This is Part III in a three-part series. Part I may be found here and Part II here.

Matthew Cotton is a PhD Candidate in the Department of History at the University of Washington, and is currently an adjunct professor in History at McPherson College.

“Where there is Stalin, there is Victory!”

On February 23, 1944, just a few weeks past the one-year anniversary of German surrender, the Stalingrad Executive Committee resolved to adopt a new General Plan for the city. This plan would present a comprehensive vision for the city’s development in the years to come, much more so than the ad-hoc restoration efforts driven by pure necessity as in the year prior. The architects who developed the general plans had high expectations for a "new and improved" Stalingrad: “According to the new adjusted general layout of the city, Stalingrad should be one of the largest industrial centers of the Union and one of the most beautiful cities in our country.”

The city owed it to those who lost their lives to rebuild and prosper. It was also not lost on the framers of this document that the city still bore the name of the man at the head of the Soviet war effort. In their concluding remarks about the general nature of the plan, the architects assert that “the planned reconstructive measures […] will turn Stalingrad into an exemplary landscape, a truly socialist city worthy of the name of the great Stalin.”

It would be impossible to discuss in detail all 97 kilometers of the plan for a new Stalingrad. For the purposes of my discussion, I will consider two illustrative cases in the emergence of Stalingrad's “hero city" mythos: the new central ensemble, which would rise out of the ruins of historic Tsaritsyn, and the mouth of the newly completed Volga-Don Canal that would form the heart of the southern Krasnoarmeisk region.

The cultural heart of the city of Stalingrad lay in its Central District, at the Square of Fallen Fighters. The square is located a few hundred yards up the bank from the Volga, situated near the city’s main rail station and one of its most historic cathedrals, and is easily accessible via the city’s main north/south thoroughfare (once Prospekt Stalina, now Prospekt Lenina) and the city’s tram lines. Before the battle, this pedestrian square housed a memorial to the 55 communist defenders executed and buried on this very spot when the city was taken by Wrangel’s White Army forces in 1919.

“The Square of Fallen Fighters” (Ploshchad’ pavshikh bortsov) had long served as the city’s parade grounds, a backdrop for addresses by local officials and visiting dignitaries, and the nucleus of holiday celebrations. The square, once ringed by the red-brick buildings of old Tsaritsyn as well as modern Soviet constructions, such as the widely celebrated Univermag department store, would be left a wasteland when Paulus himself finally surrendered there on February 2, 1943.

What to do with this space after the battle, however, was a point of great contention. Eager architects sought to immortalize the Red Army's monumental victory in stone. Early proposals included a sky-scraping Palace of Labor that would dominate the city’s skyline and serve as the center point of the city’s transportation networks. However, these grandiose proposals received harsh criticism from local administrators and planners dealing with the reality on the ground—not only would such lavish constructions take years to complete and suck up valuable resources and laborers, they would radically alter the historic character of the city.

Instead, it was finally decided that a new park, the Alley of Heroes, would connect the Square to the Volga’s embankment, a narrow sliver of land where the city’s defenders never yielded to the German onslaught to the river. This embankment itself would be transformed, with marble steps running down all the way into the water, with tiers for statues, fountains, walking paths, and eventually one of the city’s premier theaters. These three connected parks—the Square of Fallen Fighters, the Alley of Heroes, and the 62nd Army Embankment, mark the cultural and spiritual heart of Stalingrad and Volgograd today.

Hardly any of the structures that stood before the war, be they in the style of old Tsarytsin or the additions of socialist Stalingrad in the 1930s, could be salvaged. Ultimately, designers decided that the newer Stalinist aesthetics—sweeping façades of marble and granite, complete with neoclassical arches and columns, as well as (of course) the iconic “layer cake” design—would predominate. One of the most prominent structures to adopt this look was the train station, which served as the gateway to the city for visitors entering by rail. Its layered design, complete with a clocktower spire standing 67 meters above the square below, was clearly inspired by the Seven Sisters in Moscow.

