We at the Jordan Center stand with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

Joe Colleyshaw is a PhD candidate in the Slavic Studies Department at Brown University. His work focuses on contemporary cultural memory in Russia and the rehabilitation of late Imperial Russia in Russia today.

For any Westerner visiting Russia—at least, until recently—the usual first expedition would be to Moscow and St. Petersburg. Tourists tend to follow a well-established itinerary of museums, churches, and palaces considered central to Russian history. Russians, too, actively engage with these physical manifestations of bygone eras.

The juxtaposition of imperial with Soviet with post-Soviet structures raises the question of how today's Russia relates to its own past, a central consideration within my own doctoral work. The 2015 construction of a permanent pavilion at Moscow’s VDNKh park created a key resource that helps answer this question. The "Russia: My History" pavilion is part of a wider trend within the Russian Ministry of Education, which has for years sought to create a standardized interpretation of the past. Indeed, similar pavilions have appeared across major Russian cities throughout the past few years.

The parks were conceived as an educational tool on Russia's past for teachers, students, and the broader population. Exemplifying the Russian government's statist view of the past, these sites have rightly become the subject of intense academic study. Among the exhibits, it is the one dedicated to the Romanovs that has informed my own work because of its focus on key moments in Russian history during the Romanovs' leadership.

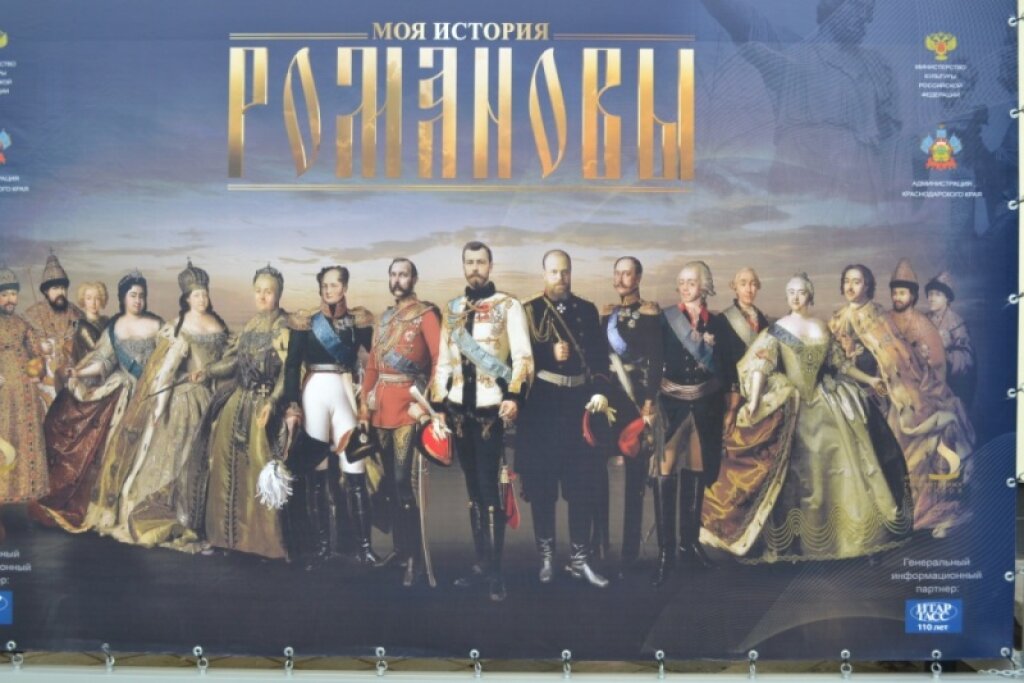

Approaching the structure, visitors find a huge "Russia: My History" stand carved from planks of wood, painted in the red, white, and blue of the Russian flag. Designed to enable a quick selfie, this display is also part of the parks' didactic purpose. Along the glass façade are portraits and slogans of various historical figures, including an image of Tsar Alexander III alongside the slogan "Russia only has two allies: her army and her fleet." This bit of saber-rattling immediately makes clear that Russia's past is best understood as both glorious and militaristic.

