The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

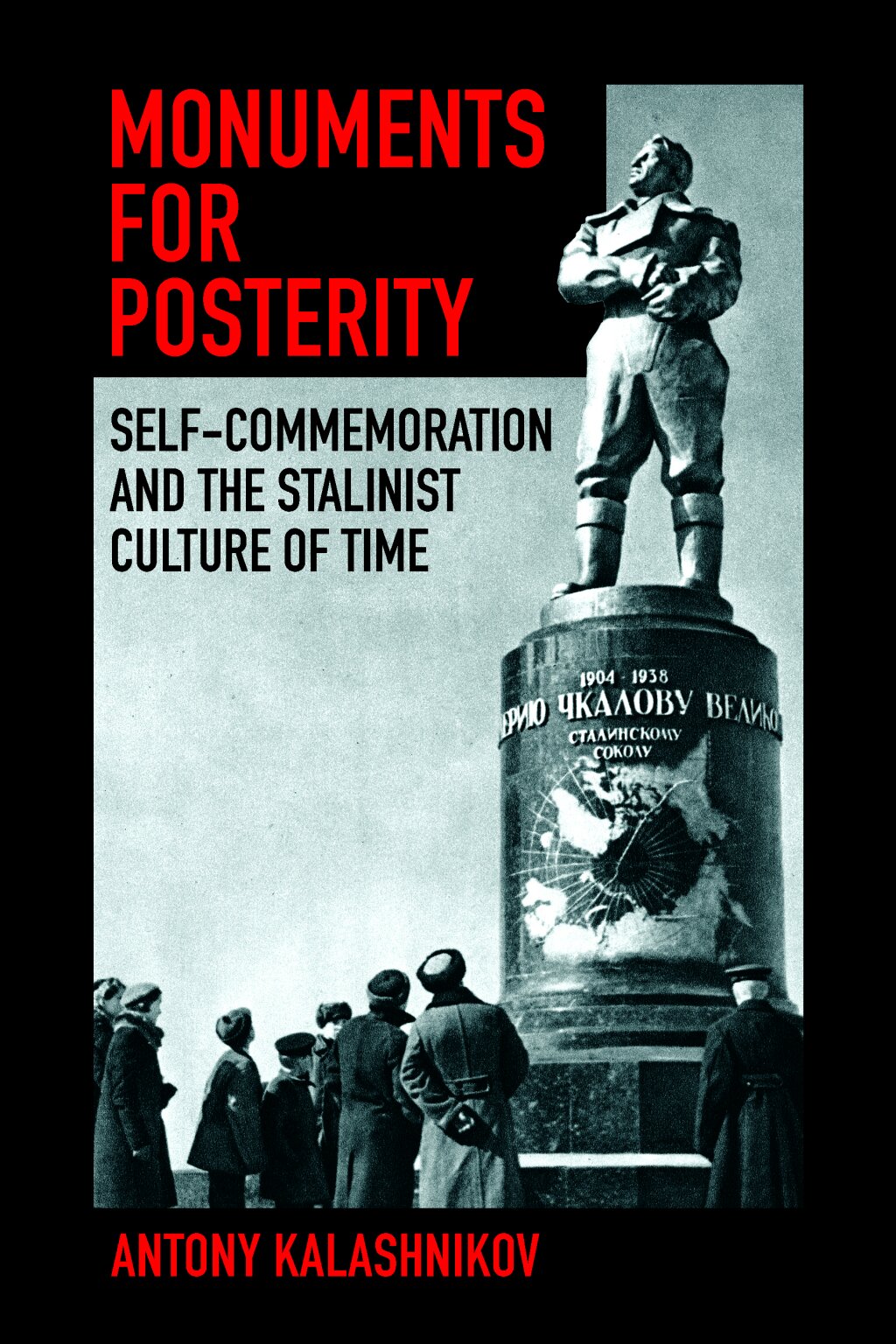

This week, the blog will be running a three-part series of excerpts from Antony Kalashnikov's new book, Monuments for Posterity: Self-Commemoration and the Stalinist Culture of Time, out in April from Cornell University Press. This is Part III. Part I can be found here and Part II here.

