Everyday Soviet: Soviet Industrial Design and Nonconformist Art (1959-1989) is on view until May 17, 2020 at Rutgers University’s Zimmerli Museum in New Brunswick, New Jersey.

Farid Djamalov is a rising senior at Yale studying the History of Art.

The notorious “Kitchen debate” (1959) between Vice-President Richard Nixon and First Secretary Nikita Khrushchev sets the tone for the Zimmerli Museum exhibition Everyday Soviet: Soviet Industrial Design and Nonconformist Art (1959-1989). On a small screen in the downstairs gallery, Khrushchev boasts to Nixon: “My vas v raketakh operedili i v etoi tekhnike operedili! [We have surpassed you in rockets and in this technology!]”

The technology to which Khrushchev refers is television. The irony lies in the fact that the whole conversation was broadcasted live and in color to Americans — a recent technological feat that the Soviet Union had yet to match. During this now-legendary standoff, Nixon ostensibly advocated for a free exchange of ideas between the two countries. “You must not be afraid of ideas!” he proclaimed, to which Khrushchev retorted, “My vam govorim, vy-to ne boites’ idei! [We’re saying you're the ones who shouldn’t be afraid of ideas!]” This tense exchange, embodying Cold War sentiments of technological and ideological competition, frames the artistic and design progress in the USSR that is the subject of the Zimmerli’s exhibition.

During Khrushchev’s Thaw (1953-1964), the Space Race and American postwar culture inspired Soviet industrial designers and unofficial, nonconformist artists alike. In this exhibition, Julia Tulovsky, Curator of Russian and Soviet Nonconformist Art at the Zimmerli Art Museum, and Alexandra Sankova, Director of the Moscow Design Museum, put in dialogue 85 nonconformist artworks (from the 1950s to the 1990s) with over 300 industrial objects (from the 1950s to the 1980s) from their respective collections.

This is the first exhibition in the United States to explore Soviet industrial design from the postwar era. The exhibition is divided into five categories, clearly demarcated by distinct wall colors. The first room, painted in light turquoise, introduces the Thaw period from the late 1950s, demonstrating the international exchange and communication after the death of Stalin and the loosening of Soviet isolationist policies. The inaugural World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow (1957) allowed thousands of foreigners to visit the USSR for the first time in several decades.

Shows like the American National Exhibition, held in Moscow in 1959, exposed Soviet citizens to Abstract Expressionist art, which contrasted sharply with the Soviet Union’s only officially-sanctioned artistic style, the often rigid, propagandistic Socialist Realism. Nonconformist artists, who worked mainly in small, informal collectives under the state’s radar, found these American paintings deeply inspiring.

