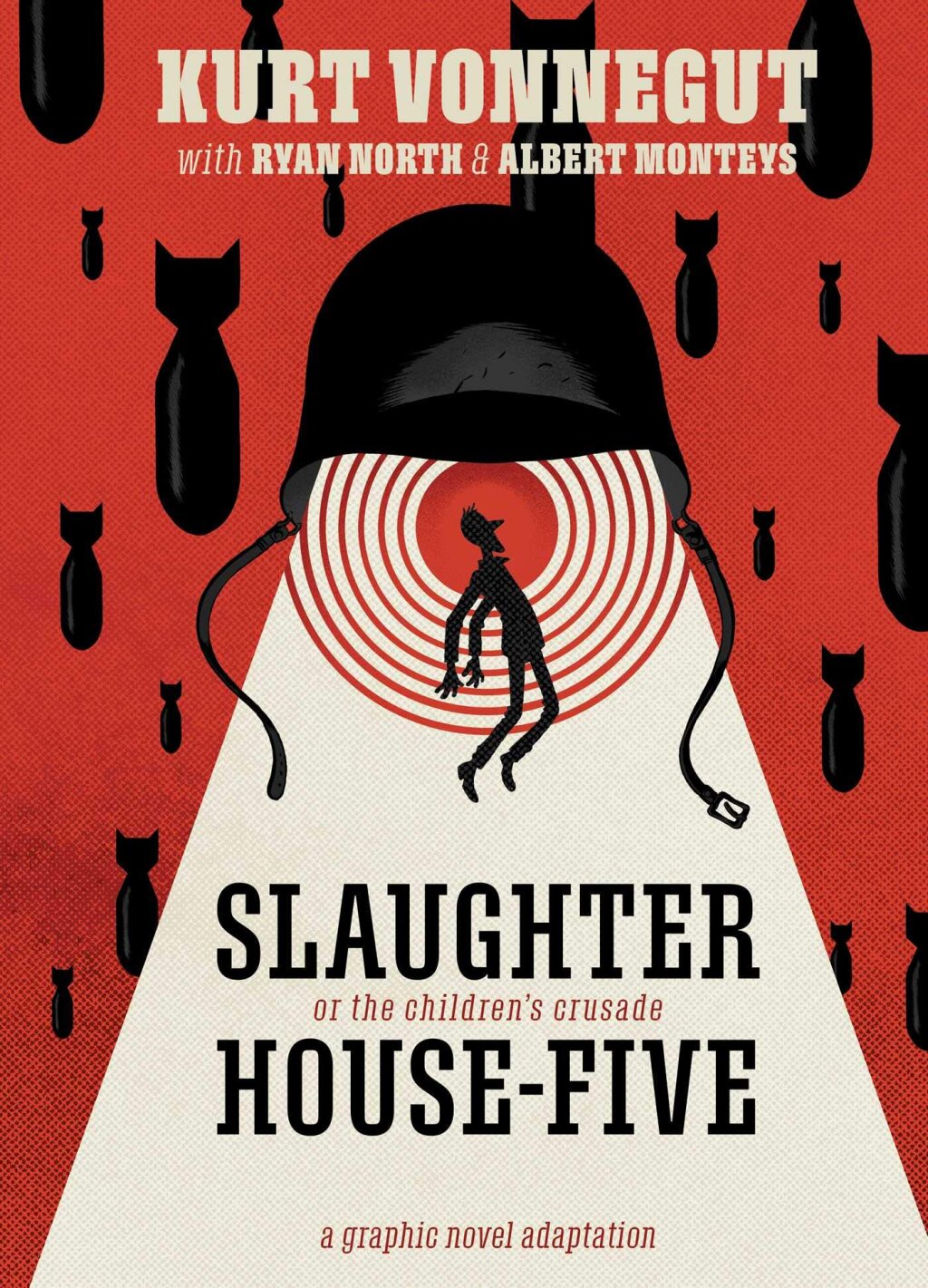

Above: Sections of Russia’s Nord Stream 2 pipeline being connected in the Baltic Sea.

Kyle Fowler is a PhD candidate at George Mason University's Schar School of Policy and Government. His research focuses on the political drivers of Russian oil, gas, and nuclear power exports.

Russia’s Nord Stream 2 natural gas pipeline to Germany has drawn fierce criticism from Washington and split opinions in Europe. The project’s detractors focus on two criticisms: that it will remove one of the few geopolitical tools Ukraine has vis-à-vis Russia, and that it will make Germany and Europe subject to Russian political coercion. However, while Ukraine will almost certainly be worse off as a result of the project, there is reason to believe Russia’s behavior toward Germany will not mirror its relationship with Ukraine, but that, instead, Germany’s position may be strengthened by the new pipeline.

