This essay was first posted on the

blog.

Venelin Ganev is Professor of Political Science and a Faculty Associate of the Havighurst Center for Russian and Post-Soviet Studies, Miami University, Ohio.

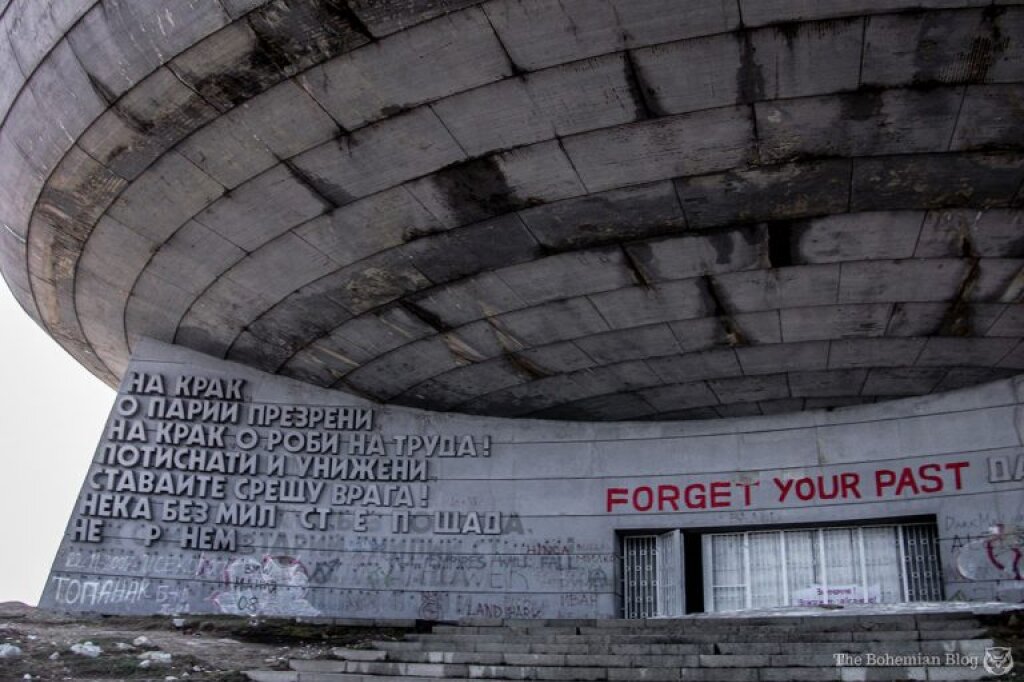

Photo: Ruined House-Monument of the Bulgarian Communist Party, Mount Buzludzha.

The publication of Kristen R. Ghodsee’s op-ed “Why Women Had Better Sex Under Socialism” in the New York Times (on August 12, 2017) created quite a stir among those of us who study communism and postcommunism, and also among reading audiences around the world. But at least so far the discussions that the text triggered have focused almost entirely on the author’s ideological rhetoric: she is a typical Cold Warrior who believes that the second half of the last century should be interpreted as a clash between two systems, communism and capitalism, and unapologetically champions one of them (the former) and denigrates the other (the latter). Much less attention has been paid to the scholarly aspects of her publication – authored by a tenured academic, it refers to evidence, comparisons of quantitative data, and analytical interpretations of historically important phenomena. How should Ghodsee’s empirical claims be evaluated?

Needless to say, the op-ed is not a scientific genre – and is usually subject to a strict word limit. But academics who make forays in mainstream journalism cannot use these trivial observations as an excuse to disregard professional standards: rigorous scholarly criteria should be invoked in order to assess the plausibility and persuasiveness of every message such academics try to convey to the general public.

In the case of Ghodsee, the message is “women under communism enjoyed more sexual pleasure.”

This contention gives rise to the following questions. On the basis of what evidence has Ghodsee’s conclusion been reached? What established facts support it, and how have these facts been gathered, systematized and analyzed? What methodological approaches to comparing “sexual pleasure” have been deployed? And why do we need to invoke “communism” and “capitalism” – as opposed to other possible explanatory factors – in order to interpret the data? Such questions are yet to be addressed in a methodical manner, and it is the purpose of this text to address them.

Sexual Pleasure Under Communism: Facts and Hearsay

The question featured in the title of Ghodsee’s op-ed article – “Why Women Had Better Sex Under Communism” – only makes sense if a logically and empirically preliminary question, “did women have better sex under communism?” had already been unequivocally answered. But has it been answered?

