Featured

Testing out “Friendship of the Peoples”: Soviet-Jewish Evacuees in Uzbekistan during the Second World War

My study of some 120 WWII-era Jewish evacuees to Uzbekistan sought to learn whether their experiences could be framed as a success of the Soviet doctrine of “friendship of the peoples.”

The Russian Economy Three Years after the Full-Scale Invasion of Ukraine

Since Russia began its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, its surprisingly strong economy has enabled the government to continuously replenish its military forces without implementing unpopular mass mobilization.

Excerpt from "After the Gulag: A History of Memory in Russia's Far North"

The Putin regime sees the archives Gulag survivors and their children have built as a threat because they lay bare Soviet crimes, juxtaposing these with the state-sponsored cult of the “Great Patriotic War.”

Was An Iconic Pushkin Heroine Actually a Woman of Color?

Some of Pushkin’s contemporaries associated Russian serfdom with American slavery—and hence, the poet’s youthful liberalism with his African ancestry.

Untangling Green Energy Contradictions in Central Asia

Kazakhstan and Uzbekistan are at the forefront of regional efforts in renewable energy investment, while also being the largest oil and gas-producing nations of Central Asia.

Was the Stalin Era’s Most Influential History Textbook an Imperial Narrative?

The Stalin-era "Short History of the USSR" subordinated both its critique and endorsement of empire to the celebration of state-building on either side of the revolutionary divide.

Our Hearts Pump in the Rhythm of Hope: The Student Uprising in Serbia

Since November 2024, massive student-led protests against government corruption have roiled Serbia, inspiring a nationwide movement demanding systemic change.

Internet and Public Trust in Government in Central Asia

In Central Asia, more Internet content creation—e.g., posting and blogging—is associated with higher trust in the government and a higher likelihood of election participation.

Blood Libel in Russian Imperial Georgia: The Kutaisi Trial, Part II

When the Jewish defendants in the 1879 Kutaisi trial were finally acquitted, the judges’ decision was met with sustained applause in the courtroom.

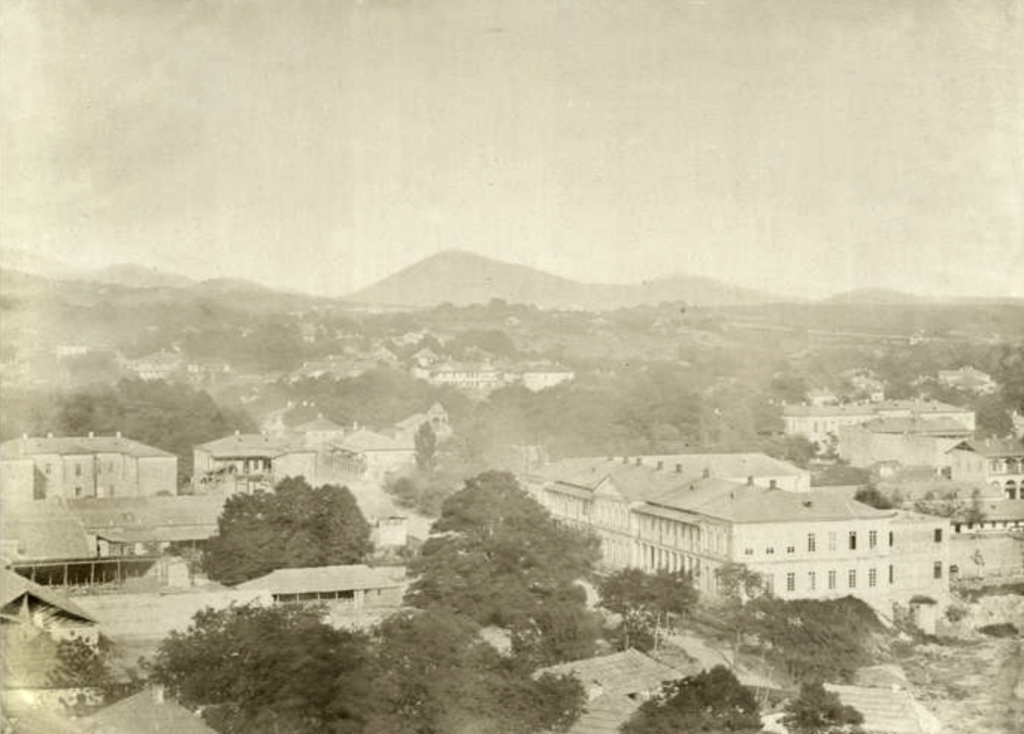

Blood Libel in Russian Imperial Georgia: The Kutaisi Trial, Part I

In March 1879, in the Georgian city of Kutaisi, then part of the Russian Empire, nine Jewish men stood trial for allegedly killing a Christian child.

Ethnic Pornography in the Balkans: National Identity Between Sex and Violence

Through four case studies from the former Yugoslavia and its cultural legacy, I interrogate both canonical and marginal forms of the ethnopornographic imaginary.

Recasting Security as High- and Green-Tech: China, Russia, and the Rare Earth Trade with the West

When it comes to Rare Earth Elements, China dominates the global supply, with Russia holding a strategic, though still secondary, niche.

Ukrainian Christmas traditions in Kazakhstan and Canada: Folklore, Folklorism, and Preserving Heritage

Folklore adapts to lived circumstances and living folk traditions are different from those of the past precisely because they are alive and suit their circumstances.

Is Post-Communism Over? What We Learned by Looking at the Data

Formerly communist countries have undergone such dramatic transformations since 1991 that it's unclear if "post-communism" remains a meaningful analytical category.