Vokzal

is one of the Central District’s most iconic structures. For decades, its clocktower was the highest point in Stalingrad’s skyline. Source: Photo taken by author in Volgograd, Summer 2018In addition to showcasing the pinnacle of Soviet architectural style and creating a well-ordered parade grounds reminiscent of Roman antiquity, the ensemble's open format left plenty of space for war monuments. The Obelisk that stands at the entrance to the Square of Fallen Fighters, while the Eternal Flame that sits before it is a simple yet powerful memorial to defenders of not one, but now two of the Revolution’s most important struggles.

The combined effect of the uniform façades, with their historic significance, makes the Central district—called the Stalin District from the end of the war until 1961—feel like a living museum, a space where memorialization and daily life are inexorably merged. This composition formed the beating heart of the “hero city.”

The district of Krasnoarmeisk, the southernmost of all the city’s suburbs, was little more than a collection of villages before the war began. After the battle, however, its importance for the city and its residents grew. Facing scarce resources and labor power, Stalingrad’s planners briefly debated excising the district to form its own city. This idea was resoundingly rejected by the district itself—Krasnoarmeisk would remain bound to Stalingrad, with all the prestige that being part of the “hero-city” entailed.

The destruction of the city’s old commercial river port was so thorough, and the river there so choked with debris hidden under the surface, that planners decided to relocate it to the south. Their decision followed calls from the Party center to renew efforts to connect the Volga and Don rivers with an overland canal, which would theoretically connect two of Europe’s greatest river systems and allow watercraft to travel between the Black and Caspian Seas. While the shipping economy (as well as a large chemical plant) would make up the core of the district’s long-term economic livelihood, it was the Canal that would shape the character and composition of Krasnoarmeisk.