The first thing intellectually alert readers will notice is that Ghodsee apparently believes that comparing degrees of sexual satisfaction across populations is a fairly straightforward matter. Somewhat uncharacteristically for an anthropologist, she is willing to treat the issue as a matter of simple math: count the relevant numbers (“Eastern women had twice as many orgasms as Western women,” Ghodsee informs us), and then let the numbers speak for themselves. Some of the fans of the New York Times might find this approach problematic. Do we really possess the kind of quantitative measures and analytical matrixes that would allow us to un-problematically engage in trans-cultural, trans-generational and trans-historical comparisons of sexual experiences, and then deliver categorical judgments as to who felt “more” and “less” satisfied by such experiences? And do “the numbers” really speak for themselves? Shouldn’t statements about “sexual pleasure” be contextualized in some fashion – for example, by discussing varying cultural conventions defining gender roles, examining the different physiological characteristics of diverse populations, or probing historically evolving perceptions about the nature of intimacy? Ghodsee does not believe so: she is demonstrably unwilling to let such complicating questions muddle the seductive simplicity of her algebraic claims. Evidently, the premise on which she proceeds is that “an orgasm is an orgasm is an orgasm,” and she appears to be quite confident that a body of empirical evidence exists that lends credibility to the contention that sexual experiences under communism were much better than under capitalism or postcommunism. So let us look at the four facts mentioned in her op-ed.

First, Ghodsee informs her readers about “a comparative sociological study of East and West Germany conducted after the reunification of 1990.” I will analyze this reference in more detail below.

Second, Ghodsee quotes the opinion of Ana (sic) Durcheva, a retired woman from Bulgaria who asserts that while her own life under communism “was full of romance,” today her own daughter is sexually deprived because she is “too tired to be with her husband.” The reader is thus confronted with two statements: one about Durcheva’s own experiences, and one about what Durcheva thinks about the experiences of her daughter. Conceivably, the former statement might have some value as evidence of something. Unless validated by the daughter, however, the latter has none: it is hearsay. The only reliable source of information about the young woman’s “sexual pleasure” is the young woman herself. The op-ed makes it clear that this source has not been tapped.

Third, the op-ed mentions Daniela Gruber, a German woman from Jena with whom Ghodsee spoke in 2016. Ms. Gruber’s complaint is that she does not have the time “to get pregnant.” While this statement may shed light on the dilemmas women in one particular city in one particular region of one particular European country are facing today, it tells us absolutely nothing about the quality of Ms. Gruber’s sex life. The question whether or not someone wants to have a child has no bearing whatsoever on the very different question how much sexual pleasure they are experiencing. In fact, it is perfectly possible to imagine that a couple might have no children – and also enjoy great sex. In addition, given Ms. Gruber’s young age, it is clear that she possesses no first-hand knowledge of communism; to the conversation whether “sexual pleasures” were more abundant before or after 1989 she can contribute nothing. Ghodsee’s readers will have a very hard time figuring out why she relies on Ms. Gruber’s remarks in order to make inferences about the quality of sex under communism and capitalism.

Fourth, Ghodsee mentions her conversations with two East European professors, Katerina Liskova from Masaryk University, and Agnieszka Koscianska from Warsaw University. They informed her that before 1989 sexologists in Czechoslovakia and Poland “started doing research on female orgasm” and “stressed the importance of social and cultural contexts for sexual pleasure.” While in and of themselves these statements are interesting, they fail to allude to any evidence that would suggest that 1/ as a result of the completion of the research in question the quality of women’s sex lives actually improved; 2/ this quality was better than the quality of women’ sex lives in capitalist countries; and 3/ with the end of communism this quality began to deteriorate. It is one thing to demonstrate that a particular kind of research has been conducted – and this Ghodsee has done. It is an entirely different thing to show that the research in question transformed the real world – and this scholarly challenge Ghodsee has not addressed at all. From the fact that scholarly research addressing an important problem was launched we cannot infer that the problem in question was solved: research may be misguided, futile, ineffective, inconsequential, inconclusive – or disregarded.

To sum up the evidence Ghodsee has produced so far: her grand claim that, compared to capitalism, communism ensured greater sexual joy for women is backed up by 1/ the reminiscences of a 65-year old woman who fondly remembers the sexual experiences she had when she was in her 20s and 30s; 2/ a reference to the decision of a young German not to have a baby in 2016; and 3/ reflections on the historical record which suggests that a particular kind of research was conducted in the 1950s and the 1960s but contains no information about whether and how this research made any difference.

