The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

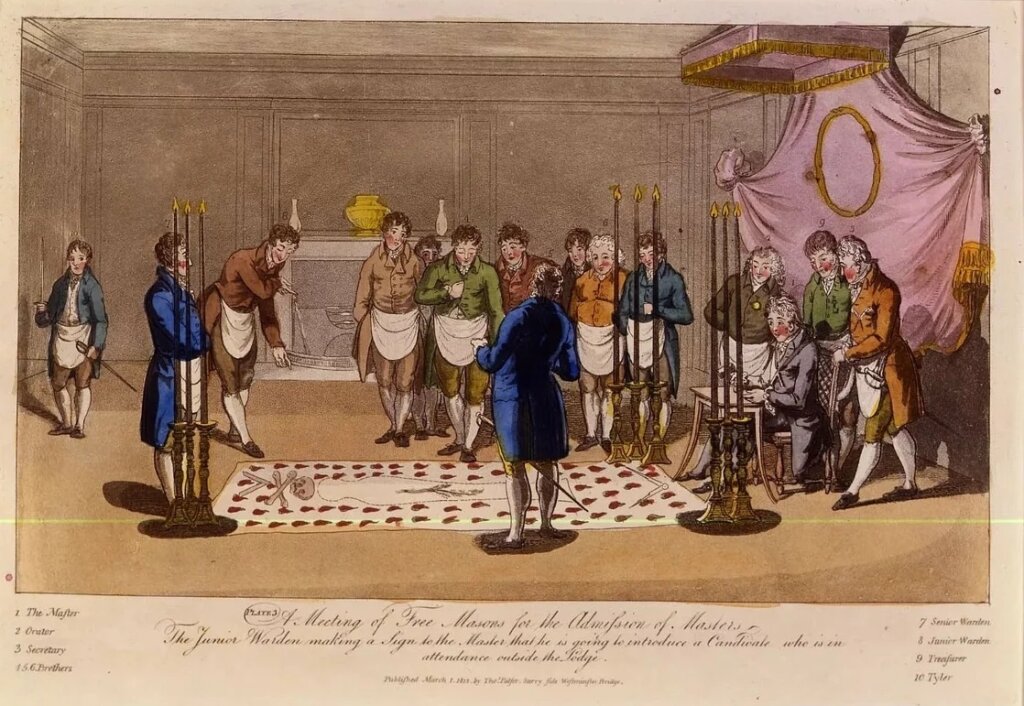

Above: “A Meeting of Freemasons for the Admission of Masters” (Thomas Palser, London, 1812). Source; Pinterest.

Yasyn Abdullaev is a Ph.D. student at the University of California, Berkeley. His research deals with conspiracy theories and state politics in nineteenth-century Russia.

The fear of the omnipotence of secret societies and the belief in their responsibility for most of the social and political upheavals in Europe formed the core of the political consciousness of Russia’s imperial elites from the late eighteenth to the mid-nineteenth century. Imported to the land of the tsars from Western Europe, the myth of conspiracy by secret societies became a pivotal official myth in the Russian Empire, shaping governmental discourse, diplomatic relations, ideology, and security policy. This mythology evolved in many peculiar and unexpected ways before undergoing a dramatic mutation by the end of the so-called Age of Revolution in Europe, which historians generally date to 1775-1848. One of the results of this transformation was an infusion of Russian conspiracy thinking with anti-Western substance, a phenomenon that remains relevant today.

The myth in question is a political narrative centering around a (pseudo-)historical plot wherein a handful of malevolent and putatively all-powerful secret societies like the Freemasons, Illuminati, Rosicrucians, or Carbonari seek either to control the world or plunge it into chaos. Although conspiracism is typical for both leftist and right-wing political traditions, the mythology of secret societies, particularly in the period of 1789-1848, belonged chiefly to the realm of conservative and reactionary thought.

