The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

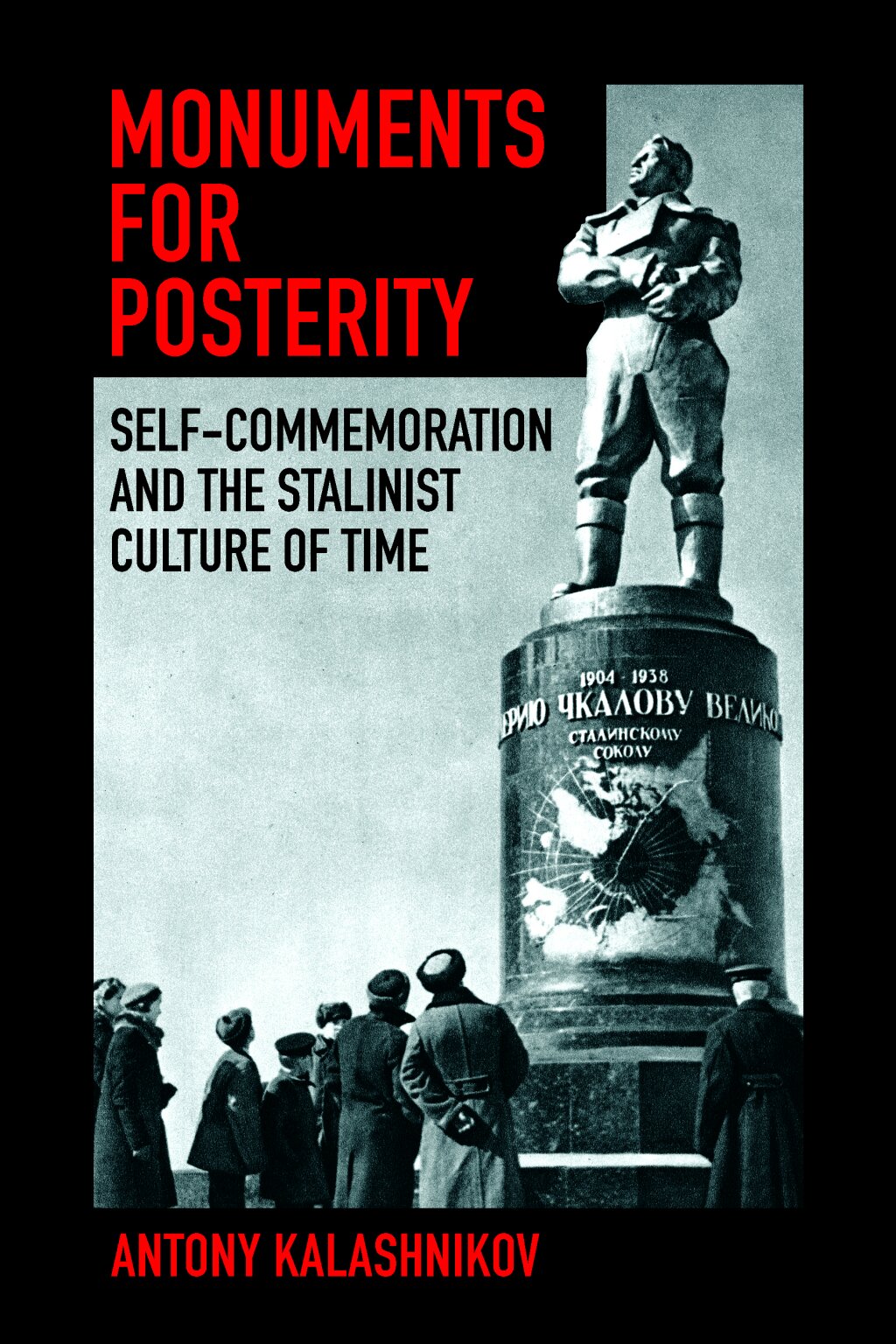

This week, the blog will be running a three-part series of excerpts from Antony Kalashnikov's new book, Monuments for Posterity: Self-Commemoration and the Stalinist Culture of Time, out in April from Cornell University Press. This is Part II; Part I can be found here, and Part III will follow on Thursday, 2/9.

