We at the Jordan Center stand with all the people of Ukraine, Russia, and the rest of the world who oppose the Russian invasion of Ukraine. See our statement here.

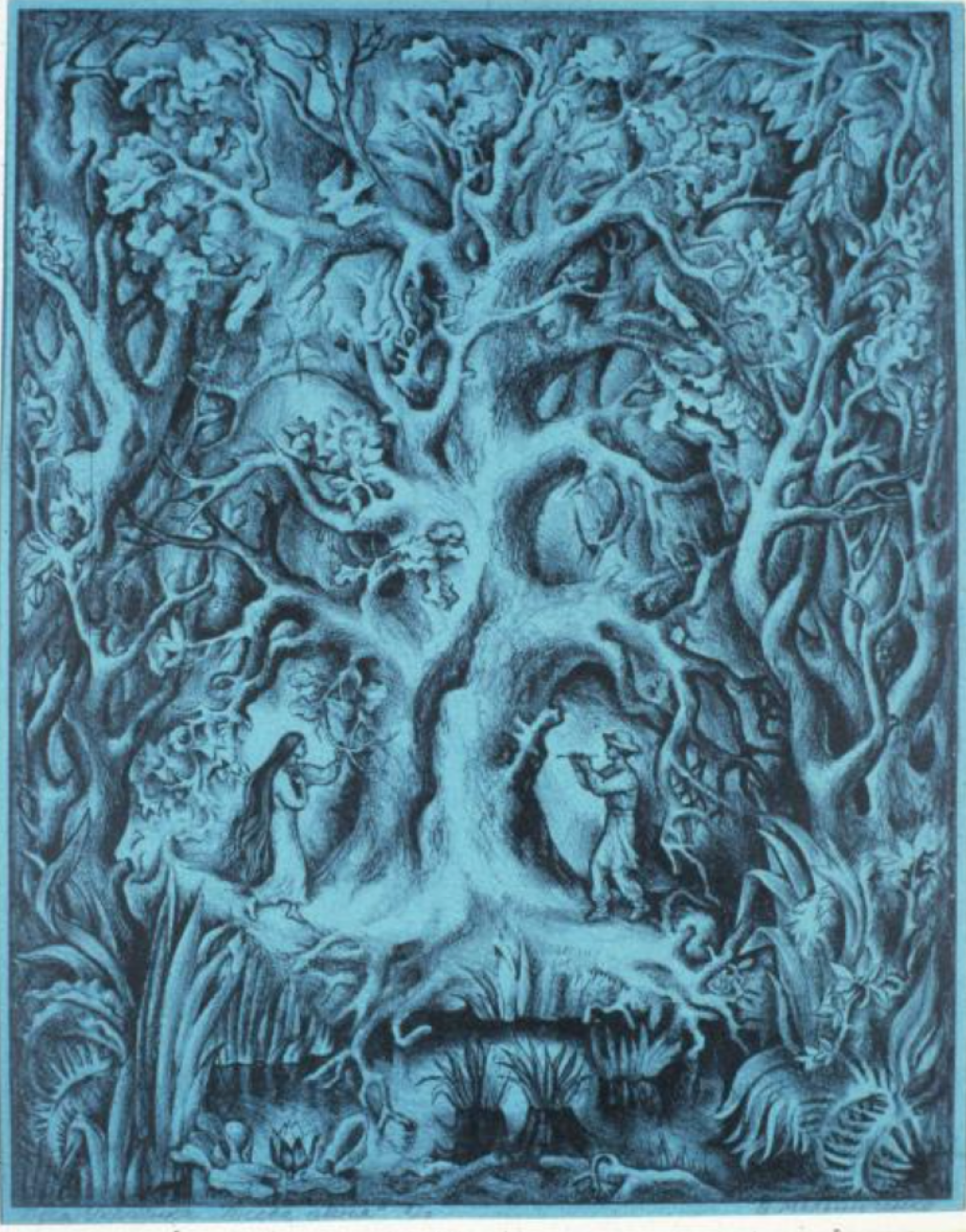

Above: An undated illustration of Lesia Ukrainka's Lisova Pisnia (Forest Song) by Valentina Mel'nichenko (born 1946). Source

Born and raised in Kyïv, Ukraine, Anastassiya Andrianova is an associate professor of English at North Dakota State University.