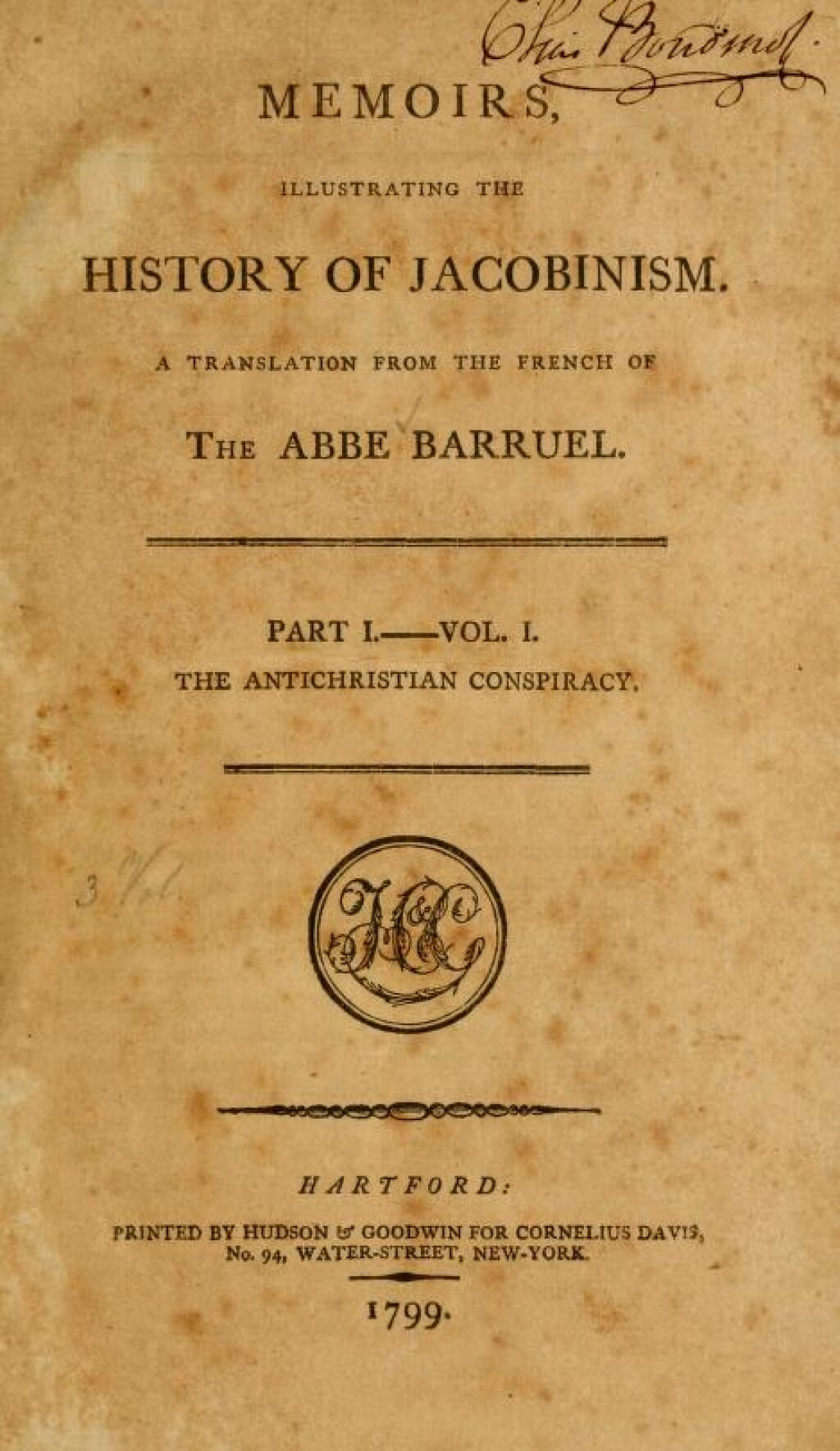

The literary tradition of conspiracy theories emerged in the writings of European secular and ecclesiastical intellectuals since at least as early as the late seventeenth century. After the French Revolution, the “big three” conspiracists—the Frenchman Augustine Barruel, the German Johann Stark, and the Scotsman John Robison—solidified the myth in their respective works. The story they laid out exposed a global plot against monarchy, Christianity, and the social order to the educated public.

The dissemination of the myth in Russia followed a similar pattern to that in Europe. Originating in the anti-Masonic rhetoric under Elizabeth and Catherine II, with an emphasis on religious and everyday prejudices, it reappeared in political discourse after 1789, that is, in the face of a potential revolutionary threat stemming from the French Revolution. The struggle against Napoleonic France and the initially reformist intentions of Alexander I helped proliferate conspiracy narratives within the country.

By the 1820s, due to the wave of revolutions in Southern Europe, the widespread mystic sentiments in St. Petersburg “high” society, and the reception of major conspiratorial essays, the myth of conspiracy by secret societies overtook the imagination and rhetoric of the ruling class. From the obsession of Emperor Alexander with the intrigues of “international Carbonarism” through his closest confidants and the empire’s most illustrious statesmen, including Karl Nesselrode or Alexander Golitsyn, conspiratorial discourse pervaded the imperial bureaucratic apparatus and still-inchoate public opinion.

