The Jordan Center stands with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

This post features the History Grand Prize winner in the Jordan Center Blog's third annual Graduate Student Essay Competition.

Luke Jeske is a PhD candidate at UNC-Chapel Hill. His dissertation is tentatively entitled "Orthodox, Pilgrimage, and the Forging of Russian Identities, 1774-1914."

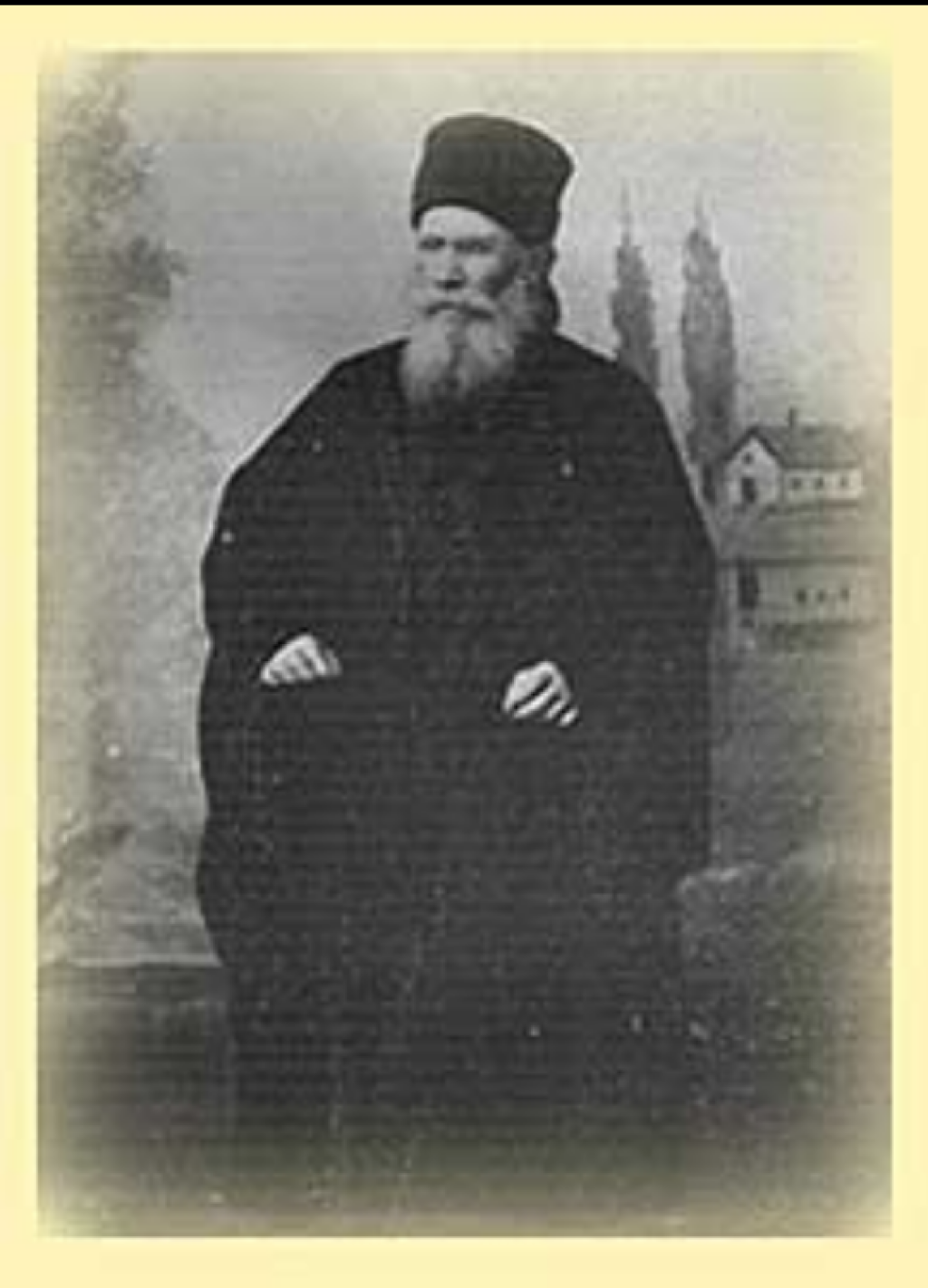

Above: Schemamonk Ilarion, author of the book that began the imiaslavie movement. Source

As the world evolved rapidly in the early twentieth century, Russian Orthodox Christians were actively engaged in negotiating numerous boundaries within and around their faith. They contested the blurry dividing lines of various dichotomies: secular/religious, heterodoxy/orthodoxy, populism/patriarchy, finding new ways to engage in the key debates of their day. Reading audiences devoured anything in print. Clerics structured their ministries to meet parishioners’ changing needs and realities. Peasants went on pilgrimages and dutifully donated their spare kopeks to their chosen institutions. In general, the Russian Orthodox faithful tended to pursue their spirituality in a collaborative and civil manner.

In some cases, however, disputes swelled into dramatic controversies, leading to the explosive convulsions we associate with the end of empire. This essay examines one such event, the so-called “imiaslavie” or “Name-Glorifiers” controversy that unspooled across Russia and Mount Athos—the name of both a mountain jutting out of the Aegean Sea, and its peninsula, which houses the epicenter of Orthodox monasticism. Besides temporally coinciding with the end of the Russian Empire, the imiaslavie dispute intersected with broader questions germane to the dissolution of the tsarist regime, issues of mass religious and political engagement and evolving centers of cultural power.