Antony Kalashnikov is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alberta (Canada), working on Soviet cultural history.

Stalinist architects consciously designed grand thoroughfares, resplendent metro stations, stately boulevards, and towering high-rises to “immortalize the glorious Stalin era,” in perpetuity. Aesthetically, monument-builders opted for a supposedly timeless, traditional style to ensure that their creations always remained understandable to posterity. Yet by itself, neo-classical Stalinist architecture risked blending in with earlier revivalism. To distinguish their creations as specifically “Stalinist”, monument-builders embellished their creations with art and sculpture, overlayed with contemporary props and epigraphy. Intriguingly, therefore, this artistic suffusion – typically disparaged as an “architecture of excess” – in fact stemmed (at least in part) from the artistic problems of designing everlasting monuments, rather than from an innate totalitarian extravagance.

Synthesis - the practice of uniting architects, artists, and sculptors in concept development and design - was a general feature of Stalinist artistic practice, but it offered unique advantages for crafting monuments that would remain distinctive and eye-catching for future generations. As the preeminent art historian of the time David Arkin stated, “the synthetic unification of art is necessary for the most complete, comprehensive coverage and realistic representation of an artistic idea, with a large field of action [throughout] time.” By means of figurative representations and epigraphy, synthetic monuments could evoke the specificity of the Stalinist era on the canvas of a powerful, timeless, but ultimately indistinctive neo-classical architecture.

These precepts were already reflected in the design of one of the earliest Stalinist monuments – the ultimately uncompleted Palace of Soviets. The gargantuan palace was to overflow with murals, mosaics, sculptures, and other decorations, and these were employed specifically as solutions to the problem of indistinctiveness, without which the building would remain only a “symphony of mute stone.” As the chief architect Boris Iofan attested, it was the “sculptural groups and bas-reliefs [that would] reveal the Palace of the Soviets to be… a monument of the Stalin era.” Art historian Boris Ternovets, referring to the several kilometers (sic) of planned sculptural friezes around the base of the Palace of the Soviets, waxed lyrical: “in this monumental chronicle [the sculptor] can tell of the epic events of the Lenin-Stalin epoch.” He envisioned a narrative recounting of key historical events, which would be “full of internal meaning, unpacking the deep ideational content of the monument [and] the worldview of its epoch.” The compositional approach was soon transposed to all monumental creations of the period.

Nevertheless, the semantic capacity of even the most self-consciously mimetic art was itself circumscribed. After all, sculpture, frescoes, and mosaics could never match the level of detail afforded even by easel painting (to say nothing of the written word). Furthermore, these were traditional mediums and their execution also tended toward classical archetypes. Working within these limitations, one way to underscore the provenance of Stalinist synthetic art was through the liberal use of contemporary props (attributy). These included representations of clothing, power tools, vehicles, weaponry, and other objects particular to the time, which were expected to distinguish the artistic embellishments of Stalinist monuments as specifically Stalinist, in the centuries to come.

The All-Union Committee for Arts Affairs, which commissioned most sculptural works in this period, frequently recommended integrating such props into monument designs. For example, in 1939 its council of experts reviewed the design of a memorial plaque dedicated to the much-celebrated test pilot Valerii Chkalov. One council member, the sculptor Dmitrii Tsaplin, suggested shaping the plaque in the form of an airplane. “Even if time erases [the inscription], they will still see the silhouette and will learn who Chkalov was.” Nearly a decade later, in turn, the council discussing the pedestal for his sculptural monument similarly agreed that Chkalov’s achievements must be somehow evoked visually on it, either by means of a map charting his record-breaking overflights, or a mosaic illustrating his feats.

Beginning in the wartime period, contemporary objects themselves (rather than their representations) also became part of monumental compositions. A Committee for Arts Affairs memo from early 1944 recommended the construction of monuments into which “authentic contemporary weaponry, which is made from eternal materials, would be inserted.” Accordingly, in the next two years, decommissioned Soviet tanks were installed as part of the Monument to the Liberation of Simferopol (1944) and the Monument to Soviet Tank Crews in Prague (1945). Pairs of T-34 tanks and ML-20 artillery pieces flanked the Soviet War Memorial in Berlin’s Tiergarten Park (1945). Indeed, the practice of integrating contemporary weaponry into monumental complexes continued throughout the remainder of the Soviet period.