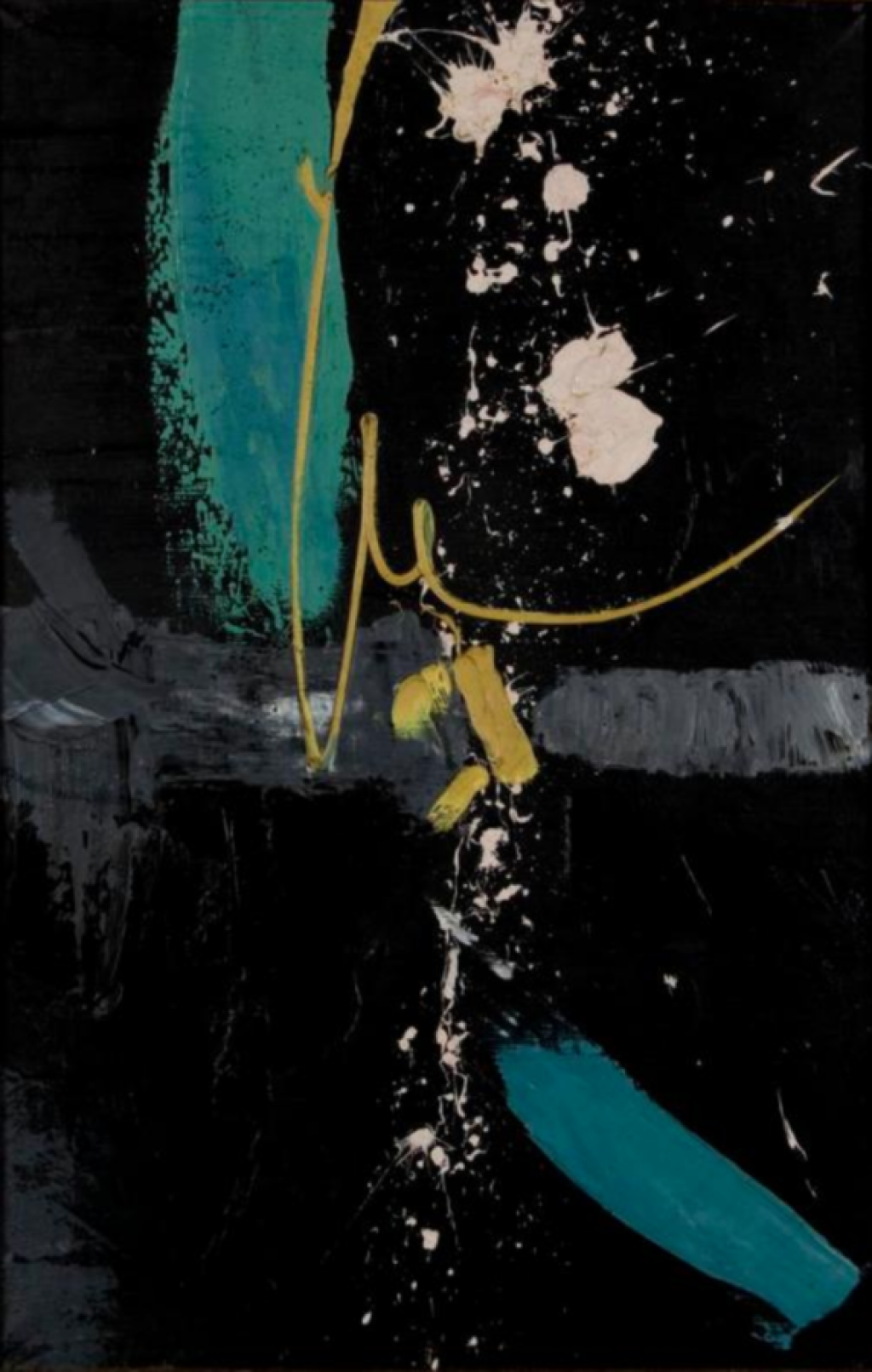

The results of this cross-pollination can be seen, for instance, in Lev Kropivnitsky’s Outer Galactic Logic (1960), which creates a cosmic collision. His Pollockian drip evoke stars, while the gestural brushstrokes à la de Kooning materialize energies over a black background.

On the other hand, Evgenii Rukhin riffs on Rauschenberg’s objet trouvé in his painting Untitled (Zipper) (1971). He places burlap pieces on a canvas and uses the facture of acrylic paint to sculpt a dimensional zipper. Rukhin innovatively appropriates in a socially conscious manner, which demonstrates the difference between Soviet and American Abstract Expressionism. He reflects on shortages of commercial goods like zippers, and the ubiquity of other commodities like burlap.

This cross-cultural dialogue extends to the printed magazines displayed in a case in the same gallery. The juxtaposition of different editions of Ogonyok and Life, the leading weekly papers in the Soviet Union and the United States, respectively, provides context. “The art of Russia...that nobody sees,” reads the title of a spread in Life from 1960, referring to a nonconformist painting hidden “in a closet in a private home in Russia.” The article glorifies the unnamed painter by highlighting their assimilated “Pollock-like abstraction.” While the artist’s identity is left out to seemingly protect them from Soviet authorities, this omission contributes to Western mythologizing of a subversive, virile, Americanized Soviet hero. This Life spread reveals the veiled political play around the positioning of these artworks and their makers: Americans were invested in shaping a narrative of the Soviet state as repressing its artists and “fearing ideas.”