Although petroleum pipelines often strike observers as fostering the dependency of the customer state on its supplier, the oil supply relationship is often characterized by interdependence rather than straight dependence. In the case of former Soviet-bloc states, a robust pipeline network allows them to receive oil and gas from Russia while placing them in the middle of the Russian energy supply network to Western Europe, creating interdependency in the region. Specifically, just as Ukraine, Moldova, and Belarus exited the Soviet Union dependent on Russia for petroleum supply, Russia depends on them for continued supply to its Western European customers and the revenue that supply provides.

This interdependency makes any kind of supply manipulation a costly strategy for Russia. Energy revenues underpin the Russian economy, with petroleum exports accounting for roughly $205B in 2019, more than half of Russia’s overall export revenue. Beyond the short-term loss of revenue associated with supply withdrawal is a potentially more serious reputational risk: if other prospective customers see Russian petroleum providers as subject to Moscow’s geopolitical whims, they may be less likely to pursue Russian oil and gas supply in the future, harming Russia’s long-term economic outlook. Russian gas conglomerate Gazprom actively seeks to curb this perception, often issuing statements assuring the public that Gazprom is a reliable supplier.

Gazprom’s withdrawal of gas supply to Ukraine in 2006, an incident often framed as being driven by geopolitics rather than economics, illustrates the constraints this arrangement places on Moscow and the obstacles to using gas supply in a coercive manner. When Ukraine was unable to meet Gazprom’s price demands, Gazprom halted supply to Ukraine. But since gas still had to flow through Ukraine’s pipelines to Western European customers, Ukraine withdrew from this lowered volume of gas, resulting in shortfalls reported in France, Germany, Italy, and Poland.

Regardless of whether the withdrawal was political or economic in nature, Ukraine’s role in the pipeline network prevented Moscow from being able to effectively localize the withdrawal to its intended target, likely shortening the duration of the shutoff. This element of Ukrainian leverage over gas supply allowed it to avoid the full brunt of Moscow’s intended punishment.

Russia has long sought to diversify its supply routes, completing the first Nord Stream pipeline to Germany in 2011, and recently beginning to send gas through Turkey via the TurkStream pipeline. Both Nord Stream and TurkStream are explicitly justified based on their more reliable supply to Europe, compared to the “older,” “less reliable” system that runs through Ukraine.

Whereas Ukraine currently controls a portion of Russia’s gas supply to Europe, the completion of Nord Stream 2 will ensure that Russia is able to serve European customers without relying on Ukraine at all. Bypassing Ukraine, whether for political or economic reasons (and both likely play a role in Moscow’s decision-making), will reduce Kyiv’s leverage over Moscow.

While critics of the Nord Stream 2 project are correct to note that the project will harm Ukraine’s interests, they also expect that deepening energy linkages between Russia and Germany will make Germany, and possibly even Europe more generally, subject to the same attempts at political coercion as Ukraine was before. These fears are rooted in a history of withdrawals in Ukraine and other former Soviet countries, but there are two reasons to doubt the likelihood of Moscow engaging in such a strategy.

First, the Nord Stream 1 pipeline has been operating since 2011. During the ensuing decade, Russia has not withdrawn supplies once, even during periods of heightened political tension such as in the wake of Sergei Skripal's poisoning. While Moscow appears to see energy withdrawal as a viable geopolitical tool with Ukraine and others in the post-Soviet sphere, it appears reluctant to deploy this strategy in Western Europe.

Second, Germany and other Western European customers pay market rates for their Russian supply, whereas Russian oil and gas relationships in the post-Soviet sphere have been premised on below-market rates and growing debt to Moscow. Even if the withdrawals have been driven by geopolitical concerns, the presence of debt or a gap between current and market rates allows Moscow to use an economic, rather than geopolitical, justification for withdrawing supply.

Moreover, the Ukraine- and Germany-focused criticisms of the pipeline are mutually inconsistent. Observers portray Moscow's ability to bypass Ukraine for westward gas supply as a blow to Kyiv's geopolitical toolkit, yet treat further linkages between Russia and Germany as tools for Moscow to use against Berlin. But if the Soyuz and Brotherhood pipelines do indeed grant Ukraine a degree of leverage over Moscow due to their role in the Russian gas network, Nord Stream 2 should confer similar benefits on Germany.

As a result of Nord Stream 2’s completion, Russia will trade its interdependency with Ukraine for interdependency with Germany. However, it is unclear that Moscow would wield its relationship with Berlin in the same way that it conducts itself with Kyiv, and the benefits Ukraine currently enjoys as a result of its role in gas transmission should also accrue to Germany. Therefore, while concerns about the Nord Stream 2 project lessening Ukraine’s leverage with Russia are justified, anxieties about growing German and European reliance on Russia may be overblown.