In monumental sculpture, the utility of contemporary clothing as a marker of the Stalin era precluded nudity. Clothes and drapery “express the style of the [given] epoch,” argued the sculptor Sergei Merkurov. His colleague Matvei Manizer similarly rejected “timeless clothing,” and eventually, in a bout of self-criticism, denounced his older nude sculptures as lacking “historical concreteness.” Mukhina, for her part, reminisced that when the state commission approved her soon-to-be-famous Worker and Kolkhoz Woman monument, it required her to “clothe” her originally nude statues. “That will make it clear that he is a worker,” the commission’s representative allegedly explained. The same situation arose again in 1951, when a Committee for Arts Affairs council of experts ruled that Mukhina’s brigade should “work on the clothing of the figures [of the monument Young Transformers of Nature, designed for Moscow State University] [as] it is necessary to find costumes characteristic of our epoch.”

Along with figurative representations of contemporary subjects, epigraphy represented another avenue for lending an enduring, distinctive character to synthetic monuments. As a key technique of “architecture parlante,” epigraphy spearheaded the broader push for linguistic analogies in Stalinist architecture. Inscriptions on monuments supplemented the construction of commemorative plaques, which also saw a steady upsurge throughout the period. From the perspective of the problem of indistinctiveness, epigraphy allowed for specifying otherwise nondescript monuments and imparting particular content about the individuals and events that they memorialized.

As a 1950 dissertation on monuments to the Great Patriotic War (the first systematic study of these) explained: “It is evident that epitaphs and memorial inscriptions on monuments to the Patriotic War play a large and important role in . . . reporting specific information about historical events to which this or that monument is dedicated. It is difficult to overestimate the… purely historical importance of these epitaphs and inscriptions that immortalize on stone tablets the details of events and individuals’ statements.” Altogether, this logic suggested that if monuments themselves were insufficiently clear or specific, words “inscribed on stone . . . would tell posterity of the heroic struggle of the peoples of the USSR.”

Accordingly, Stalinist monuments were suffused with words. The Palace of the Soviets was to reproduce passages from the constitution and quotations from Stalin’s speeches; both eventually made it into the design of the Moscow State University Main Building. Epigraphy was perhaps most extensively employed in the composition of the Volga-Don Canal, a massive infrastructure project connecting the Caspian, Azov, and Black Seas, commissioned as a monument to the civil and Great Patriotic Wars. Nearly every canal lock, sculptural monument, triumphal arch, bust, and obelisk had a supporting inscription, whose text was approved at the highest level by a decree of the Council of Ministers.

From 1943, nearly all of Moscow’s metro stations included plaques featuring quotes from Stalin, the Constitution, and the national anthem. Metro stations’ decorative art was also helpfully labeled. A 1953 discussion of the frescoes of Kievskaia-kol’tsevaia station resolved that “there must be a text inscribed on marble . . . to make the painting understandable. As [Il’ia Repin’s] ‘Zaporozhtsy’ is understandable with its inscription; even Michelangelo’s monumental paintings have all the prophets labeled, to avoid any misidentifications.” Accordingly, inscriptions pedantically explained Kievskaia’s commemorative artwork: “M. I. Kalinin and S. K. Ordzhonikidze at the Opening of the Dnepr Hydro-Electric Station, 1932,” “The Liberation of Kiev by the Soviet Army, 1943,” “Victory Day Fireworks Display, May 9, 1945.”

Thus, synthetic art – whose provenance was further underscored through representations of contemporary props and epigraphy – became the chief means of imbuing neo-classical architecture with a distinct monumental form, thereby underscoring its Stalinist character for future viewers. Regime leaders proved receptive to this logic, endorsing synthesis as a key principle of monument composition. As such, the richness of Stalinist monuments – grand architecture suffused with sculpture and decorative art – stemmed in large part from the artistic problems of designing monuments for posterity, than from an intrinsically “totalitarian” extravagance.