The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

This is Part II of a three-part series on the edited volume Socrates in Russia, edited by Alyssa DeBlasio and Victoria Juharyan. Part I may be found here and Part II here.

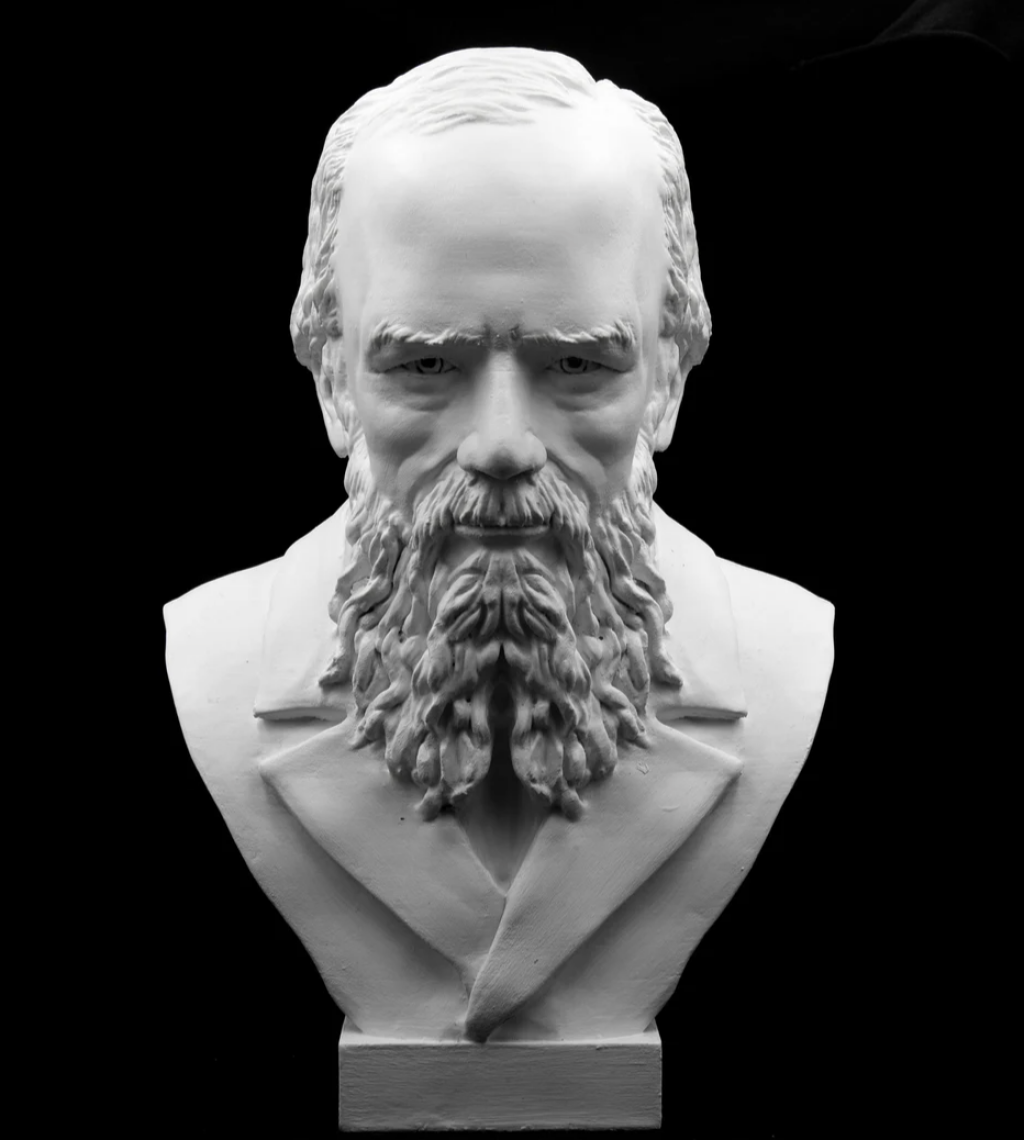

Through the end of 2022, Brill has made some chapters from Socrates in Russia available in Free Access. Brian Armstrong’s chapter, “Writing the Russian Socrates: Dostoevsky, Skovoroda, and the World of The Brothers Karamazov,” is available in here.

Brian Armstrong is Associate Professor of Philosophy at Augusta University and author of “A Philosophical Approach to Teaching Crime and Punishment” in the MLA’s Approaches to Teaching Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment (eds. Michael Katz and Alexander Burry, 2022).

Part III: Writing the Russian Socrates: Dostoevsky, Skovoroda, and the World of The Brothers Karamazov

What is the role of reason in Dostoevsky’s fiction? Dostoevsky is often charged with irrationalism, yet, generally speaking, irrationalism is a matter not of the rejection of reason but rather of the rejection of a certain conception of reason. There is also a meaningful distinction enacted in his novels between the reasoning of positive (beautiful) characters and those who are spiteful and neprivlekatel’nye. The former fare better when they reason well, as Myshkin (generally) does not and as Zosima reliably does.

I would thus argue that for Dostoevsky, the use—and reputation—of reason is an issue of central concern, as is the attempt to delineate its many uses and abuses. The Greeks of Classical Athens had many words for what we would loosely call “thinking” and those who think. We’re well aware of philosopher (φιλόσοφος “philosophos”) and sophist (σοφιστής “sophistês”). But there were other terms, such as phrontist (φροντιστής “phrontistês”), which was a slang term (according to A. E. Taylor) that literally meant to be anxious or worried about something but which came to be used (by Aristophanes, most famously) to describe Socrates.