I concluded my recent ecofeminist analysis of Lesia Ukraïnka’s Lisova pisnia (Forest Song, 1911) by asking about the plight of nonhuman creatures in the Volyn' Polissia, where the modernist fairy-drama is set, at the time of Lesia Ukraïnka’s writing and today. Along with its film adaptations, Forest Song can be understood as an ecological parable that draws attention to the region’s history of deforestation and contemporary illegal amber mining, which is ravaging the landscape and reducing forest and agricultural land to bare soil. That “secret war” over fossilized tree resin involves miners, armed gangs, corrupt government officials, and tens of thousands of impoverished villagers. Rereading those concluding lines after Russia’s unprovoked invasion of Ukraine, I must now ask, what happens to nonhuman life disrupted and annihilated by war?

We keep seeing images of unhomed, displaced nonhuman animals in the media alongside their unhomed, displaced human companions, some fighting, others being evacuated. “Animals,” a photo collage in The Atlantic makes clear, “Can Be Refugees Too.” This pulls at all the heartstrings. As animal scholar Erica Fudge suggests, when it comes to interspecies empathy, “the truly meaningful animal is often a very individualized being.”

Indeed, when my parents fled war-torn Kyïv, they took their nearly 13-year old dachshund Tina, who now lives with my brother and his family, displaced internal refugees in Western Ukraine. But they also had to leave behind two other homeless mixed breeds, Mila and her daughter Frida, whom my mother and a host of local canine enthusiasts had cared for in their Kyïv district of Obolon'.

But reading Forest Song as an ecocritic, I become aware of the broader ramifications of this war on the ecosystems as a whole, particularly Ukraïnka’s beloved Polissia—now forcefully, unconscionably, inhumanely emptied of all life except for the Ukrainian territorial defense digging trenches or, like my parents, the refugees passing through on their way to safety.

Polissia, Ukraine’s forest belt and a geographic region encompassing approximately 100,000 square kilometers, includes most of the Volynia, Rivne, and Zhytomyr regions, and the northern part of Kyïv oblast'. All of these regions appear on maps of Ukraine tracking the Russian invasion.

Polissia is also a bioregion that defies and is not bound by human-drawn state or national borders. Part of Polissia lies north of Ukraine in Belarus. But instead of collaborating to curtail ecologically damaging practices, like amber extraction or berry harvesting that involves the building of illegal roads, littering, and vegetation trampling, the current focus is—as it should be—on Lukashenko’s mobilization of the Belarusian army against neighboring Ukraine.

Obviously, the Ukrainian army and territorial defense forces must do whatever they can to defeat the enemy. Cutting forest trees and digging trenches is a small price to pay, but it is an environmental loan that will eventually have to be repaid with high interest.

Familiar and dear to any Ukrainian, Lesia Ukraïnka’s Forest Song offers a valuable perspective on anthropogenic deforestation: Lukash, the male lead, makes sopilki (pipes) out of trees indigenous to Polissia and builds a hut in a habitat previously dominated by supernatural forest spirits, including Mavka, the forest nymph, whom he falls in love with and later abandons for a more proper human wife, Kylyna. Ultimately, the forest ecosystem revolts against the human invasion, the hut is set on fire, Mavka transforms into a willow, and Lukash dies.

Almost two months into Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, I can’t help imagining Lisovyk (the Forest Elf) as a soldier in a Ghillie suit, or the Ukrainian territorial defense blowing up bridges to prevent the Russian army from crossing—as “Toi, shcho hrebli rve” (He Who Rends the Dikes). The Russians’ ineffectively camouflaging their tanks with tree branches only furthers this analogy.

Ukrainian critic Petro Odarchenko has described the drama’s ending as “somber, deeply tragic.” From the perspective of environmental history, however, it is more promising. Traditional environmentalism’s assumption that natural habitats may be saved merely by excluding humans may be naïve and belie the fact that there is no such thing as a pristine “wilderness,” as such habitats have historically been shaped by humans and nonhumans alike. Yet, leaving those biomes alone, free of meddling humans, and giving time for trees and other lifeforms they house to regrow is probably the best eco-strategy we have.