Antony Kalashnikov is a postdoctoral fellow at the University of Alberta (Canada), working on Soviet cultural history.

The dominant approach to Stalinist architectural and sculptural monuments foregrounds their glorification of the ruling regime. Undoubtedly, such propagandistic considerations motivated the state’s unprecedented investment in monument building. But in order cultivate collective identification with these monuments, the regime took care to underscore their capacity to immortalize the Soviet people as a whole. Intriguingly, despite these monuments’ saturation with Stalinist political symbols and representations of “great men,” significant demographics appear to have been genuinely enthusiastic about the prospect of indirect, collective immortalization through these objects.

Among other indicators, the genuineness of public support for the Stalinist monument building program is illustrated by the sheer quantity of amateur proposals for monuments and monument designs. These expressions did not promise their authors any tangible gains beyond the feeling of participation in the process of immortalizing the memory of their era. Initially, the Stalinist regime welcomed public involvement by holding well-publicized, “open” design competitions for amateurs, alongside “closed,” professional competitions. In this way, the second, open phase of the Palace of the Soviets design competition in 1932 attracted over one hundred and fifty submissions from the public. In 1935, the youth newspaper Kolkhoznye rebiata solicited designs for the Pavlik Morozov monument, receiving over 500 from Young Pioneers. But while the practice of open competitions disappeared from the second half of the 1930s, a deluge of unsolicited proposals continued to make its way to newspapers, individual artists, architects, political leaders, and various branches of the Party and government. In fact, these often proposed monument projects that the regime was not even considering. Members of the public also interposed in closed competitions (for instance, over fifteen hundred unsolicited submissions were received during the first, closed phase of the Pantheon competition in 1954).

The sincerity of these proposals was evidenced by their occasional, unintentional political unorthodoxy or naiveté. In 1937, for instance, one letter-writer to Izvestiia suggested constructing collaboratively designed, matching monuments to Valerii Chkalov’s polar overflight, in the Soviet Union and United States. A similar, wartime monument proposal called for the erection of matching “Pillars of Friendship, Victory and Peace,” in Moscow, London, and Washington. Needless to say, Stalinist internationalism never extended quite so far.

In fact, Party and government institutions, political leaders, and art professionals were frequently overwhelmed by the volume of such proposals and suggestions, which nearly always pled that the addressee acknowledge receipt and reply with their impressions. While working on the gargantuan Lenin monument that was to top the Palace of the Soviets, the sculptor Sergei Merkurov was so exasperated by the copious correspondence from amateurs that he even complained to Politburo member and unofficial patron-in-chief of the arts Kliment Voroshilov. Nevertheless, recognizing the benefit of such collective identification with the monument building program, the regime tried to appear attentive to amateur monument proposals and to public discussion. In one case, the Committee for Arts Affairs formed a full expert review council, which met three times (!) to consider an amateur proposal for a 150-meter pyramidal Victory monument with a spiraling staircase, topped by a sculpture of Stalin holding a globe. However, because the council’s report rejected the design (noting that the structure was unstable, its architectonic composition “constructivist,” and its concept of the Stalin sculpture “naïve and conducive to unwelcome associations”), the Committee was forced to disappoint the author.

In 1944, another group of veterans petitioning Stalin to construct a commemorative theme park (provisionally named “Heroism of the Patriotic Wars”) were met with a similar response. Their fantastic ten-page proposal called for monuments, museums, memorial halls, panoramas, trophy weapons (including German steamships and submarines), movie theatres, lecture halls, shooting ranges, parachute towers, equine parks, ski hills, ice rinks, circuses, dance floors, officer clubs, beaches, amusement rides, a library, publishing house, art gallery, sanatorium, military college, stadium, airfield, “Pioneer’s Palace,” its own hydro-power station, and a 30-50 meter raised monorail. Clearly, designers of the “Heroism of the Patriotic Wars” theme park had assimilated Stalinist gigantomania and bombast, but misread the chronic lack of capacity that such rhetoric all-too-often masked. Stalin’s secretary Aleksandr Poskrebyshev forwarded the letter to Politburo candidate member and head of the army’s Political Directorate Aleksandr Shcherbakov (note the high level of involvement). Shcherbakov tersely commented that “it is necessary to explain (politely) to the letter's authors that currently and in the near future the country faces more pressing issues”; the order was promptly carried out.