This evidence cannot possibly be characterized as a solid factual basis on which generalizations about sex under communism and under liberal democracy can be built.

That is why everything hinges on the first piece of empirical data Ghodsee alludes to, the above mentioned “comparative sociological study of East and West Germany conducted after the reunification of 1990.” (Parenthetically, is should be noted that this study, no matter what its findings, is an – allegedly – reliable source of information about a single case, East Germany; it tells us absolutely nothing about “orgasms” in any other communist country. Specifically, it cannot be construed as validation of the statements of Durcheva, Liskova and Koscianska). Notably, the author has provided a link to the “study,” and it might therefore be helpful to remind ourselves of what the professional conventions regarding “links” are. The function of such links is to enable the reader to easily access additional information which the author – usually because of word limit constraints – cannot discuss at length. And if the information in question is derived from scholarly research, then the professional convention is to enable the reader to access directly this research. Undoubtedly, Ghodsee is well familiar with this convention: elsewhere in her op-ed she also refers to a particular kind of research and supplies a link that takes the reader to a peer-reviewed article (authored by Ghodsee herself).

This is not the case, however, with the “comparative sociological study” link. Those who click on it will find themselves not reading a scholarly piece but watching a documentary featuring animation, East German propaganda reels, West German sex-education videos – and The Beatles speaking German. Why is it that Ghodsee has chosen to refer her readers to this video material is unclear. What is clear, however, is that as a scholarly source it is of very limited use.

In this non-scholarly documentary the main point Ghodsee makes, namely that under communism degrees of sexual pleasure were higher, is discussed, inter alia, on two separate occasions.

In the first relevant segment, Dagmar Herzog, a German-born, US-based historian announces that in the early 1990s she talked about sex to “the women in the former GDR” and that upon comparing their sexual experiences to hers, “they felt sorry for us” (notably, however, she never says that East Germany enjoyed twice as many orgasms as West Germen women). Ghodsee seems to believe that the heuristic value of this information is very high. Unquestionably, however, Herzog’s remarks leave important question unaddressed. Who were these East German women – a sample of some sort (and if so, what kind of a sample) or a bunch of randomly encountered acquaintances? Should the “conversations” Herzog mentions be considered structured interviews that make quantification possible – or just a free-flowing exchange of opinions about sex? What is the “us” that Herzog’s East German interlocutors felt pity for: Herzog and her friends? The West German female population? Western Women in general? Has Herzog’s interpretation of what this allegedly under-sexed “us” have been experiencing been validated by any other member of this group? In the absence of such information Herzog’s comments may have some autobiographical importance, but they are bereft of any scholarly significance.

The second relevant segment in the documentary revolves around the statement that after 1989 “sociologists” had “a field day” analyzing the sex lives of East and West Germans, and that what they found is that “sex in the East” started “earlier,” was “better” and happened “more often.” It is worth pointing out, however, that this statement is not made by “sociologists” explaining how exactly their “field day” unfolded: it is made by the video’s invisible narrator during a scene featuring cartoon characters (what the narrator also suggests is that East German men had larger penises than West German men – a contention to which scholarly value will be ascribed only by those who believe that the size of male genitalia is determined by the content of reigning political ideologies). In other words, Ghodsee has not referred her readers to the research of any flesh-and-blood sociologist who is featured in the documentary and who explains how the study was designed, spells out its theoretical and methodological premises, and authenticates the validity of any quantitative data that would warrant sweeping generalizations about who experienced “more” sexual pleasure and who experienced “less.”

Here, then, is how Ghodsee’s reference to “a comparative sociological study” should be interpreted: we must accept it as a proven fact that sexual life under communism was more fulfilling than under capitalism because an unspecified number of unidentified East German women told Dagmar Herzog so in the early 1990s – and also because the same opinion was confirmed by cartoon characters featured in a German documentary intended for mass entertainment.

Once again, it seems to me fairly uncontroversial to assert that no serious scholar would consider the facts adduced in the op-ed as a possible basis for any kind of generalizations.

Still, it is worth mentioning that readers who decide to watch the entertaining documentary will be exposed to information relevant to what Ghodsee has to say in her op-ed. For example, it refutes the contention that the approach to sex education in communist countries (like East Germany) and capitalist countries (like West Germany) was fundamentally different. Ghodsee repeatedly argues that whereas the former supposedly cared about the sexual enlightenment of their citizens, invested in it, and made a sustained effort to disseminate it, the latter neglected it. In fact, the difference was only a few years: sex education was launched in East Germany in the early 1960s – and in West Germany in the late 1960s. This is a minor empirical detail that merits no attention. Furthermore, those who watch the video will realize that Ghodsee’s argument that communist regimes prioritized “women’s emancipation” from the moment they were founded is untrue with regard to the most important factor contributing to this emancipation: access to abortion. Abortion on demand in East Germany did not become available until 1972 – almost a quarter of a century after the founding of the GDR (put differently, for approximately 2/3 of its duration the supposedly pro-women communist regime banned abortion).