The myth functioned not as a straightforward account, but rather as an intricate structure composed of multiple narratives and archetypes. One specific part of the myth that remained especially influential between 1815 and 1830, was the mythologem of the “steering committee of revolutionaries” in Paris. While it fell under the umbrella of the bigger myth, the mythologem concentrated on the image of the international center of an anti-monarchical cabal, sometimes referring to Filippo Buonarotti’s Sublimes Maîtres Parfaits.

Apart from the tsar himself, the articulators of the mythologem in Russia included notable diplomats. Thus, the dispatches of Mark Bulgari, acting Russian ambassador in Madrid in 1820, or Foreign Minister Karl Nesselrode’s reports about the 1821 Greek Revolution, serve as remarkable examples of a conspiratorial perspective on European politics. The most distinctive feature of the Paris Committee narrative was the “universal” nature of the confrontation it conveyed, with cosmopolitan revolutionaries seeking to dismantle an “Old Regime” order—presented as one uniform system—in order to replace it with another, equally uniform system, the “yoke of the tyrannical republic.”

This paradigm, which notably avoided paying meaningful attention to distinctions among nations or cultures, enabled Alexander I and the Russian governing elites to see themselves simply as a part—albeit a quite formidable one—of a brotherhood of Christian monarchies locked in everlasting struggle against the “Synagogue of Satan.”

However, not everyone accepted this way of framing the decisive battle. Deep within the most pious of Russian estates, which held a deep-seated resentment towards the central authorities for violating their ancient rights, a new form of the old myth crystallized. A group of influential Orthodox clergymen, who stood in opposition to Alexander’s church reforms, used conspiratorial language to denounce and overthrow their opponents by reinterpreting previously established narratives. This new modulation of the myth, the “mythologem of the anti-Russian conspiracy,” developed in the 1810s and '20s, and by 1830 had penetrated the tsar's court and the upper ranks of imperial bureaucracy.

This nascent mythologem told the story of a collaborative assault of various evil forces—all identified with the West—against Russian monarchy. Instead of dynastic rule throughout Europe, the key value at stake now was Russia's unique culture, its national religion and even the integrity of the state itself. Although the existential threat was still attributed to secret societies, the dominant narrative now linked these to Western European governments, especially those of France and England.

The new mythologem contained a major dilemma: on the one hand, the Russian people, due to their Orthodox morality, were supposedly immune to the conspirators' charms. On the other, most of the conspiracy narratives circulating under this motif suggested that the villains had long since penetrated Russia and assimilated to the local environment. How to resolve this contradiction? The key lay in identifying the class of revolutionaries operating within Russia as foreigners, with Poles being of particular significance.

In the 1830s, as evidenced by the annual reports of the Third Section and the correspondence between Tsar Nicholas I and Prince Ivan Paskevich, Viceroy of Congress Poland, “Polish Carbonarism” was regarded as the primary source of political instability both on the Empire's Western borderlands and in the metropole. Whether the actions of Polish “revolutionary emissaries,” who emigrated to Europe after the failed 1830 November Uprising, were real or imagined, Paskevich and others viewed them as more than just nationalists encroaching on the possessions of the colonial powerhouse in a quest to attain independence for their homeland. For the imperial administration, these Poles represented direct successors of the Freemasons and Illuminati, the “proxy” of Western cosmopolitan powers striving to eliminate Russia’s sovereignty.

By the end of the 1840s, a tectonic shift was underway in Russia's conspiratorial paradigm—from the concept of European absolutists’ solidarity in the fight with Paris as the center of secret societies, to the idea of a Russia endangered by Western actors.

However familiar it may seem from our contemporary vantage point, this process has not been “completed” at the time and does not quite equate to narratives circulating today. For instance, Nicholas I was willing to view select European states like Austria and Prussia as “anti-conspiracy” strongholds and auxiliaries to his empire. At the same time, it is undeniable that the era of Nicholas saw a crucial development in conspiratorial thinking rooted in Orthodox traditionalism. How closely Russia's anti-Western rhetoric today recapitulates these earlier conspiracy narratives is a matter for further study and debate. For now, it is clear that the history of conspiracy mythology offers many instructive parallels—and warnings.