The Romanovs exhibit includes over 10 multimedia rooms, with each tsar accorded their own room containing interactive boards and projections detailing their achievements and the developments that occurred during their reign. The information is presented in simple and engaging form, providing a plethora of "fun facts" and easily digested narratives to guests of all ages. The exhibit raises a question applicable to many contemporary public exhibition spaces: are History parks rightly considered museums, multimedia centers, or hybrids of the two? "Russia: My History" includes no historical artifacts; instead, the visitor must glean the facts themselves, along with any interpretations, from information boards alone. This format leaves far less room for "misinterpretation" (as defined by curators), promoting the exhibit's didactic goals.

Three core themes define the exhibit, the first being empire. In each room of the exhibit, the first infographic that meets the eye is large map of the Russian empire marked with the years of the corresponding tsar's reign. While the displays themselves are static, comparing successive maps reveals how the empire's borders shifted across the Eurasian continent from Warsaw to Vladivostok and into Finland, Central Asia, and the Caucasus. Each tsar's acquisitions are indicated in a bold green, while lands "lost" are marked in red; other infographics include bars denoting increases in population and the establishment of towns and cities. These simple graphical representations tell a clear story of "progress" toward maximal territorial holdings while eliding the human, political, or social costs involved in the Russian Empire's expansion. Nor do these maps discuss the implications of incorporation into "greater Russia" for non-Russian ethnic groups or adherents of religions other than Orthodoxy.

A second theme of the exhibit is the standard by which Russia's historical leadership should be judged. The centrality of autocracy is hard to miss: the visitor is given to understand that conquest, glory, and the promotion of Russia’s interests at home and abroad are the parameters that define each tsar's success. Through careful use of the space along with specific imagery and color palettes, the exhibit subtly directs the viewer toward certain tsars and away from others, effectively placing them into a specific hierarchy. Rather than emphasizing more "liberal" Russian monarchs like Catherine II or Alexander I, the exhibit gives the more repressive Nicholas I and Alexander III pride of place. In the cases of more conservative monarchs, the exhibit takes great care to portray them as patriotic rulers who placed the development of Russia at the heart of their political programs—including through economic and technological means like the building of Russia’s railway or enacting protectionist policies for Russian grain.

Female rulers are easily overlooked in the exhibition space. Housed in notably smaller rooms and described in more modest terms, the Romanov tsaritsas are positioned as ineligible for the laurels accorded to their male counterparts. Their information slides and imagery abound with stories of their lovers, favorites, and ministers—all men—acting on their behalf and inserting themselves into the politics of the day. Since the male tsars' narratives do not contain this element of "help" from women, viewers are led to conclude that the leader Russia most needs must be not only strong, but male.

The exhibit's final narrative relates to the evergreen question of how Russia's imperial past affects its present. As the last ruling representative of the Romanov dynasty, Nicholas II is called upon to begin to speak to this issue. In contrast to the rooms dedicated to his predecessors, Nicholas’ room features a photograph of the tsar with his son. The choice to represent Nicholas II with an intimate family photo, rather than an official portrait, seems designed to evoke sentiments of regret for a bygone era and mourning for his personal tragedy. Meanwhile, the exhibit's depictions of the First World War and February and October Revolutions actively exculpate Nicholas. In the curators' version, both sets of events were caused by internal divisions and foreign plots devised to bring about Russia's downfall. Though the exhibit does not entirely ignore the negative aspects of Nicholas II’s rule, it tempers any possible critical gaze and offers an airbrushed version of Imperial Russia's last tsar.

"Russia My History" and other, similar history parks are a remarkable testament to the state of historical memory in Russia today. These expensive and intricately crafted productions make clear the importance of the imperial narrative to the "soft power" component of Russia's statecraft. The Romanovs exhibit in particular accords with the stilted view of the past that Russia’s political center has been crafting for decades. As the war in Ukraine demonstrates, these types of geopolitical narratives are anything but harmless.