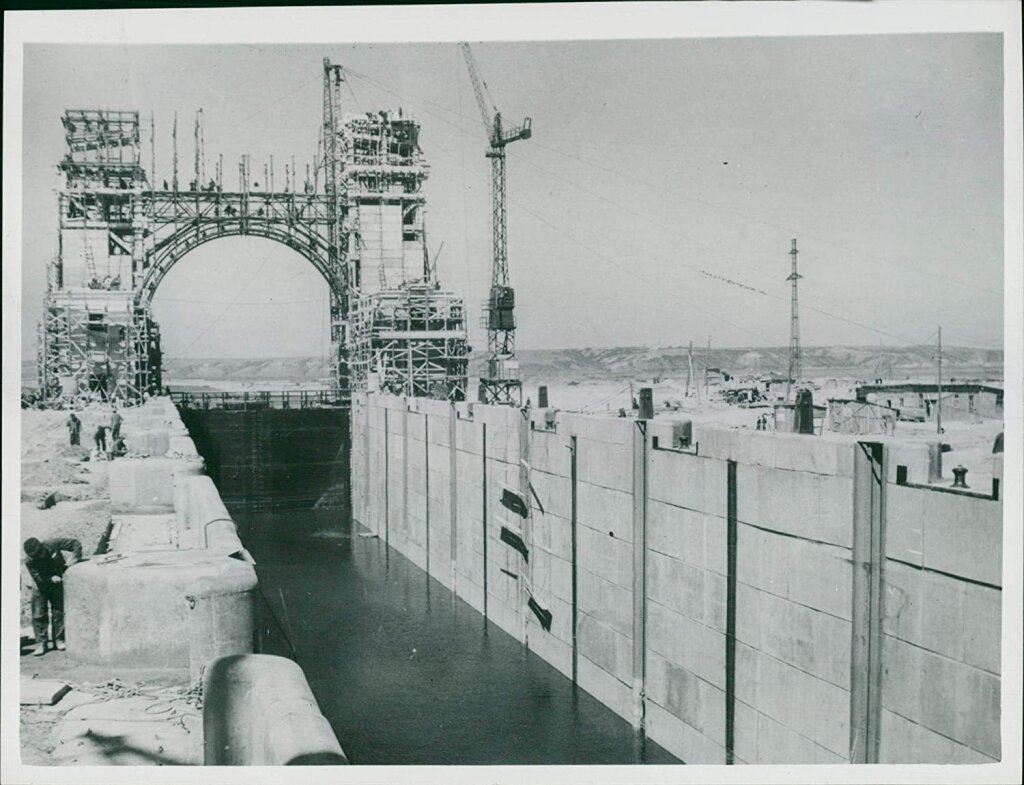

The Canal was itself a monumental feat. Nearly 101 kilometers lay between the nearest points of the two rivers. Even amid all the other reconstruction efforts in the city, the building of the Volga-Don Canal would dominate Stalingrad's image and prestige for years to come. The canal had all the hallmarks of a great Stalinist construction: driven by a single-minded objective, it was literally earth-shaking in scope and promised to redefine the possible for future generations.

Because the canal would empty into the Volga in Krasnoarmeisk, the district was set to benefit greatly from the influx of resources and labor (including thousands of POWs fresh from the front). The Canal would also come to comprise the district’s core composition, as bridges, parks, statues, and decorative architecture dedicated to it would become the defining features of the neighborhood, giving Krasnoarmeisk its own set of cultural landmarks to finally rival those of its northern counterparts.