The Soviet government’s relationship to artists and designers, however, was much more nuanced. During the Thaw, the state sponsored the development of innovative designs grounded in scientific research by establishing VNIITE (All-Union Scientific Research Institute of Industrial Design) in 1962. At the Zimmerli, futuristic commodities housed in a dark-blue room demonstrate Soviet interest in space exploration: a prototype for a Chaika vacuum cleaner evocative of a space rocket, woodblock printed “zvezdnaia [star]" fabric, a Photosniper FS-3 camera gun with a lens reminiscent of a telescope.

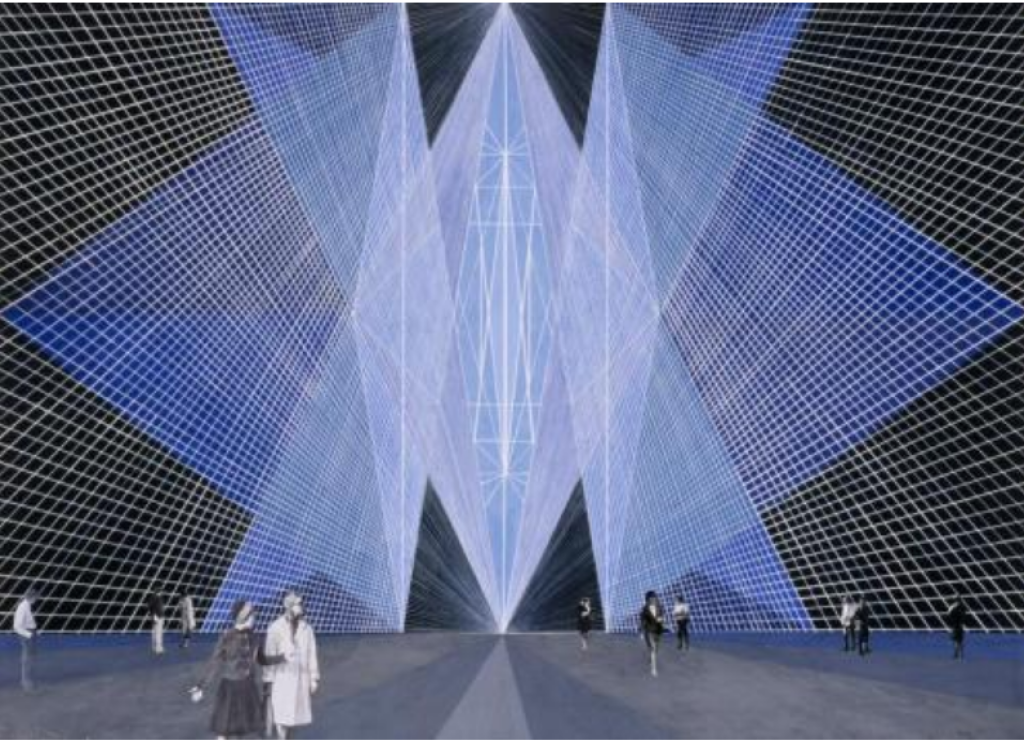

This fascination with astronomy filtered through to nonconformist artists, whose works line the walls surrounding these examples of Soviet material culture and design. In Altar for the Temple of the Spirit (1969-1970), artists Lev Nussberg and Natalia Prokurotova collaborated to create a fantastical sketch of a towering altar for a hypothetical Institute of Kinetics. The gridded planes of the sketched crystalline structure only allow the light of the luminous blue sky to penetrate through a diamond-cut oculus.

Francisco Infante-Arana reflects on questions of technology and space in his series Reconstruction of a Starry Sky (1965). He realigns stars at dusk in geometric, familiar shapes: abstracted clouds, diagonals and a singled-out star. Nussberg, Porkurotova, and Infante-Arana, all part of the 1960s kinetic art movement, demonstrate technology’s controlling relationship to nature’s divine mystery.