But the most important thing those who read Ghodsee’s op-ed and then watch the documentary will learn is that the video material offers a very different explanation of the factors that actually shaped sexual behavior under communism. For Ghodsee, these factors are entirely ideological and political in nature. In her stylized narrative the quality of sex life is inextricably linked to the political fortunes of communism. According to Ghodsee, “the ideological foundation for women’s equality with men” was laid by socialists such as “August Bebel and Friedrich Engels” – a statement that reveals that the history of political ideas is definitely not her forte: apparently she has never heard of the work of classical liberals such as Mary Wallstonecraft and John Stewart Mill who published treatises on women’s equality decades before any socialist started paying attention to this issue. Once they captured power, Ghodsee’s narrative continues, communist governments immediately proceeded to implement a series of policies whose objective was women’s emancipation – and the quality of sex life improved as a result. In other words, no communism, no good sex; communism – good sex.

The only segment in the documentary featuring analysis of quantitative data casts serious doubt on the validity of this “explanation.”

The quantitative data is that in 1972 50% of East German women reported that they are experiencing no orgasms, but by the late 1980s this number had declined to 15%. The first thing to be said is that in and of itself this data does not allow any comparisons with West Germany – no evidence related to that country is discussed. But it does suggest, indeed, that more than thirty years after the establishment of a communist dictatorship in East Germany the quality of sex life in the country began to improve. Ghodsee’s problem is that, according to the makers of the documentary, this improvement was due not to the embrace of specific ideological principles, but to something far more prosaic: the superior sexual education of men. As the documentary’s invisible narrator explains, beginning with the late 1970s “the men did their homework.” In an East German context, the “homework” included listening to and reading the books of Siegfrid Schnable, the country’s most famous and accomplished sexologist. In other words, it is entirely possible that women’s sexual lives improved not because of the social policies designed to “emancipate” them or because of government-engineered efforts to enforce equality in the bedroom – it improved because men began to learn more about the sexual techniques their female partners preferred. An ideological warrior like Ghodsee would certainly yawn at the banality of this explanation. But it is empirically, analytically and commonsensically plausible. Conceivably, Ghodsee might adduce scholarly arguments that refute it. She has chosen not to do so.

To sum up: readers who are likely to be thrilled by flamboyant statements about sex, politics and ideology will certainly feel that Ghodsee’s op-ed has met their expectations. Readers who would like find a text that demonstrates how the sexual experiences of different populations might be compared in an empirically informative, methodologically sophisticated and theoretically engrossing manner will have to continue looking.

Who is Anna Durcheva? The Sexual Joys of the Top 1%

Those of us who know something about the writings of East European feminists that – unlike Ghodsee – actually lived under communist autocracy will most probably find themselves asking the same question: can the remarkably positive depiction Ghodsse offers of women’s lives under communism be reconciled with what such feminists repeatedly and movingly wrote about all the sufferings and humiliations they experienced? Is it possible to square Ghodsee’s contentions that “Eastern bloc women enjoyed many rights and privileges unknown in liberal democracies” and that “the regime met [women’s] basic needs” with, say, Slavenka Drakulić’s memorable essay “Make-Up and Other Crucial Questions” which features the following statement: “just being a woman was constant battle against the way the whole system worked”?

My answer is yes, it is possible. But in order to understand why, we have to address a different question first: who is Anna Durcheva (and not Ana, as Ghodsee misspells the person’s name)?

Ghodsee is usually described as an expert on Bulgaria – the country where I was born and raised and to which I regularly travel – and therefore it is not surprising that she invokes the views of a Bulgarian in order to substantiate her arguments. As we already saw, Durcheva laments the low quality of her daughter’s sex life. She is also the source of the most memorable quote featured in the op-ed: “The [communist People’s] Republic gave me my freedom … Democracy took some of that freedom away,” a quote that fits Ghodsee’s Cold War agenda perfectly well. So who is this person? It took me some time to find that out, but eventually I did.