This is not the strategy of Russian occupiers and their tanks. Ironically, it is possible that Russia’s war has paused amber extraction by eliminating access to the black market trade. But this may also mean that thousands of people in poorly industrialized areas have lost their only livelihood.

At the time when Viktor Ivchenko’s Lisova pisnia (1961) and Yurii Illienko’s Lisova pisnia. Mavka (1980), two Soviet Ukrainian film adaptations of Forest Song, were produced, environmental concerns were met largely with “indifference or ignorance, or both,” in the words of one historian. Although there was some discussion of environmental issues in the mass media, such as air pollution in the Baikal-Amur Mainline project following the 1973 decision to revitalize it, environmental degradation—like most social ills of the Soviet era—was mostly censored, kept secret, and distorted by official channels.

As Marko Pavlyshyn has demonstrated, in the 1960s, in the face of deteriorating landscapes and growing concerns over nuclear power, the USSR did witness “the emergence of a conservationist consciousness,” though less pronounced than in the West. Still, the fact that the publication of Oles' Honchar’s Sobor (The Cathedral, 1968) caused a literary scandal and the novel was subsequently excluded from standard reference works (until it was rehabilitated in 1986) confirms that few even prominent writers could openly critique industrial pollution.

Based on this history of prioritizing industrialization, downplaying environmental policy, and realizing the Marxist mythology of the “struggle with” and “conquest of” nature, I have argued that Ivchenko’s and Illienko’s films, whether deliberately or not, contributed to the nascent conservationist movement. The former did so by sentimentalizing Polissia in a saccharine melodrama, and the latter by (unfortunately) hypersexualizing a feminized nature in an otherwise bold, experimental take on Ukrainian “poetic cinema.”

Ukrainian literary and cultural studies can help direct public attention toward ecological devastation and call for environmental reform. As Inna Sukhenko has argued, the Soviet Union’s industrialization, along with the abuse of natural resources after the Second World War, “was an extreme threat to human life as well as a way of demolishing cultural memory.” Sukhenko finds that contemporary Ukraine has largely abandoned its “historically and ethnically rooted nature-oriented spirituality” for a more western, utilitarian, and “destructively materialist” attitude toward nature that privileges human interests. But how to reignite Slavic nature-centric beliefs and combat dualistic conceptions of humans and nature?

MAVKA. The Forest Song, a recent project also inspired by Lesia Ukraïnka’s celebrated drama in collaboration with the World Wildlife Fund—Ukraine, aims to raise ecological awareness about extinction and the loss of habitats. Its production having been repeatedly—and now likely indefinitely—postponed, it also means to promote Ukrainian music, folklore, and mythology. The project’s creators could not have possibly anticipated that Ukrainian culture, too, would come under attack and threat of extinction.

In a public forum on the war I participated in last month, a veteran in the audience asked why we should care about these deaths when life as we know it on our planet is doomed, given the global climate crisis. Setting aside its callousness, this is one of two most common responses to what philosopher Donna Haraway has described as “the horrors of the Anthropocene and the Capitalocene”: the one employs the apocalyptic trope, the other puts faith in some techno-fix.

I responded by pointing out that this war has made visible the pervasive and ultimately destructive ways in which central and western Europe, but also the rest of the world, is dependent on fossil fuels—specifically, on Russian oil that feeds Putin’s bloody war machine.

This is not the time to give in to techno-pessimism, nor over-rely on techno-optimism—though closing the sky is long overdue and those fighter jets are sorely needed! Also needed is the development of and financial incentivization for more sustainable green energies. When Russia’s war on Ukraine is over, Ukrainians and the world will have to confront that other “secret war.” The environmental nightmare facing Polissia and the nonhuman across Ukraine is, after all, another Soviet legacy that sovereign, independent Ukraine is more than capable of taking on.

Capitalist thinking focuses on the destruction of the environment as it relates to Ukraine as “the breadbasket of Europe,” noting ecological destruction in terms of lost (human) capital and the globally soaring price of wheat. Ecological thinking, by contrast, can be seen in the memorable video of the Ukrainian woman who gave the Russian soldier sunflower seeds, with the implication that his rotting corpse might become fertilizer for future sunflowers, Ukraine’s national flower. Restoring and reinhabiting ecologically damaged places will demand not just cleaning up waste and reintroducing plant- and wildlife, but also this sort of outside-the-box creativity.