Taken together, these artworks and product designs communicate a shared, ambitious plan to reshape the world of Soviet citizens. The same way many artists of the Russian avant-garde, like Lyubov Popova and Aleksandr Rodchenko, designed furniture and textiles for everyday use, designers of the post-Stalin period sought to create a modern future for the average Soviet citizen.

And yet — not unlike the utopian plans of Rodchenko and his fellow Constructivists — many of these designs never got to the production stage. While the state generously funded the design phase of these projects, factories had no incentive to materialize them. As a result, and as the exhibition argues, like many of the nonconformist artists who worked underground and were unable to expose their works to broader audiences, so too did many of these futuristic industrial designs never reach the average Soviet person.

In subsequent rooms (colored grey and orange), however, the exhibition demonstrates how private and public life was shaped by what factories could, in fact, produce. Since factories created the same goods for generations, specific objects became part of the Soviet collective consciousness, laden with emotional attachments. Drab, ill-fitting work clothes and clunky (albeit sturdy) heeled shoes with little ornamentation demonstrate the reality of the Soviet people.

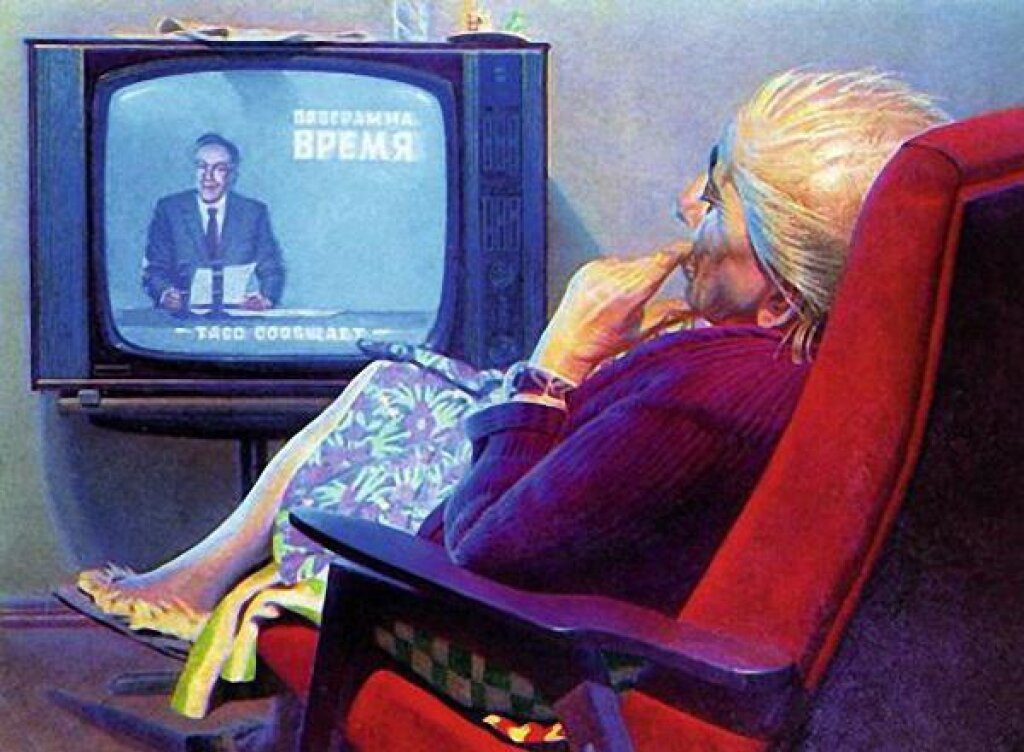

There is an element of timelessness to these clothes, since the same fashion persisted for decades. The collective memory of the stiltedness of Brezhnev’s Stagnation—especially dispiriting after the exuberance of the Thaw— is best incarnated in the recreation of a Soviet living room inspired by Erik Bulatov’s large oil painting At the TV (1982-1985). Hung on the wall of the same recreated room, this hyper-realistic painting depicts an old pensioner as she dozes off while watching the nightly news program Time. Viewers are encouraged to sit on a similar chair and watch the droning TV segment in order to experience the same sociohistorical stagnation, the the emotional impact of the barren, cookie-cutter interior.