By that time, the term phrontist was used to describe someone who thinks up thoughts—in the sense of concocting something fantastic that leads us away from the truth (even if it seems to do the opposite). And this phrontist, together with his followers, constituted a phrontistêrion—a “thinkery” or “thought factory” (as translated by Inhee Berg). There, the phrontist “hatches ideas […] that make the worse reason appear to be the better in his pretense of knowledge” (Berg again). He tinkers with thoughts in order to create what he needs. He’s a thinkerer, to coin a Seussian-sounding word.

These “thinkerers” are found throughout Dostoevsky’s fiction (think of Pyotr Verkhovensky or Smerdyakov), and some of the key dangers they pose are the same as they were back in Classical Athens. In particular, these “thought makers” pollute their epistemic environment insofar as they encourage misology throughout society: some come to hate reason because of what they see these “phronists” do with it, while the phronists themselves, in abusing reason, also display a hatred of it.

This in turn leads to epistemic chaos, insofar as people no longer know how (if they ever did) to rationally reflect on their beliefs. Amidst such chaos, we come to believe simultaneously that no one can claim to know what is true and that we ourselves (alone) can claim to know what is true. We don’t know whom to believe, and yet, given that we must believe something and in someone, our belief formation is guided by highly questionable (and unquestioned) standards, and the someone in whom we each believe might as well be our own self (whatever a “self” is). (Here, Raskolnikov’s trichinae dream comes to mind.)

In “Writing the Russian Socrates: Dostoevsky, Skovoroda, and the World of The Brothers Karamazov,” I turn to the work of the eighteenth-century Ukrainian philosopher Hryhoriy Skovoroda in an attempt to close the gap between two exemplars of epistemic virtue in the face of epistemic chaos: Socrates and the central Socratic figure of Dostoevsky’s fiction (Zosima). In particular, I draw on Skovoroda’s metaphysics and epistemology to articulate a conception of Zosima as a Russian Socrates.

Central to my argument is Skovoroda’s belief that the proper development of reason is necessary in order to cheer the spirit, calm the mind, and render the heart seemly. This requires that we aim not simply to each know our own self but also to know ourselves, with the implication that the self is not a solitary thing. This in turn requires that we move from seeing others as mere corporeal bolvany (animated blockheads, as it were), whom we know through the many shadows they cast, and towards seeing them each as a tvar’ (creature), which is also a word that carries a special charge in The Brothers Karamazov.

Seeing the other as a tvar’, in the proper sense of the word, enables us to avoid the damaging either/or of free will and determinism: to treat people as always and in all ways free is to hold them up for constant condemnation, yet to treat them as always and in all ways determined is to treat them as objects (not persons). The challenge is to treat people as always potentially free and yet as if they could not help themselves. The latter challenge helps us to avoid crippling condemnation (as we might mistake a shadow for the other person); the former challenge points us to who the other actually is with an eye toward who they might become.

This argument, however, started in a very different place. At first, I aimed to focus on salient points of similarity (whether between Socrates and characters in Dostoevsky’s novels or between Plato’s genre and themes and those of Dostoevsky), but I gradually turned to a very different question: “How would being in Russia—or being Russian—change Socrates?” In other words, Socrates, in order to be a Socrates in a different culture, would not look and act just like the Socrates of classical Athens.

Take, for instance, Porfiry, the pristav of investigative affairs in Crime and Punishment. Vadim Golstein has written an excellent article on the similarities of Porfiry and Socrates. However, there are also significant differences. If we think of Porfiry as an early attempt by Dostoevsky at what Skovoroda would call “a Russian Socrates,” we can work to articulate what the “original” Socrates would lack (or need) in Russia, and how Porfiry might provide what is needed. In other words, Porfiry both looks and does not look like Socrates because he was created by Dostoevsky to speak to the Socrates that Russia needs (although Dostoevsky, of course, would never put it that way). We can also treat Dostoevsky as testing new versions of this Russian Socrates with the characters who engage wrongdoers with an eye toward their redemption: Myshkin (with Rogozhin), Tikhon (with Stavrogin), Makar (with Versilov)—and, of course, Zosima and the Karamazovs.

In the chapter, I focus on the early dialogues between Zosima and Madame Khokhlakov, who I treat as a Polemarchus of sorts. It’s a dress rehearsal—one of many in Book II—for key dialogues in the novel in which reason plays a crucial role.

Socrates—and Plato—would of course deny that he (Socrates) is a phronist—a thinkerer. He is a Socrates who thinks up thoughts to make our thoughts better, not worse. But the distinction between the one who aids and the one who corrupts is easy to miss or mistake, especially if a society has no Socrates at all. To call for a Socrates, as Skovoroda does, is to assert that contemporary society lacks even the possibility of making the distinction properly.

Skovoroda, in particular, is not calling for a particular way of life, but rather for the possibility of a philosophy for it. What’s needed, then, is one who can show that some kind of thinking is needed—but not just any kind. It’s a kind of thinking that can help one tarry with the truth in the midst of chaos. It’s a matter, for Skovoroda, of human nature: reason is an essential part of what it is to be human, and to let that atrophy (through the demonization of reason and, by extension, others) is, in essence, to provide entry to demons.