Editor's Note: This week, All the Russias will be running a series of excerpts from Susanne Fusso's new translation of Sergey Gandlevsky's novel Illegible. The volume will be out from the NIU Press imprint of Cornell University Press on 15 November and will include an introduction by Fusso, which appeared in AtR earlier this week. Part I of that introduction may be found here, and Part II here.

Susanne Fusso is the Marcus L. Taft Professor of Modern Languages and a Professor of Russian, East European, and Eurasian Studies at Wesleyan University, where she specializes in in nineteenth-century Russian prose, especially Gogol and Dostoevsky.

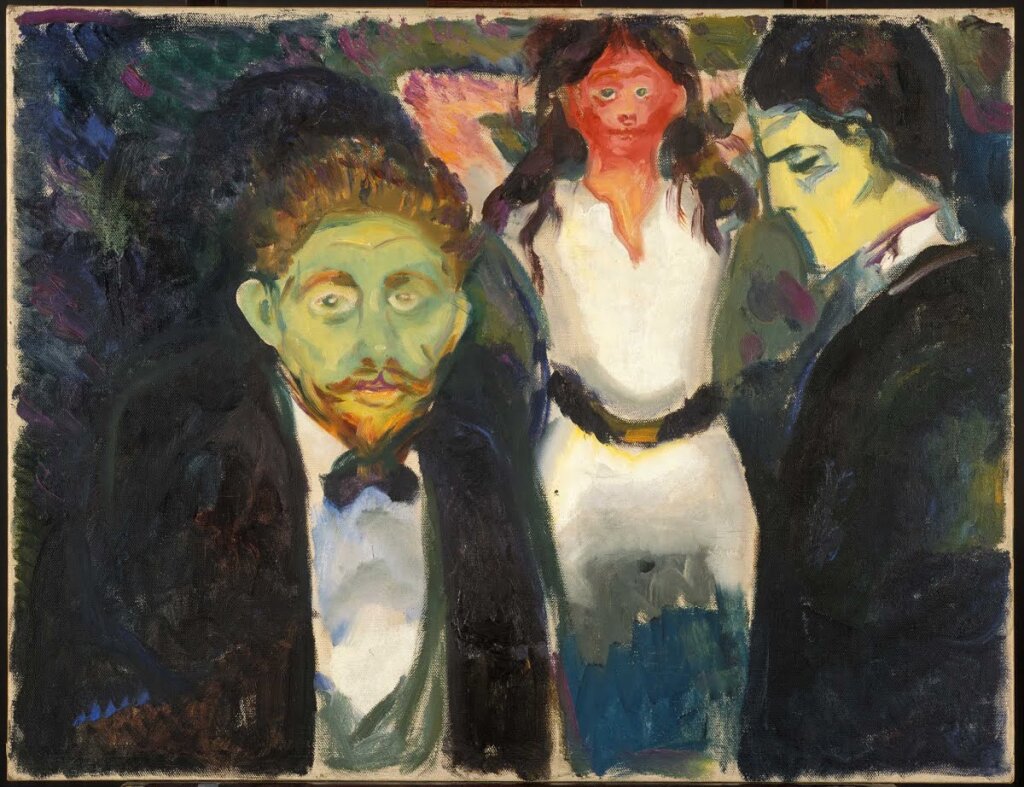

Krivorotov tried to cause a jealous scene, but Anya would have none of it.

“I have one jailer, my aunt, and that’s enough,” the young woman said to him. “If you don’t like it, I’m not keeping anyone by force.”

Krivorotov had no choice but to accept it, but his jealousy grew, came into ear and matured as impressively as that plant in the school film. From day to day he lived in a suspended state, trying to guess where the dirty trick would come from, and gloomily collecting into a pile the unbearable little things that testified to Anya’s indifference to him.