Moldova, the Latvian Purges, and Khrushchev’s Generational Struggle, 1958-1962

Khrushchev’s quiet attempts at replacing the older generation of Party leaders played out differently in two Soviet republics on the USSR's western borderlands.

The Boundaries of Religious Freedom: Transformation of State-Religion Relations in Azerbaijan

In post-Soviet Azerbaijan, the state has moved from religious neglect to active management of faith communities, balancing control over foreign influence with promotion of “traditional” religious expression.

Movement, Theory, Artistic Agency: Bronislava Nijinska's Revolutionary Dance Pedagogy in Post-Revolutionary Kyiv

In revolutionary Kyiv, Bronislava Nijinska's Ecole de Mouvement transformed dance education by uniting intellectual and physical training—creating artists, not just dancers.

Spirits of the Dead, Family Memory, and Resilience in the Indigenous Arctic

Despite various challenges, family legacy continues to be preserved and passed on, shaping animistic practices and concepts among the Asiatic Yupik people in the North-Eastern Russian Arctic.

Formerly Deported Peoples: A Search for Justice That Did Not Lead to Action

Some observers have predicted that Russia’s ethnic mosaic, and non-Russian peoples’ grievances, will drive the country’s future transformation. Recent history gives little reason to hope for such an outcome.

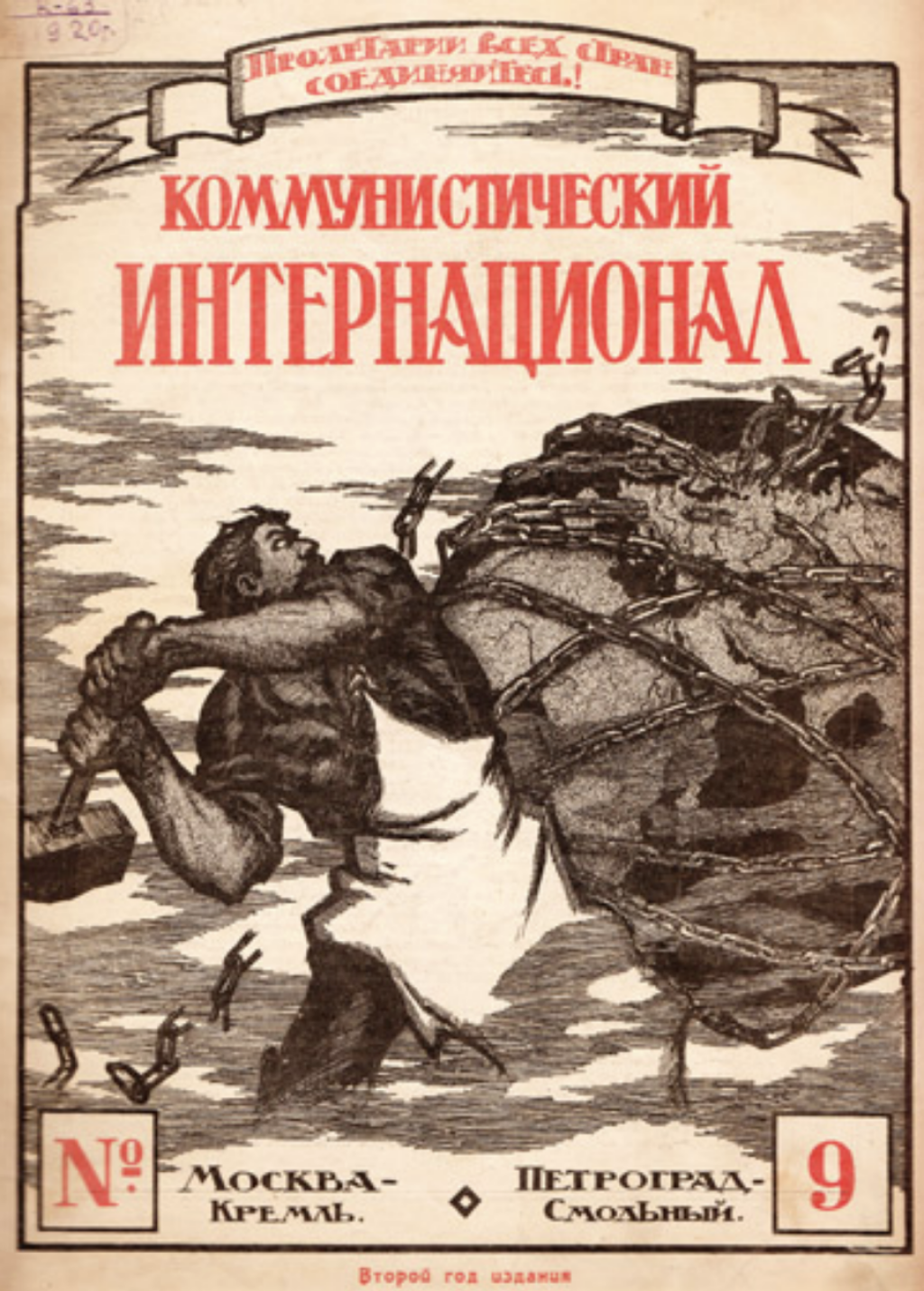

The Comintern and the National and Colonial Question: Reconsidering the Roots of Soviet Anti-Imperialism and Anti-Racism

Recent scholarship on the Comintern has expanded our knowledge of communism’s importance to anti-imperialism, decolonization, and racial equality movements in the interwar period. This scholarship has also explained the movement's limits.