The imiaslavie controversy emerged from ambiguities in Church teachings and believers’ growing desire to pursue piety and personal salvation. In 1907, Schemamonk Ilarion (Domrachev) published his autobiography, Na gorakh Kavkaza, which implied a connection between God’s name(s) and His essence. Domrachev and his supporters grounded their theory in an array of relevant sources, including the Old and New Testaments (e.g., the Hebrew Bible’s Tetragrammaton, Philippians 2:9, etc.), the Orthodox Catechism (where the Name of God is “Holy in and of itself”), and works of influential Church Fathers, especially Gregory Palamas. This interpretation enjoyed widespread popularity because it dramatically reduced the distance between believers and their God by encapsulating Him and His energies in a single name that could be spoken, prayed to, and thought. But, if incorrect, Domrachev’s formulation constituted a highly heretical teaching that oversimplified and limited a boundless and omnipotent God.

By 1912, the movement had spread to Russian-dominated parts of Mount Athos, namely Panteleimon Monastery and the smaller Andreevskii and Il’inskii dependencies or skits. For the greater part of a century, thousands of Russian subjects flocked to these sites in order to experience asceticism and perform their piety for the Almighty. Predisposed to seek spiritual enlightenment, many Russian Athonite monks found themselves drawn to imiaslavie for its practical implications. If “Jesus,” as one of God’s names, contained His essence, then one could draw closer to the Lord by repeating, praying, and meditating on that name. The contemplative solitude of the monastic enclave at Mount Athos was ideal for spending long hours performing such pious acts. Imiaslavie thus offered a flash of revelation for hundreds of monks fervently devoted to the arduous, all-consuming quest for personal salvation.

Invigorated in their faith, a band of Russian Athonites became embroiled in political turmoil while seeking to entrench their newfound ideals in monastic life. For months, they propagated Ilarion’s book and the power of the Name of God. Then, in January 1913, Antonii Bulatovich, a monk and former guard officer in the Tsarist army, led the removal of the Hegumen overseeing Andreevskii skit for not accepting imiaslavie as a valid Orthodox teaching. Bulatovich’s opponents cast this act as a purely political maneuver, labeling the change in leadership a “rebellion.” But Bulatovich retorted that Athonite monks had every right to depose a Hegumen deemed unfit for office and underscored the popularity of the measure, which had passed by a 302–70 vote.

In spite of these justifications, alarm spread rapidly through the myriad ecclesiastical and governmental authorities linked to Russian Athonite monks. Initially, neighboring monasteries attempted to quell the unrest, insisting that Bulatovich and his men stand down. A small contingent of Greek soldiers even surrounded Andreevskii skit. Following appeals from both Bulatovich and his opponents, Ecumenical Patriarch of Constantinople Joachim III, whose ecclesiastical jurisdiction technically included the mostly autonomous Athonite peninsula, issued a memorandum prohibiting Ilarion’s book on Athos and castigating the imiaslavtsy for their “false teaching.” Still, the movement’s proponents soldiered on for months, defending the legitimacy of their theological interpretations and their jurisdiction over their corner of Mount Athos.

Meanwhile, this prolonged controversy publicly undermined Russian authorities’ efforts to project themselves as political and religious leaders of the Orthodox Ecumene. Concerned that no other responsible actors would adequately intervene, the Russian government sent its navy to put a decisive end to the matter. On July 5, 1913, sailors from three warships raided Athos, arresting and deporting over 600 Russian monks—an act of questionable legality. Russia had no legal authority over Athos, most of which was in Greek hands throughout the First and Second Balkan Wars (1912-1913), nor over the resident Athonite monks, who had long aligned their citizenship with the government controlling the peninsula (e.g., the Ottoman Empire until 1912). In the end, might proved right, as the deportees’ objections to these violations of international law failed to draw any practical opposition to Russia’s show of force.

The pressing legal questions surrounding the imiaslavtsy were only exacerbated by their arrival in Russia. Having deported the monks by force, the state left the task of persecuting them to the Holy Synod, the council governing church affairs in Russia. Lacking any analogous precedent, the Synod formed an ecclesiastical court in Moscow in spring 1914 to try 25 “leaders” of the “rebellion.” The accused refused to recognize the court’s legitimacy, with some even calling for an all-Russia gathering (sobor) in which they might conceivably attain popular support. Despite their outspokenness, the monks were only lightly reprimanded for propagating “false teaching” and even permitted to retain their monastic titles and remain in communion with the Church. Notably, however, the Synod strictly forbade all deportees from returning to Athos. Meanwhile, the other 600-odd imiaslavtsy existed in a liminal space through 1917, never being assigned to a trial that would clarify their formal relationship with the Church and Orthodox community. Although the urgency of the First World War likely contributed to this ambiguous approach toward the imiaslavtsy, the state and Synod’s patronizing view of these monks as uneducated laymen unfit to plumb deep theological matters probably also contributed to their fate.

The failure to fully resolve the imiaslavie controversy reaffirms the larger complexities facing the Orthodox faithful in the waning Russian Empire. Did laymen-turned-monks have a right to engage in theological debates? How could believers distinguish between “correct” paths to salvation and erroneous, heretical ones? Where did the boundaries separating state and ecclesiastical jurisdictions lie, and how did that division (or lack thereof) influence Russians’ personal rights? Grounded in fundamental conceptions of authority, “orthodoxy,” and the “religious” or “secular,” these questions underscore how further research into the imiaslavie movement could contribute to our understanding of Russian Church and political history.