The pleas that amateur proposals be acknowledged, and the efforts occasionally expended to receive a reply, testify to a strong emotional investment in the monument building program – at least on the part of some individuals. An early 1940 complaint from one amateur designer of a Chkalov monument relates his odyssey through the Kafka-esque labyrinth of Soviet bureaucracy in the quest for a reply. Having sent his proposal a year earlier to the newspaper Krasnaia zvezda, the author followed-up with the editorial office after a lengthy silence. He was informed that the project had been forwarded to the Committee for Arts Affairs. The latter, however, denied having received it. An approach to the Secretariat of the Council of People’s Commissars yielded nothing beyond a demand for the date and case number of the original submission acknowledgement from Krasnaia Zvezda. The author duly forwarded these to the Secretariat, to no avail. He therefore felt compelled to write to the Presidium of the Supreme Soviet of the USSR! An analogous story, recounted in a letter to the Deputy Chairman of the Council of Peoples’ Commissars from an amateur designer of monuments to Gor’kii and Party boss Sergo Ordzhonikidze, concluded dejectedly: “I have doubts that workers’ opinions are being considered.” At points, the regime had trouble keeping up with the enthusiasm for monument building, which it itself encouraged by sponsoring public discussions and other forms of participation. In any case, as the regime had hoped, wide sections of the public evidently felt that they were being commemorated (or, at any rate, expressed the yearning to be commemorated) in collective monuments to the era.

But even if these expressions attested to a genuine desire to be remembered by posterity, was this sentiment limited to those who had internalized the regime’s ideology and values in toto? The evidence suggests that support for the monument building program was not confined to “true believers,” but extended even to those who did not actively support the Stalinist political project. In fact, this enthusiasm – which ultimately devolved into large-scale grassroots monument building during the Great Patriotic War – overtook and even conflicted with regime priorities, ultimately prompting hostile responses.

This is best exemplified in the case of grassroots monument building in the years of the Second World War. In these extraordinary conditions, the Committee for Art Affairs’ prerogative of approving the design and construction of all stand-alone monuments was largely ignored. In fact, servicemen and civilians constructed monuments to their fallen comrades on their own initiative, on a scale and of a character sufficiently divergent from the regime’s approved archetypes to eventually provoke a hostile response. In 1950, the first systematic study of the phenomenon estimated tens to hundreds of thousands (!) of only registered graveside monuments. Incomplete military data counted at least 752 large, stand-alone monuments to the Great Patriotic War. Built spontaneously and quickly, these unsanctioned tombstones, monuments, and memorials were, for the most part, of a haphazard character: of variable artistic quality, often utilizing temporary materials available close at hand.

In early 1944, chairman of the Committee for Art Affairs Mikhail Khrapchenko approached Stalin with a proposed decree to reaffirm his organization’s authority. He complained that “local institutions, the public, and Red Army servicemen take the initiative, constructing many monuments and tombstones.” The design and construction of these, Khrapchenko alleged, “is carried out without state and artistic control and very often brings unsatisfactory results.” Although opposition to grassroots monument construction was supposedly motivated by quality considerations, it hid underlying ideological worries. For instance, the regime was uncomfortable with unsanctioned memorialization of the Holocaust (the official narrative did not recognize the specificity of Jewish victimhood); nearly all such monuments and memorial plaques were dismantled by the authorities in the postwar period. Such concerns with the ideological liabilities of spontaneous, grassroots monument construction may partially explain the officially sponsored development of standardized, prefabricated graveside monuments for individual and mass graves throughout the second half of the war and into the postwar period. These and other centrally commissioned war monuments attempted to coopt and channel popular commemoration into an officially approved mold.

Clearly, therefore, neither monument building as a practice nor the desire for perpetuating memory were limited to official culture and its “true believers.” Rather, the value of being remembered was shared, and this facilitated collective identification with Stalinist monuments, generating enthusiasm for the monument building program, even to the point of provoking the regime’s ire.