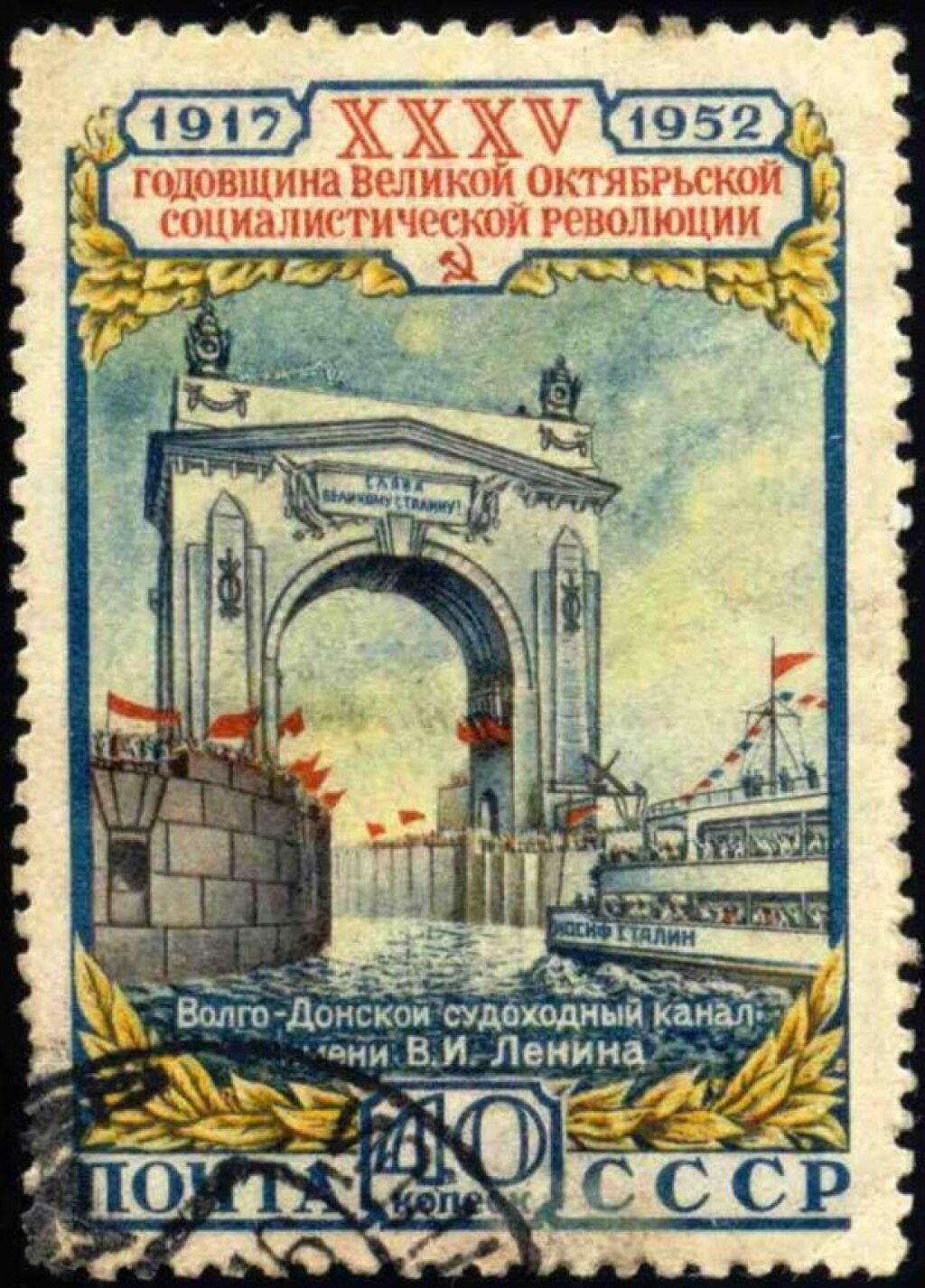

The ensemble's final shape was yet to be determined, however. Triumphal arches, sweeping façades, and columns of stone were proposed not just for the locks at the far ends of the canal, but for each of the nine locks in between. The ultimate design was a massive arch spanning the canal, with parks flanking it on both sides. While the arch would become one of Krasnoarmeisk's most recognizable features, every one of the Canal’s thirteen locks had a similarly grandiose design — even those situated in the middle of empty steppe.

Finally, on a promontory overlooking the point where the canal enters the Volga, the renowned sculptor Yevgeny Vuchetich was commissioned to create a 26-meter-tall statue of Stalin himself, set atop a massive stone pedestal. This final statue of Stalin, which for a time was the largest of any such monument to the Soviet leader in the entire Soviet Union, was taken down and replaced with a similarly monumental statue of Lenin in 1961 as part of de-Stalinization. Even after this event, however, Vuchetich would remain engaged with Stalingrad myth-making, becoming the project manager of the massive memorial complex that would come to stand at Mamayev Kurgan.

When construction was finally completed in 1952, its inauguration would come to be a memorable day in the city’s legacy. While Stalin had been invited to witness the opening ceremonies, the leader ultimately remained in Moscow. In his stead, a new riverboat, christened with the name of Stalin, passed under the triumphal arch that spanned the Canal after its final lock.

The editors of Stalingradskia pravda noted the advent of a motto celebrating the Canal’s opening and encapsulating the city's pride: “Where there is Stalin, there is Victory!” The implication is clear. For a city bearing Stalin’s name, anything less than the remarkable recovery of Stalingrad as a thriving metropolis from the point of near destruction in under a decade was unimaginable.

Yet the city, like the rest of the Soviet Union, would soon face the inevitable question lurking behind this slogan: “What will happen when Stalin is gone?” Stalinism, I argue, had been built into the city’s foundations. Despite the campaign to rename the city from Stalingrad to Volgograd, and the attendant scrubbing of the leader’s image and name from public space, Stalinist culture was already ingrained in the city’s built environment.

Khrushchev and his successors would attempt to reclaim the central meta-myth of the city from Stalin and reattribute it to broader themes of Soviet sacrifice and victory in the Great Patriotic War. However, even this narrative—for better or worse—was irrevocably linked to Stalin, who had overseen the war effort and whose bloody revolution in the 1930s had ultimately given the country the tools to prevail over the fascist invasion. That link has proven a lasting one, lasting beyond Soviet collapse. Today, Volgograd continues to contest Stalin’s legacy in a series of debates unlikely to be settled anytime soon.