Michael Lumbers is an M.S. Candidate in Global Affairs at New York University

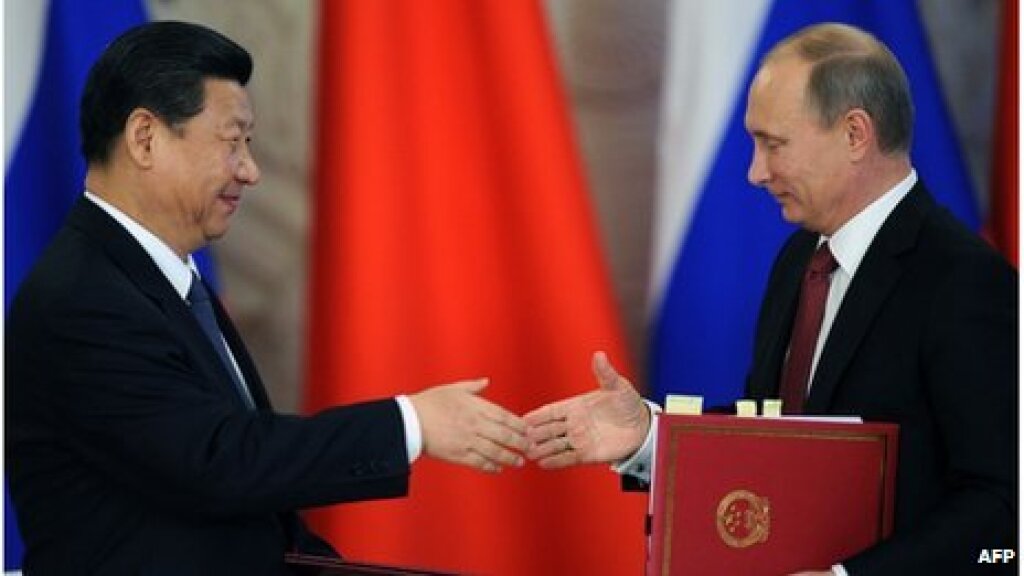

The recent decision by Xi Jinping to make Moscow his first stop on his inaugural foreign tour as China’s president caught no one by surprise. After all, the Sino-Russian “strategic partnership” has flourished during the past 20 years as a result of expanded trade, the final resolution of all border disputes and a shared interest in promoting a multipolar world order. For some alarmed Western observers, the flurry of trade initiatives announced at the March summit and familiar pledges to enhance strategic cooperation amounted to the consolidation of an anti-American geopolitical alliance. Others, seemingly forgetful that not even the bonds of ideology could prevent the violent rupture of the Sino-Soviet alliance at the height of the Cold War, have predicted nothing less than an eventual clash between the U.S. and the Beijing-Moscow pairing. Yet appearances can be deceiving. A more nuanced appraisal of Russia’s relationship with China tells us a great deal about both how Russian elites define their country’s core interests and possible trajectories for Russian foreign policy that bear little resemblance to these grim forecasts.

Aside from a long history of distrust, the primary reason why the Sino-Russian reconciliation of the post-Cold War era has fallen short of the flowery rhetoric of summit communiques is that the relationship, for both sides, remains a function of more important dealings with the United States. To be sure, mutual opposition to how Washington throws its weight around the world has created a basis for sustained cooperation between the former rivals. The elaborate stage managing of Xi’s Moscow visit can best be explained by China’s concernover the Obama administration’s recent decision toredirect America’s military, diplomatic and economic resources across the Pacific and Vladimir Putin’s reading of the Magnitsky billrecently passed by Congress as the latest example of U.S. intervention in Russian politics.

Shared antagonism can make for strange bedfellows. Yet neither Moscow nor Beijing is willing to sacrifice its own agenda with Washington for the sake of this liaison. Sharp disagreement over relations with the Americans contributed to the Sino-Soviet schism of the late 1950s. Then, Nikita Khrushchev feared Mao Zedong’s adventurism threatened to drag the USSR into a Great Power conflict that would derail détente with the U.S., a project Mao felt would come at the expense of China’s own interests. This dynamic is still alive today; Russia would be no more willing to take sides in a potential Sino-American crisis over Taiwan than the Chinese were eager to offer diplomatic support to their Russian brethren during the tense standoff with the West over the Georgian war in August 2008.

While the authoritarian Putin is commonly depicted in some circles as an American foe of the first order,this caricature overlooks his ideological flexibility. On his watch, the Kremlin has twice moved to either initiate improved relations with the U.S. or reciprocate overtures from Washington, first after the 9/11 attacks by aligning itself with the Bush administration’s “war on terror” in a bid to augment Russia’s global influence and legitimate its struggle in Chechnya, followed in early 2009 by the “reset”with the Obama administration.

A shrewd realist, Putin subscribes to Lord Palmerston’s famous dictum of having no permanent friends or enemies, only permanent interests.Those include restoring Russia’s historic Great Power status, having a seat at the table when issues of concern to are being discussed and gaining recognition of its preeminent influence along its frontiers. When closer ties to the Americans have been viewed as advancing these objectives, Putin has moved accordingly. When U.S. actions have slighted Russia –by invading Iraq without Security Council approval, driving NATO expansion or promoting democracy in post-Soviet states –he has pursued greater coordination with China as a means of asserting foreign policy autonomy and securing leverage against the much more powerful Americans.

Russia’s insistence on having its interests respected offers ample skepticism for the prospects of its relationship with China blossoming into a full-fledged alliance, and may even point toward renewed estrangement. A key determinant will be howRussia adjusts to its status as a junior partner and to pressures arising from a growing economic and military imbalance that already clearly favors China. Russian strategists are nervously watching as China’s influence steadily increases among the ex-Soviet states of Central Asia and in the sparsely populatedRussian Far East.

As China’s self-confidence grows and it focuses more of its attention on a security competition with America, its willingness to consider Russian sensitivitiescould decrease commensurately. Should this come to pass, a proud, prickly Russia would be confronted with the same dilemma it faces today with the Americansof its interests being taken for granted, but this time the culprit would be an increasingly dynamic neighbor with whom it shares a history of conflict. One of Putin’s successors may very well conclude a trip to Washington is needed to expand Russia’s foreign policy options and unnerve Beijing.