With bitterness Krivorotov noticed that the charming, unique grimace with which, as it seemed to him, Anya encountered him in particular, was not at all unique and not addressed only to him: she smiled in just the same way at Nikita; with the same captivating gesture she would straighten Shapiro’s jacket lapel; she eagerly responded to Yasen’s invitation “to drink straight from the bottle,” and at the same time with feigned reproach she would pull a long strand of hair off his sleeve. She squandered her very intimate, soul-troubling charm in a shockingly equitable manner. If Lyova, depressed by her inattention, languished and seethed on the edge of some gathering to which he himself had dragged her, it never occurred to Anya to console him and single him out of the motley group with even a fleeting glance or nod. Again and again he used to rush to the door in fury, but turning around at the threshold with the pitiful hope of meeting Anya’s worried gaze—Krivorotov dreamed of nothing more—he would see her, as before, absorbed in wine-fueled conversation, let’s hope with a person of the female sex—but usually with a downright womanizer. When Lyova would try to take revenge by starting up a drunken flirtation and getting his paws around some zaftig poetess in a too-close dance, his calculation that Anya would be jealous was not borne out: she always noticed everything, but merely winked approvingly at him across the room and continued nonchalantly participating in the general uproar. Once they were standing by the window of the studio and chatting. All at once Anya smiled from a great distance, as if through a sudden memory, to someone over Lyova’s shoulder, her smile laden with significance, it seemed to the mistrustful suitor. Krivorotov turned around: Nikita was lingering in the doorway and returning Anya’s smile, as if he had something in mind that concerned just the two of them. Usually, when Nikita caught Anna and Lev talking tête-à-tête, unlike Krivorotov he would not bother to hide his displeasure, as if he had some special rights to Anya. Krivorotov had forgotten even to think about the fact that he might really have such rights—he was too absorbed in his own suffering. The mise-en-scène in which Lev had been an uninvited witness and participant at the end of April still made him want to hit the ceiling, his inflamed imagination painting pictures of the hellish debauchery that had preceded his unexpected appearance.

He had decided to drop in on Anya unexpectedly without calling ahead, because he knew for certain that her aunt was away, and Anya had assured him that she was spending day and night writing a term paper and would be unreachable for the next few days. But Krivorotov was missing her unbearably. Anya didn’t open up right away, and when she did, Krivorotov caught the scent of wine and someone else’s interrupted merriment. Dodging his kiss as she usually did, Anya led Lev into the room, where his bosom buddy Nikita was sitting, very much at home, in the single armchair, and half-rose to greet him with a mockingly polite bow. A straw-covered liter bottle of so-called Cabernet, apparently already empty, stood on a little magazine table among textbooks and notebooks. Most horrible of all was the way Anya was dressed. She was sporting sandals and tight short-shorts (so Nikita, not Lev, was the first to see her bare legs and toes!). Her checked shirt, under which you could tell she wasn’t wearing a bra, was rakishly tied over her stomach. And so that belly button, those heels, ankles, calves, knees, and what was above them, which Krivorotov had learned by heart and made his own in imagination, in his hell of insomnia caused by abstinence and lust, had been unceremoniously ogled by a man for whom Krivorotov’s hostility was giving him a cramp in his entrails.

“I know absolutely noth - ing,” Anya said, melodramatically dropping her arms. “Absolute zero, and tomorrow is the final deadline. Nikita is dictating, I’m writing it down. So I can give you five minutes, otherwise they’ll kick me out with a bang. Want some tea?”

And she slipped past Krivorotov into the kitchen, again dousing him with the smell of wine and her frightening maidenly freedom.

“Nice,” was all Krivorotov was able to growl as he plopped into a chair.

After a minute of expressive silence he squeezed out: “Do you think this is the way a friend acts?”

“Shall I remind you how things have developed day by day?” Nikita answered with a question. “As my grandfather says in such situations, you’re complaining about stepping in your own shit.”

“Oh, come on.”

Bumping into the half-naked Anya balancing a cup of tea in her hand in the darkness of the entry hall, Krivorotov managed to open the door lock with shaking hands and stomped down the stairs.

But already a week later, after passionate vows of utter contempt and exercises in indifference, with sinking heart, like a good little boy, like one accursed, he dialed seven digits in a cherished order, just in order to hear that voice with its delectable little lisp.

He knew by heart how long the dial would gurgle as he dialed each number (the short sob of the one, after it a somewhat longer run, then a quite long trill, then two identical two-syllable beats, then the sound again gets up on tiptoe, but still doesn’t quite reach the full-fledged musical phrase that was just heard with the eight, and finally again a staccato one, bringing this unique digital strophe full circle).[i] He could make out the whining of Anya’s ring tone if a dozen telephones started cheeping in chorus, like a litter of week-old puppies in a basket.

[i]. As we learned at the end of chapter 1, Anna’s phone number is 148-22-61.

Copyright 2019 by Susanne Fusso. All rights reserved.