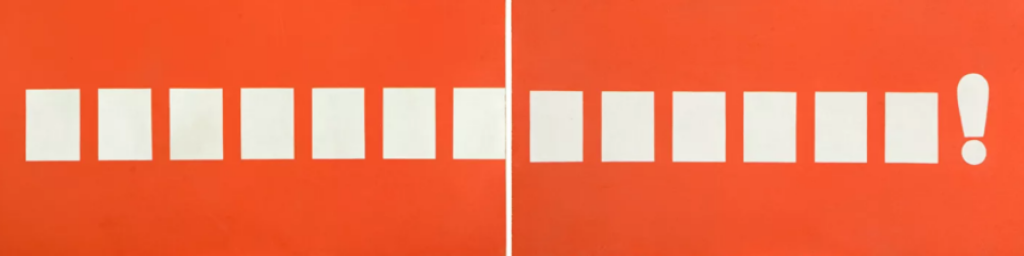

Factories also produced many iconic propaganda posters that permeated the Soviet Union. While American artists like Ed Ruscha and Andy Warhol explored the contemporaneous corporate ad culture that dominated America, Soviet nonconformists challenged the USSR’s didactic, state-sponsored posters by activating a less passive relationship with the viewers. In The Ideal Slogan (1981) artistic duo Vitaly Komar and Alexander Melamid paint a row of white boxes and an exclamation mark on a revolutionary red banner to cunningly expose the state’s aesthetics of ideological persuasion.

Likewise, in The Soviet Cosmos (1977), Erik Bulatov creates a colored drawing of Brezhnev in an agitprop style with a halo of all of the flags of the Soviet republics over his head. With the state emblem at the center of the halo, Bulatov hams up the idolatry in his Christian iconographic reference to yield absurdism.

In the yellow room dubbed “Things,” a handful of nonconformist artists appropriate material culture to reflect on the mass-produced industrial objects that defined generations of Soviet citizens. Artists like Leonid Sokov created a variety of slyly subversive interactive objects, like the enlarged reprimanding index in Threatening Finger (1974), which can be rotated like a clock hand.

In Hammer & Sickle (1997), he appropriates the Soviet emblem, but makes it a gold painted push puppet that collapses the symbol into fragments. Such objects complicate binary understandings of industrial objects and craft, since these artworks seek inspiration from industrial objects to create interesting twists that unpack the cultural significance of the state-produced objects. Sokov’s Project to Construct Glasses for Every Soviet (1975), which awaits the viewer outside of the exhibition, summarizes the show’s tensions between industry and art, official and unofficial works, and most importantly, ideas and their execution. These clunky painted wooden glasses are of a comically large size.

Project to Construct Glasses for Every Soviet" (1975) by Leonid Sokov (1941-2018)." width="258" height="260" />

They reveal the element of craft in their chiseling. The expression “rose-colored glasses” is taken literally here, with stars carved out of the thick, metonymically red wooden lenses. The hollow stars, emblematic of the Soviet Union, are the only frame through which the presumed wearer would be able to see. Tellingly, these unwieldy glasses are anything but functional. As the work's title suggests, the lenses are themselves obtrusive, their peculiar material and size making them impossible to use.

Through this piece, Sokov laconically demonstrates the complex role of innovative design and nonconformist art in the Soviet Union. While the imagination of Soviet designers percolated, many of the ideas were stymied at the design stage, never reaching large audiences. And while many of the nonconformist artists in the Zimmerli’s exhibition have achieved great fame today, the projects of these mostly anonymous industrial designers remain largely unexplored.