The author of the op-ed does not provide any information about Durcheva’s biography, thereby creating the impression that the champion of “the Republic” is just an ordinary Bulgarian woman whose views are fairly representative. This impression is worryingly misleading. Before 1989 Anna Durcheva was a communist apparatchik working for the Women’s Committee, one of many official organizations which communist rulers considered as “transmission belt” conveying propaganda and ideological messages to “the masses” (in this case, the female masses). She was allowed to travel around the world and spent years working at the headquarters of the International Democratic Federation of Women in Berlin –which in turn means that she was paid in foreign currency and could buy anything she wished. Nomenklatura cadres such as Durcheva (characterized by Ghodsee as “communist women who occupied positions in the state apparatus”) could take advantage of the numerous privileges which Soviet-type regimes bestowed upon their most loyal servants – privileges which included much higher pay, access to special stores and hospitals, and a reserved quota for their children in prestigious high schools and universities. In other words, under a regime that tightly controlled everyone’s life chances, Durcheva enjoyed the kind of life that the elite felt entitled to. To the rest of the population the opportunity to live this kind of life was denied.

Given who Durcheva was, it is not all that surprising that she claims that she experienced a lot of sexual pleasure. She had a cushy desk job which she could take care of without too much exertions. It is very unlikely that she had to cope with the “crucial questions” Drakulić alludes to – or to spend several hours a day trying to buy food, household products, or children’s clothes. She had disposable income and disposable time – as well as the confidence and sense of self-esteem that shape the behavior of those who consider themselves to be deserving members of privileged groups. Is it so surprising, then, that she could later state that she devoted her full attention to her romances and her orgasms?

Ghodsee’s epic narrative of sexual enjoyment under communism, then, can be reconciled with East European feminists’ depressing stories of misery and deprivation in the following way: the op-ed applies to the sex lives of the top 1%; Drakulić’s observations apply to the remaining 99%. As a source of information about ordinary Bulgarian women’s sexual experiences Durcheva is as helpful as Pierre Choderlot Le Laclos’s Dangerous Liaisons would be to someone who wants to learn something about the sexual experiences of ordinary women in France in the 18th century.

In the light of the biographical information, the statement about what “the Republic” gave to Durcheva and what “democracy” took away also begins to make a lot of sense. Ghodsee, of course, treats this statement as a self-evident truth: since before 1989 there was more freedom than after, we should infer that communism is a superior system. In other words, she simply refuses to apply to Durcheva’s observation what is called “critical thinking.” What will happen if we evaluate the Bulgarian communist’s observation critically? The first thing we will notice is that it is not “freedom” conventionally defined that Durcheva has in mind: it is demonstrably true that under communism she could not dissent from the party line without suffering persecution, practice a religion without being harassed, read Solzhenitsyn without risking punishment– and neither could she participate in free and fair elections, get involved in a grass-roots effort to remove from power corrupt political elites, or file a suit against the government if she believed that her political and human rights had been violated. What exactly did the communist dictatorship give to those like Durcheva, then? High status. The regime elevated her above “the masses,” put in her hands a bit of power which she could use to lord it over others, and made her feel like a member of the ruling class.

What did democracy take away? Some welfare benefits were cut (for example, access to free child care is more restricted), but the welfare state was not dismantled: in postcommunist Bulgaria, abortion is still available upon demand; mothers are still entitled to up to three years of maternity leave; families with children still receive financial assistance from the government. But Anna Durcheva’s elite status was gone. The political system became more pluralistic and the public sphere more inclusive. As a result, former “insiders” like her became ordinary citizens – they could no longer experience the exhilarating joys that animate the lives of those who feel entitled to an insider status in an otherwise radically exclusionary political system.

In Lieu of a Conclusion

It is not that often that social scientists are given the opportunity to address the millions of people who consult on a daily basis the most widely read publications in the world. And undoubtedly many of us share the hope that if and when such opportunities become available, scholars will take advantage of them in order to demonstrate, even within the word limitations imposed in such instances, how knowledge, reason, and analytical skills might help us get a firmer grasp of complex issues. Ghodsee’s New York Times op-ed demonstrates that the opposite might also happen: her intervention into the conversation about sexual experiences under communism shows how a complex issue might be reduced to an attention-grabbing title, unwarranted generalizations, and sensationalist simplifications. In the aftermath of this intervention, would it be possible to ever conduct this conversation in a scholarly fruitful manner? That remains to be seen.

Photo Source: Source: http://www.thebohemianblog.com/2012/04/urban-exploration-communist-party-headquarters-buzludzha-bulgaria.html